By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 22 August 2023

Main categories: Development, Knowledge Management

Other tags: Activism, bani, design_thinking, ecosystems, Engagement, facilitation, foresight, framing, futures, naming, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, potfolio_based_approach, sensing, stakeholder_analysis, system_analysis theory_of_change, Use, vuca

No Comments »

In recent decades, the acronyms VUCA and, more recently, BANI have become popular to describe the environments in which we live and work. But, beyond describing the situation or environment as VUCA or BANI, can we do anything about it? How can we change our way of managing projects or promoting impactful public policies? We have compiled below a set of emerging methodologies that allow us to move from theory to practice, from fear to action.

Table of contents

New environments: VUCA & BANI

VUCA

VUCA appears with the end of the Cold War, with globalization, with the digital revolution, with the financialization of the Economy. Adapting theories on leadership from Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus, it proposes that we increasingly operate in environments:

- Volatile: the dynamics of change are accelerated and the stages of the situations are short-lived;

- Uncertain: it is increasingly difficult to predict the future (and science must adapt to post-normality);

- Complex: where the causal relationships of a phenomenon are multiple and even impossible to define;

- Ambiguous: since it is difficult to make categorical statements, especially independent of each different situation or context.

BANI

Impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, Jamais Cascio proposes in Facing the Age of Chaos to go beyond the definition of VUCA environments and suggests the BANI framework instead:

- Brittle: due to the extreme delicacy and contingency of situations, which can change quickly and drastically as a result of any cause;

- Anxious: in the sense that situations increasingly generate anxiety (due to the difficulty of dealing with them, due to the scope and depth of their impacts);

- Non-linear: due to the apparent disconnection, in direction and magnitude, between causes and consequences;

- Incomprehensible: since it is increasingly difficult to understand not only the causes but the very phenomena that we face.

Managing complexity for systemic impact

If the management of organizations, the fostering of public policies or the deployment of development (cooperation) projects follow one another in a practically deterministic way (if I do A, then B will happen) and a linearly way (few variables, always in a single direction), as environments grow in complexity, project management and impact public policies should also change.

With the management of complexity, new methodologies and approaches to management appear that incorporate three factors that were not always taken into account in traditional management, all of them related to the loss of control over the situation:

- Multifactoriality: realization and acknowledgement that there are many factors (particularly actors) that we do not control or even do not know, but that must be taken into account in the design as far as possible.

- Importance of design: since we cannot act arbitrarily or discretionally due to loss of control over factors, we try to control the playing field or, at the very least, to know it. Thus, the thoroughness on the design of the projects and the exhaustive knowledge of the environment are key.

- Influencing the system: although it may seem contradictory, since we are neither able to control nor often know the causal relationships, many projects will influence changing the system itself and will not limit themselves to operating within the system itself. The system becomes a dependent variable on which we can influence, not a variable that is given and to which we have to adjust.

Below we list some methodologies, approaches, concepts —with a more descriptive than normative goal— that incorporate new factors and perspectives to address the growing complexity in project management and public policies.

After each epigraph, a link “Some references on…” is added, which leads to a personal collection of documents that delve into the subject matter (on various occasions some documents are referenced in more than one epigraph when dealing with more than one topic).

Stakeholder analysis, naming, sensing, framing

The first major, necessary, incorporation of complexity is that of who, which actors intervene or are affected by an issue, a problem, a decision, a public policy. It does so through various names, each one with its particularities, the most common being the actor mapping and stakeholder analysis, but also interest groups and other denominations.

It is important to highlight that it is not only about making an inventory of actors, but also about how they read reality from their particular point of view. For instance, the question of housing has different readings and names depending on the actor: the problem of evictions, mortgages, rents, squatting, occupation mafias, immigration mafias, gentrification, tourist apartments, financial speculation, financialization of the economy, etc.

If we want to find solutions, we have to refine the diagnosis, and this involves incorporating all the different visions —without prejudices or moral judgments. How we “listen” to these actors —in Open Government we would speak of active listening— will be essential for the incorporation of all these visions.

Systems (systems analysis)

In the same way that it is done with actors, systems analysis tries to break down a complex problem into its basic components and processes, delimiting tasks, functions, relationships, direction of said relationships, etc.

Of course, systems analysis and stakeholder analysis are closely related, although while the latter is more focused on the subjects, the former is focused on their respective functions and interrelationships.

Systems analysis will provide better operational planning, improved ability to design and to implement better focused devices and assigning them the necessary resources (people, time, materials) to promote the components and functions that we want to leverage.

Foresight, futures

Foresight exercises are not new. “Foreseeing the future” —in the sense of considering what scenarios may occur in the future and with what probability— has been an exercise that humanity has carried out recurrently over the centuries.

However, the study of futures goes beyond mere prospective, for at least three reasons:

- For the abandonment of the hegemony of traditional statistics and the incorporation of post-normal science, which requires radical new approaches to the approach of what can happen and why.

- For to the incorporation of new actors and functions and the creation of new scenarios. In other words, and related to the previous points, it is not only a question of foreseeing what can happen, but of capturing what these future scenarios can be like, beyond whether they are possible and to what extent.

- For to the formation of new realities at the same time that we think about them, along the lines of what was previously commented on taking the system as an endogenous variable: futures exercises are often not only inventories of what can happen but also of what we would like to happen —and, as we will see later, what would have to be done to make them possible and probable.

Outcome mapping

Out of all the possible scenarios, outcome mapping helps us identify the effects we want to see happen. The concept of outcome is sometimes confusing and used interchangeably as effect or impact. Strictly speaking, in the activities we carry out, three stages of “impacts” can be distinguished:

- Output, result: the “thing” (good, service) that we have produced and that is under our control. E.g. a basic digital literacy course.

- Outcome, effect: the intermediate changes, in the short term, in which we have been able to influence directly. E.g. improve the ICT competence of some people.

- Impact, impact: structural changes (behaviors, visions of reality, etc.), in the long term in which we can influence indirectly but to which we ultimately aspire. E.g. improve the employability of a collective.

Outcome mapping focuses the analysis on those effects that we can influence and that are real changes in a situation. They force us to think (and design) for impact, for transformation, avoiding “solutions” whose results are an investment of resources without impact on the system.

Theory of Change

The Theory of Change is linked to outcome mapping and tries to find the causal relationships that lead to impact, what we can do to obtain a certain result or impact. The Theory of Change identifies the necessary resources to carry out activities that will have expected results controllable to a certain extent; and, based on these results, and the causal relationships inferred or found by experimentation, expect to be able to influence directly to achieve effects and, indirectly, to achieve results, impacts.

The Theory of Change, like any theory, must be validated and, for this, evaluated. In the Theory of Change, evaluation (measurement, verification, ratification or refutation) is fundamental and forms part of the various iterations of the implementation of the Theory of Change.

It is important to note that the Theory of Change, like the very definition of results, effects and impacts, is very circumstantial or contextual: there are intermediate effects that are impacts at another level of analysis and vice versa: impacts that, at another level, are mere results, that can lead to other higher impacts.

Portfolio-based approach

The portfolio-based approach is situated (conceptually) halfway between stakeholder analysis, systems analysis and the Theory of Change. If we admit that we do not have control over everything, and that we need to mobilize certain resources to achieve certain results, we need to know what assets we all have together and how we can align them to achieve a common goal.

Going back to the Open Government paradigm, it is about acknowledging, from this map of actors, how each one participates in the project, but not only with their vision, but also and above all, with their own contributions (materials, methodologies, etc.).

To some extent, the portfolio-based approach challenges the foundations of classical organizational theory: counting on resources that “are not yours.” But, with the appropriate strategy, they can be mobilized and aligned for the common objective. For this reason, this approach fits into the entire complexity management map, where actors, relationships, scenarios and causal relationships have an architecture that is so different from classical management by processes.

Participation, facilitation, design thinking

Faced with this great organizational complexity, how we implement it comes to the forefront, even coming before the planning itself, at least the operational one.

The participation of the actors in the processes of diagnosis, deliberation, negotiation, decision-making or evaluation becomes essential; and the facilitation and revitalization of these participation processes to achieve the objectives, so that participation is efficient and effective. Of course, the logic with which it is created (or co-created, and later co-managed) requires new design methodologies: design-thinking , agile methodologies and others are now incorporated into the toolbox to enhance it.

Ecosystems

Recently the concept of ecosystem has jumped from the realm of biology to that of technology, and from there to that of the social sciences. In a first meaning outside the field of life sciences, we speak of the ecosystem approach characterized by global vision, comprehensive action. It is a first meaning, but when we talk about governance ecosystems (of projects, of policies), the concept goes much further —going beyond what, in fact, could be assimilated to the vision of the system that we saw previously.

When we talk about acting with an ecosystem approach, we admit that its complexity often does not allow direct action. We saw it when talking about the multiplicity of actors, their relationships, their respective portfolios, how they co-design actions or align themselves with them, the multiplicity of scenarios and desirable results and impacts, the difficulty of establishing relationships causes over which we have no control (only influence, often indirectly). Given this scenario, the ecosystem vision is characterized, in addition to the global vision and comprehensive action, by:

- Act on the environment, on the context, to influence (indirectly) the results, effects and impacts. This is done by providing the generic infrastructure of the ecosystem.

- Promote the autonomy of the actors, providing transversal applications (methodologies, instruments, resources, codes, standards) that they can use freely.

- Align the different autonomous instances (projects, institutions) of the actors through the design of the infrastructure and transversal applications, promptly providing incentives that reward alignment or penalize (or leave rewardless) divergence.

The ecosystem vision, therefore, promotes the project or the institution as a platform on which others operate, where institutions and projects become open infrastructures for autonomous decision-making with collective impact.

In conclusion, the way of approaching projects, the management of organizations or the promotion of public policies is changing radically as a result of the verification of the profound (and constant and accelerated) transformation of the contexts and environments in which these take place. and they operate.

There is no single model, and often the methodological proposals are heterogeneous, from what are mere descriptions to highly complex organizational and operating architectures. However, all of them seek to overcome a way of designing and managing that shows many signs of fatigue, insufficiency, and inefficiency. For now —and, perhaps, for a long time— it will be necessary to arm ourselves with a new toolbox, profiles and skills to perform new tasks and tackle new challenges and try to provide solutions, always incomplete, always tentative, always temporary, but always also necessary to influence the environment, in the context, to, through these, progress.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 13 February 2018

Main categories: Knowledge Management

Other tags: chief_research_officer, consultancy, cro

No Comments »

It is not unusual to hear that the university and consultancy firms go opposite ways: for the former, spending too much time in knowledge transfer has huge costs of opportunity, for it is time not invested on publishing in impact scientific journals; for the latter, most research just cannot be easily included in the client’s bill.

What follows is just a simple exercise on how to embed research in consultancy, so that it does not become a mere overhead but an activity that has a direct measurable impact on the value chain. The scheme presents to sets (columns) of tasks that a chief research officer —or a research office, intelligence unit or knowledge management team, etc.— can perform within a consultancy firm. On the left, we have drawn the tasks that impact the internal client and thus improve others’ activities; on the right, we have drawn the tasks that can by directly put in the market as a product or a service.

The Chief Research Officer in consultancy firms

The Chief Research Officer in consultancy firmsActivities have been grouped in five (more or less chronological) stages:

- Research: which stands for more basic or less applied research, and consisting in gathering information, building theoretical models and providing strategic advice to the firm. On a more public branch, it can consist on creating measuring devices such as indices or custom measurements, sometimes commercialised as ad-hoc audits.

- Branding: part of research is diffusion. Conveniently tailored, it can contribute to strengthen the power of a brand, contribute to create a top-of-mind brand or even, by lobbying and media placing, to have an impact in the public agenda.

- Consulting: the research office can work with the consulting team in some projects (especially at the first and last stages of the project) to improve its quality. Mind the (*) in consulting, meaning that the research office should not work as a consulting team: research and analysis does require some distance from the research object and, most important, different (slower) tempos than regular consulting activities have.

- Training: a research office that learns should teach, both to other departments of the firm or directly as a service to the clients. Providing policy advice or openly publishing position and policy papers is another way to transfer knowledge to specific clients or openly to society.

- Innovation: closing the virtuous circle of research, modelling and improving methodologies is a way to capitalise the investment that the firm made in a research office, thus making it more efficient and effective.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 May 2016

Main categories: Knowledge Management, News, Writings

Other tags: EAFT, proceedings

No Comments »

The European Association for Terminology has just published the Proceedings of the VII EAFT Terminology Summit 2014: Social Media and Terminology work

in which I opened with a keynote speech: The challenge of being (professionally) connected.

The topic dealt with the fact that being up-to-date with digital technologies (ICTs in general, social media in particular) is not a luxury but a must for people working in knowledge intensive environments or jobs. And, beyond the uptake of digital technologies, there is also the need to build networks around one-self — not necessarily digital ones, but surely enhanced and often enabled by digital technologies.

Please find below the slides and (subsequent) full text of the conference.

Abstract

Throughout the history of humankind, information has been trapped in a physical medium. Cuneiform tablets in Mesopotamia, papyrus of ancient Egypt, modern books, newspapers. Even the most intangible information, the one locked inside the brains of people, usually implied having to coincide in time and space with the device that contained what we wanted to know. That’s why, for centuries, we have structured our information management around silos – archives, libraries, collections, gatherings of experts – and around ways to structure this information – catalogues, taxonomies, ontologies. The information lives in and out of the well, there’s the void. With the digitization of information, humankind achieves two milestones: firstly, to separate the content of the container; secondly, that the costs of the entire cycle of information management collapse and virtually anyone can audit, classify, store, create, and disseminate information. The dynamics of information are subverted. Information does not anymore live in a well: it is a river. And a wide and fast-flowing one. Are we still going to fetch water with a bucket and pulley, or should we be looking for new tools?

Slides

Dowloads

Text of keynote:

Peña-López, I. (2016). “

The challenge of being (professionally) connected”. In European Association for Terminology (Ed.),

Proceedings of the VII EAFT Terminology Summit 2014: Social Media and Terminology work, 11-28. Barcelona 27-28 November 2014. Barcelona: EAFT.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 13 March 2015

Main categories: Knowledge Management, Open Access

Other tags: digital_scholarsip, e-research, e-science, enhanced_research, open_research

2 Comments »

For the last 10 years I have been developing my own strategy for open enhanced research — you can also call it e-research, research 2.0, science 2.0, or even digital scholarship. What follows is a simplification of the pathway that can be walked since one has an idea for a research topic/project until outcomes come up and end up in conclusions… conclusions that should feed one’s next research idea. And so on.

And how can the so-called tools of the web 2.0, social media contribute to open up research, to find kindred souls, to test your thoughts and ideas by sheer exposure, to bridge the ivory tower with citizens’ lives… and to be somewhat accountable to taxpayers if you are in a public institution.

It is by no means an exhaustive map of all that can be done in research, the web 2.0 and social media, and the tools and services here presented are just mere suggestions or indications where to begin with. It should be taken as what it is, a simple pathway, not even a roadmap.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 17 July 2014

Main categories: Education & e-Learning, Knowledge Management

Other tags: ple

4 Comments »

Working in the field of open social innovation, and most especially when one considers institutions as platforms for civic engagement, it is almost unavoidable to think of the personal learning environment (PLE) as a useful tool for conceptualising or even managing a project, especially a knowledge-intensive one.

Let the definition of a PLE be a set of conscious strategies to use technological tools to gain access to the knowledge contained in objects and people and, through that, achieve specific learning goals

. And let us assume that a knowledge-intensive project aims at achieving a higher knowledge threshold. That is, learning.

The common — and traditional — approach to such projects can be, in my opinion, simplified as follows:

- Extraction of information and knowledge from the environment.

- Management and transformation of information and knowledge to add value.

- Dissemination, outreach and knowledge transmission.

These stages usually happen sequentially and on a much independent way one from another. They even usually have different departments behind.

This is perfectly valid in a world where tasks associated to information and communication are costly, and take time and (physical) space. Much of this is not true. Any more. Costs have dropped down, physical space is almost irrelevant and many barriers associated with time have just disappeared. What before was a straight line — extract, manage, disseminate — is now a circle… or a long sequence of iterations around the same circle and variations of it.

I wonder whether it makes sense to treat knowledge-intensive projects as yet another node within a network of actors and objects working in the same field. As a node, the project can both be an object — embedding an information or knowledge you can (re)use — or the reification of the actors whose work or knowledge it is embedding — and, thus, actors you can get in touch trough the project.

A good representation of a project as a node is to think of it in terms of a personal learning environment, hence a project-centered personal learning environment (maybe project knowledge environment would be a better term, but it gets too much apart from the idea of the PLE as most people understands and “sees” it).

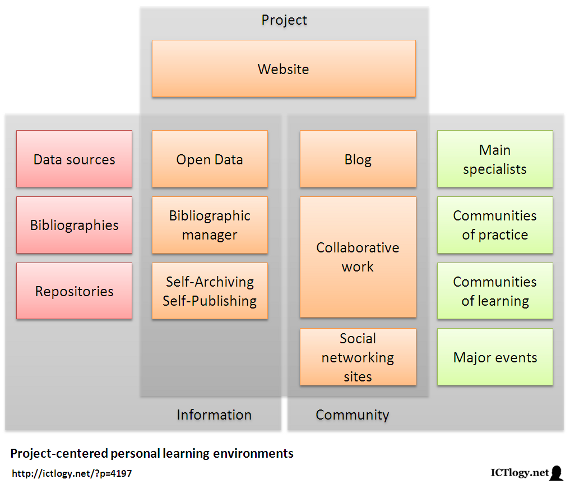

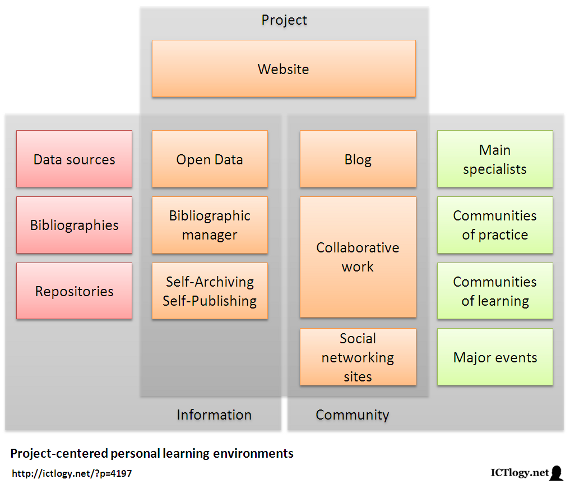

A very rough, simple scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment could look like this:

Scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment

Scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment

[Click to enlarge]In this scheme there are three main areas:

- The institutional side of the project, which includes all the data gathered, the references used, the output (papers, presentations, etc.), a blog with news and updates, collaborative work spaces (e.g. shared documents) and all what happens on social networking sites.

- The inflow of information, that is data sources, collections of references and other works hosted in repositories in general.

- The exchange of communications with the community of interest, be it individual specialists, communities of learning or practice, and major events.

These areas, though, and unlike traditional project management, interact intensively with each other, sharing forth information, providing feedback, sometimes converging. The project itself is redefined by these interactions, as are the adjacent nodes of the network.

I can think at least of three types of knowledge-intensive projects where a project-centered personal learning environment approach makes a lot of sense to me:

- Advocacy.

- Research.

- Open social innovation (includes political participation and civic engagement).

In all these types of project knowledge is central, as is the dialogue between the project and the actors and resources in the environment. Thinking of knowledge-intensives projects not in terms of extract-manage-disseminate but in terms of (personal) learning environments, taking into account the pervasive permeability of knowledge that happens in a tight network is, to me, an advancement. And it helps in better designing the project, the intake of information and the return that will most presumably feed back the project itself.

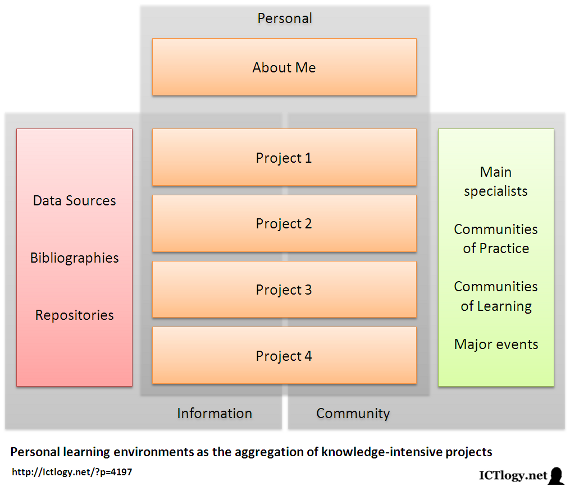

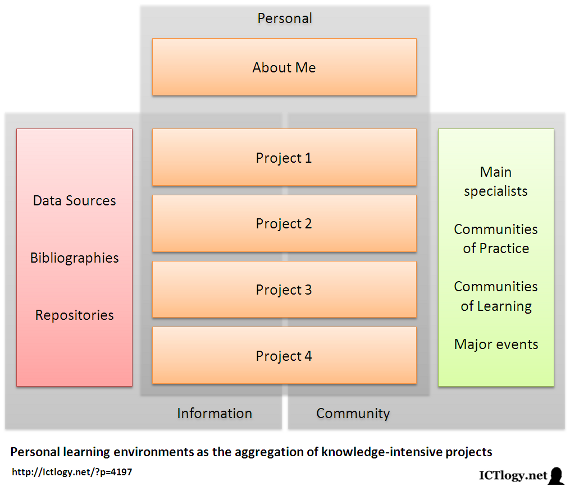

There is a last reflection to be made. It is sometime difficult to draw or even to recognize one’s own personal learning environment: we are too used to work in projects to realize our ecosystem, we are so much project-based that we forget about the environment. Thinking on projects as personal learning environments helps in that exercise: the aggregation of them all should contribute in realizing:

- What is the set of sources of data, bibliographies and repositories we use as a whole as the input of our projects.

- What is the set of specialists, communities of practice and learning, and major events with which we usually interact, most of the times bringing with us the outputs of our projects.

Scheme of a personal learning environments as the aggregation of knowledge-intensive projects

Scheme of a personal learning environments as the aggregation of knowledge-intensive projects

[Click to enlarge]Summing up, conceiving projects as personal learning environments in advocacy, e-research and open innovation can help both in a more comprehensive design of these projects as in a better acknowledgement of our own personal learning environment. And, with this, to help in defining a better learning strategy, better goal-setting, better identification of people and objects (resources) and to improve the toolbox that we will be using in the whole process. And back to the beginning.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 31 December 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, ICT4D, Information Society, Knowledge Management, Open Access, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: open_innovation, open_social_innovation, social_innovation

2 Comments »

Innovation, open innovation, social innovation… is there such a thing as open social innovation? Is there innovation in the field of civic action that is open, that shares protocols and processes and, above all, outcomes? Or, better indeed, is there a collectively created innovative social action whose outcomes are aimed at collective appropriation?

Innovation

It seems unavoidable, when speaking about innovation, to quote Joseph A. Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy:

The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.

In the aforementioned work and in Business Cycles: a Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process he stated that innovation necessarily had to end up with existing processes, and that entire enterprises and industries would be destroyed with the coming of new ways of doing things, as the side effect of innovation. This creative destruction would come from, at least, the following fronts:

- A new good or service in the market (e.g. tablets vs. PCs).

- A new method of production or distribution of already existing goods and services (e.g. music streaming vs. CDs).

- Opening new markets (e.g. smartphones for elderly non-users).

- Accessing new sources of raw materials (e.g. fracking).

- The creation of a new monopoly or the destruction of an existing one (e.g. Google search engine)

Social innovation

Social innovation is usually described as innovative practices that strengthen civil society. Being this a very broad definition, I personally like how Ethan Zuckerman described social innovation in the Network Society. According to his innovation model:

- Innovation comes from constraint.

- Innovation fights culture.

- Innovation does embrace market mechanisms.

- Innovation builds upon existing platforms.

- Innovation comes from close observation of the target environment.

- Innovation focuses more on what you have more that what you lack.

- Innovation is based on a “infrastructure begets infrastructure” basis.

His model comes from a technological approach — and thus maybe has a certain bias towards the culture of engineering — but it does explain very well how many social innovations in the field of civil rights have been working lately (e.g. the Spanish Indignados movement).

Open innovation

The best way to define open innovation is after Henry W. Chesbrough’s Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating And Profiting from Technology, which can be summarized as follows:

| Closed Innovation Principles |

Open Innovation Principles |

| The smart people in the field work for us. |

Not all the smart people in the field work for us. We need to work with smart people inside and outside the company. |

| To profit from R&D, we must discover it, develop it, and ship it ourselves. |

External R&D can create significant value: internal R&D is needed to claim some portion of that value. |

| If we discover it ourselves, we will get it to the market first. |

We don’t have to originate the research to profit from it. |

| If we create the most and the best ideas in the industry, we will win. |

If we make the best use of internal and external ideas, we will win. |

| We should control our IP, so that our competitors don’t profit from our ideas. |

We should profit from others’ use of our IP, and we should buy others’ IP whenever it advances our business model. |

Open Social Innovation

The question is, can we try and find a way to mix all the former approaches? Especially, can we speak about how to have social innovation being open?

In my opinion, there is an important difference between social innovation and innovation that happens in the for-profit environment:

- The first one, and more obvious, is that while the former one has to somehow capture and capitalize the benefits of innovation, the second one is sort of straightforward: if the innovation exists, then society can “automatically” appropriate it.

- The second one is the real cornerstone: while (usually) the important thing in (for-profit) open innovation is the outcome, in social innovation it (usually) is more important the process followed to achieve a goal rather than achieving the goal itself.

Thus, in this train of thought, open social innovation is the creative destruction that aims at making up new processes that can be appropriated by the whole of civil society. I think there are increasingly interesting examples of open social innovation in the field of social movements, of e-participation and e-democracy, the digital commons, P2P practices, hacktivism and artivism, etc.

I think that open social innovation has three main characteristics that can be fostered by three main actions of policies.

Characteristics

- Decentralization. Open social innovation allows proactive participation, and not only directed participation. For this to happen, content has to be separated from the container, or tasks be detached from institutions.

- Individualization. Open social innovation allows individual participation, especially at the origin of innovation. This does not mean that collective innovation is bad or avoided, but just that individuals have much flexibility o start on their own. This is only possible with the atomization of processes and responsibilities, thus enabling maximum granularity of tasks and total separation of roles.

- Casual participation. Open social innovation allows participation to be casual, just in time, and not necessarily for a log period of time or on a regular basis. This is only possible by lowering the costs of participation, including lowering transaction costs thus enabling that multiple actors can join innovative approaches.

Policies

How do we foster decentralization-individualization-casual participation? how do we separate content from the container? how do we atomize processes, enable granularity? how do we lower costs of participation and transaction costs?

- Provide context. The first thing an actor can do to foster open social innovation is to provide a major understanding of what is the environment like, what is the framework, what are the global trends that affect collective action.

- Facilitate a platform. It is not about creating a platform, it is not about gathering people around our initiative. It deals about identifying an agora, a network and making it work. Sometimes it will be an actual platform, sometimes it will be about finding out an existing one and contributing to its development, sometimes about attracting people to these places, sometimes about making people meet.

- Fuel interaction. Build it and they will come? Not at all. Interaction has to be boosted, but without interferences so not to dampen distributed, decentralized leadership. Content usually is king in this field. But not any content, but filtered, grounded, contextualized and hyperlinked content.

Some last thoughts

Let us now think about the role of some nonprofits, political parties, labour unions, governments, associations, mass media, universities and schools.

It has quite often been said that most of these institutions — if not all — will perish with the change of paradigm towards a Networked or Knowledge Society. I actually believe that all of them will radically change and will be very different from what we now understand by these institutions. Disappear?

While I think there is less and less room for universities and schools to “educate”, I believe that the horizon that is now opening for them to “enable and foster learning” is tremendously huge. Thus, I see educational institutions having a very important role as context builders, platform facilitators and interaction fuellers. It’s called learning to learn.

What for democratic institutions? I cannot see a bright future in leading and providing brilliant solutions for everyone’s problems. But I would definitely like to see them having a very important role as context builders, platform facilitators and interaction fuellers. It’s called open government.

Same for nonprofits of all purposes. Rather than solving problems, I totally see them as empowering people and helping them to go beyond empowerment and achieve total governance of their persons and institutions, through socioeconomic development and objective choice, value change and emancipative values, and democratization and freedom rights.

This is, actually, the turn that I would be expecting in the following years in most public and not-for-profit institutions. They will probably become mostly useless with their current organizational design, but they can definitely play a major role in society if they shift towards open social innovation.