By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 23 April 2009

Main categories: Development, Digital Divide, ICT4D

Other tags: wdi, world_bank

1 Comment »

(continued from World Development Indicators 2009: a commentary (part I))

The services are still unaffordable for many people in low-income economies, leaving them yet to realize the potential of ICT for economic and social development

This is quite evident by most data available, so my comment will be headed not on the fact of the digital divide, but on affordability itself.

According to my own research (again, more to come soon), after analysing 55 models that depict digital development and include more than 1,500 indicators, if we let aside the analogue indicators (e.g. GNP), 37% of the digital indicators were depicting the state of infrastructures, of which only one sixth were measuring affordability.

The rationale behind this argument is that not only most people cannot afford ICTs, but, according to what we measure, we can infer that most measuring tools — which are normally built to measure the impact of policies and strategies and projects — simply do not care or care little about affordability. If people cannot afford ICTs and policy-makers and decision-takers (amongst them development institutions) do not care about affordability, we’ve got a problem. A big one.

In developing economies innovative use of ICT services is changing people’s lives and providing new opportunities

Not that I disagree with this statement — have I already cited the Economic Benefits of ICTs? — but there is a shade of meaning to be made here. I increasingly think that ICTs are not a driver of inclusion but a driver of exclusion. In other words, people have to move (or develop digitally) to remain in the same place. ICTs actually do not create new opportunities, but the absence of ICTs or digital illiteracy do decrease the number of opportunities available to those on the wrong side of the digital divide.

See, for instance, the next figure that I presented — among other places — in my speech Digital students, analogue institutions, teachers in extinction and that is based on Manuel Castells’ Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society and Informationalism, Networks, And The Network Society: A Theoretical Blueprint:

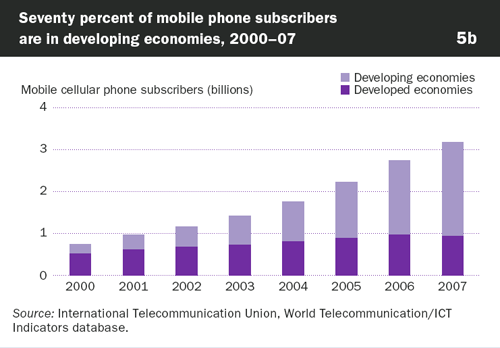

Mobile phones have captured the market in developing economies […] Seventy percent of mobile phone subscribers are in developing economies

The first part of this statement is absolutely true and people in developing countries — citizens or development agencies working in the terrain — know it perfectly. See, for instance, Mobile Web for Development or Innovative Uses of Mobile ICTs for Development.

But the second part is definitely misleading, as the next chart is:

Stating that 70% of the total mobile phone subscribers are in developing economies says little about the relative weight of such penetration. According to the World Bank itself, there are 6 billion people alive today: One billion people live in developed countries [while] the other 5 billion live in developing countries

. Which is to say: 83.3% people live in developing countries. Compared with 70% of total cellphone subscribers, there still is a gap of 13.3% in favour of developed countries. And if we take into account international agencies, development organizations and tourists (…and troops) — that buy domestic SIM cards to have local prices — the unbalance is even worst.

I am not saying that news are bad — which are not —, but that they are not as good as they might seem at first sight.

More information

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 23 April 2009

Main categories: Development, Digital Divide, ICT4D

Other tags: wdi, world_bank

No Comments »

The World Bank has published the World Development Indicators 2009. The indicators and the report that accompanies the updated version of the indicators are, arguably, one of the best comprehensive snapshots on the state of the question of development worldwide.

Concerning Information and Communication Technologies, the report devotes 5 pages to comment the subject (see chapter 5, States and Markets, pp.265-269,  92.5 KB). The main statements of this section are as the following, which I’ll be commenting one by one.

92.5 KB). The main statements of this section are as the following, which I’ll be commenting one by one.

ICTs used in e-government projects can reduce corruption

This is a statement I fully agree with. I already wrote about this in my article entitled The end of paper, open gates to on-time democracy (not about journalism) and there is plenty more evidence about what ICTs can do for transparency, accountability, democracy and human rights; and and efficiency and efficacy in the provision of public services.

Some ICTs, such as broadband, can contribute to economic growth

Again, see Economic Benefits of ICTs.

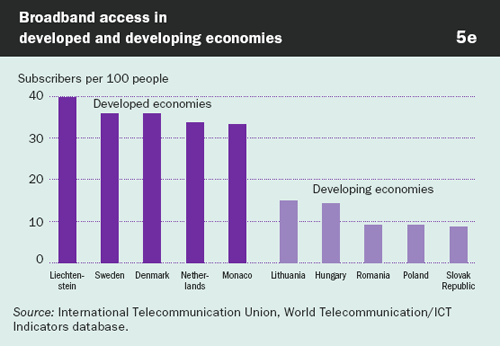

We must not, nevertheless, forget how broadband is unevenly adopted in the world:

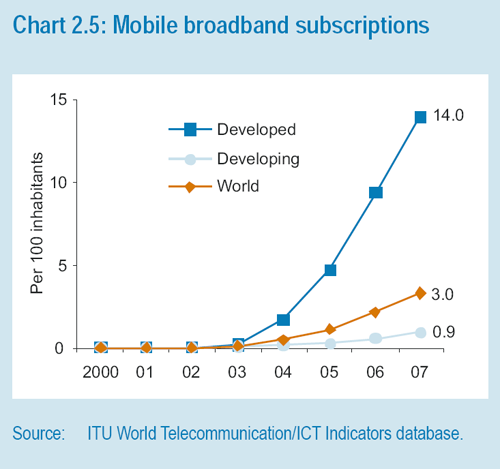

The problem is not, actually, that broadband distribution is unbalanced, but that the trend seems to reinforce this fact. As the International Telecommunication Union report Measuring the Information Society – The ICT Development Index 2009 shows, the broadband divide in the World has increased and the irruption of the mobile broadband has only worsened this unequality:

Good government policies and regulations are creating competitive ICT markets, increasing access to ICT services for people everywhere […] Many countries that have created a competitive market environment for ICTs have more people using ICT services

This is, to my understanding, where long term and broad impact ICT4D strategies should be headed. Thus, there is an urgent need to change the socioeconomic and political frameworks regarding ICTs and the Information Society in general.

My own research shows (more about this soon) that the role of the government has a huge impact in the probability (that is: it is a cause) of achieving higher levels of digital development. To be more specific, the following aspects highly determine digital development several orders of magnitude higher than other issues:

The well known success of mobile telephony worldwide has been achieved through high demand, low-cost technologies, and market liberalization

Complementary to what has already been said, macro-level policies have to be accompanied by grassroots and micro-level strategies and projects. The first one that comes to my mind is the — in my opinion — successful FrontlineSMS:Medic, building on the acknowledged flagship of SMS for development projects Frontline SMS. In a recent — and most insightful — talk I had with the promoter of Kiwanja, Ken Banks, we both agreed that “scalability” in the developing world might not mean the same thing as in developed countries, which follow market-led rules, but could be closer to the concept of “copy-and-spread”. In his own words in Time to eat our own dog food?: we need to think about low-end, simple, appropriate mobile technology solutions which are easy to obtain, affordable, require as little technical expertise as possible, and are easy to copy and replicate

.

(continues in World Development Indicators 2009: a commentary (part II))

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 15 April 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, Meetings

Other tags: Cristóbal_Cobo

1 Comment »

Live notes at the research seminar by Cristóbal Cobo entitled e-competence in the European Framework: 21st century literacies and based in his research Strategies to promote the development of e-competences. How to reduce the gap between the e-skilled and the non e-skilled?. Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Barcelona, Spain, April 15th, 2009.

How to reduce the gap between the e-skilled and the non e-skilled?

Research questions:

- Why does the Knowledge Society requires highly qualified labour force?

- How effective have the IT & education initiatives been?

- What means e-competence?

- How should the coming labour force be trained?

Why does the Knowledge Society requires highly qualified labour force?

In the last years, complex communications and expert thinking have been increasing in the share of tasks performed by workers, while PCs increasingly do the tasks that consist of rutine.

The World Bank’s Knowledge Economy Index is an appropriate framework to measure this shift towards more qualification in labour demand.

This shift has implied a huge gap between what is being taught at schools and what is being needed — and will be needed in the next generation of professionals — in the labour market.

How effective have the IT & education initiatives been?

And though there are plans (e.g. in Europe or the OECD) to foster and assess these needed skills, the implementation is not straightforward.

The European Commission has established three levels of ICT skills:

- Access to ICT

- Basic ICT Skills

- Advanced Use of ICT (Participation+Transaction)

But there is a physical digital divide, a growing demand of e-skills unmatched by a declining supply, a gender gap, half the population are non-users of the Internet…

Who needs digital literacy: age gap, gender gap, education gap, location gap, employment gap. Not new, but strengthened. Indeed, most non-users are due to lack of skills or e-awareness.

Still, self-learning still is the most relevant option when acquiring digital skills. Maybe policies should focus informal training instead of formal training.

Some issues in European assessments:

- The majority of teachers in most advanced countries (Dk. Se. Fi. Ne)* use ICT in less than 5% of their classes

- Students using PC more frequently at school do not perform better than others.Highest performances: students with a mediumlevel of computer use

- Impact of ICT on students’ performance was highly dependent on teaching approaches

- No correlation: ICT access & Øof teachers having used ICT in their teaching.No correlation: Levels of ICT use & levels of perceived learning gains from ICT use

- No clear advances (last decade) that can be confidently attributed to broader access to PC.

- Most educators use technology @ school for administrative tasks (fewer for class)

- The positive impact of ICT use in education has not been proved

BUT, the reason could be that computers/Internet are just used in old ways of teaching, reinforcing old methodologies, instead of focusing on educative innovation and applying them in new ways of teaching.

What means e-competence?

e-competence: Capabilities and skills to manage tacit and explicit knowledge, as well as to use digital technologies in a knowledge-based economy. There are several ways in which this general concept is put into practice or defined in deeper detail: the European e-competence framework, OECD, the ECDL by the Council of European Professional Informatics Societies.

Five stages of e-competence:

- e-Awareness: understanding the framework

- Technological Literacy: confident and critical operation of ICT

- Informational Literacy: read with meaning

- Digital Literacy: integration of instrumental and strategical skills.

- Media Literacy: understanding how traditional mass media and digital media are merging

How should the coming labour force be trained?

- Long Term Agenda and dialogue between education and business sectors

- e-Inclusion: forget the “ideal knowledge worker” but focus in potential excluded. Try to reach e-awareness, beyond just basic digital literacy.

- Standardization: set standards for ICT competencies: definitions, assessment, certifications… Standardization for the mobility of the workforce.

- e-Awareness

- Pedagogical Shift: avoid reductionist approaches

- e-Skills Teachers: impact of ICT on students are highly dependent on the teaching approaches, their skills and incentives

- R&D

Q & A

Q: where do we focus in ICT training for teachers? A: Probably most innovation comes from digital literacy, from the capability to analyse, criticise and assess, which somehow requires exploration.

Q: how do we teach how to innovate? A: a pedagogical shift is required prior to engage in innovation.

Q: where do we put the threshold in what is “sufficient” e-kills? A: it depends. This is why we have to draw standards depending of economic sectors, purposes, etc.

Ismael Peña-López: there’s evidence of ICTs being not a driver of inclusion, but a driver of exclusion: the question is not whether I’ll be more employable if I got specific e-skills, but whether I’ll remain employable at all if I do not have them. On the other hand, is not about e-skills, but e-competences. Skills might vary as technology does, but competences do not (e.g. a competence is going from A to B as fast as possible; skills, which change along time, would then be riding a horse, riding a bike or driving a car).

Q: if ICT in education is useless, because teachers are not prepared or committed, why don’t focus in informal learning? is it worth it? are policies correctly addressed?

Edgar Gómez: there’s a problem of fundamental skills like reading, talking and speaking, that undermine higher level skills.

Ismael Peña-López: why focus in informal learning? why not fix what’s broken (formal education) instead of fostering a patch (informal education)? (note: I’m actually for informal learning). A: Fixing formal learning is really costly — and not only economically — and its success, when there’s some, is long term. It might be cleverer to make technology pervasive and invisible in every day life, and make using it (and learning its use) more transparent and also pervasive. It’s not about teaching, but about embedding. It’s about making irrelevant the computer by using it very much.

More information

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 24 March 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Knowledge Management, Meetings, Online Volunteering, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

4 Comments »

Andalucía Compromiso Digital is a volunteering project to foster the use of Information and Communication technologies amongst the Andalusian citizenship, hence, an ICT volunteering project.

On March 27 to 29, 2009, the first Encuentro Andaluz de Voluntariado Digital (Andalusian Conference on ICT Volunteering) will take place in Jaén (Spain) to reflect about the past and draw applied strategies for the future.

I have been asked to make a speech about the impact of the Network Society in our daily lives, especially in everything related to access to knowledge and how this fact determines participation and engagement. I am to frame two following speeches by Juan Sebastián Fernández Prados on volunteering in the Network Society, and Pilar Jericó on personal skills for volunteers to network with people in risk of e-exclusion, thus why I’m standing on a quite theoretical level.

My speech has two main parts:

- A first part on development, network society and the different natures of the digital divide.

- And a second part on the role of knowledge and digital literacy in determining e-inclusion and, most important, social exclusion.

More information

Acknowledgements:

I want to thank Isabel Díaz for her kind invitation and Antonio “Nono” Pérez for just making it possible.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 11 March 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Education & e-Learning, ICT4D, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: idpac, UNDP

No Comments »

The Escuela Virtual para América Latina y el Caribe (Virtual school for Latin America and the Caribbean) is an organization (depending from the UNDP) whose mission is to build capacity and impart training in the fields that can promote social transformation, namely human development and democratic governance. As its name reads, it is a fully online school and uses ICTs as a means; but it is also worth noting that the Virtual School is in itself a showcase on how to apply ICTs in Development (ICT4D), specially in what we’d call e-Learning for development.

A successful project, it is now in its way to train other organizations not only in their missionary content, but also in the “how to” part of the story: how to build up a virtual school (for government, for empowerment) in Latin America. These days (10th to 12th March 2009) it’s taking place a training-consultancy for people at the Instituto Distrital de Participación y Acción Comunal de la Secretaría de Gobierno de la Alcaldía de Bogotá (IDPAC: Participation and Community Building Institute at Bogotá, Colombia), so that they can build their own Virtual School of Local Participation.

I have been invited to give a conference on e-Learning for Development, entitled La Brecha digital y el uso de las TIC para la Educación (The Digital Divide and ICTs for Education).

The presentation has four different parts:

- Slides 1-6: A brief introduction and some highlights about the crossroads between participation, governance, human rights and the changes that the Information Society is bringing in. The topic just frames my introductory presentation, and is later on developed in depth by professor Jaime Torres, Universidad de los Andes.

- Slides 7-12: Second part is a characterization of the Digital Divide. It actually is about the digital divides, which is absolutely my point: there are many of them, and most of them usually kept out of the spotlight.

- Slides 13-21: Third part is about networks. It is focused in development and development cooperation. There’ll be time to explore online volunteering, development 2.0, the gift economy, etc.

- Slides 22-31: A last part is about (how great it is) e-learning for development issues, from different points of view: efficacy, efficiency, suitability, convenience, etc.

Citation and downloads: La Brecha digital y el uso de las TIC para la Educación.

I want to thank Andoni Maldonado and Gemma Xarles for their kind invitation, and to Nicolás Padilla for assistance and patience.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 03 March 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, e-Readiness, ICT4D

Other tags: icd_development_index, idi, itu

2 Comments »

The International Telecommunication Union has published their new ICT Development Index, measuring 11 Information and Communication Technologies indicators for 154 countries, and calculating its value for 2002 and 2007, so that comparisons can be made available.

The ICT Development Index (IDI) is a merger of two previous indices: the Digital Opportunity Index and the ICT Opportunity Index. From the DOI it takes indicators related to households and broadband and the methodology and presentation, while from the ICT-OI it takes indicators related to skills, the normalization method and the digital divide analysis and methodology.

This merger responds to the proposal — and need — of the ITU and other international agencies to concentrate all efforts in just one multi-purpose measuring device, instead of having several complementing indices fostered by different organizations. So we should congratulate all agencies contributing to making this possible for that effort.

But. While some consensus has been reached, the cost of is that the new index has evolved towards a lowest common denominator. In our opinion, losing the information that affordability brought to i.e. the DAI is a loss of shades that were of most utility. This way, the new index is more polarized and is mainly intensive in infrastructures and just shyly on usage and skills, leaving a big void in all other aspects of digital life: the ICT sector, digital skills (the new index uses but proxies) or the legal framework.

On the other hand, the most interesting thing to highlight from this index is that, unlike most other indices, the coefficients of the weigths assigned to each indicator and subindex are calculated statistically, using principal components analysis. Undoubtedly, this provides much legitimacy to the final index values, at least at the formal level.

To clarify the evolution within the UN Sytem of how ICTs have been measured we have prepared the following scheme:

More brief information related to these indices can bee accessed in the following links:

More information

Note: I want to thank Ivan Vallejo from the ITU for his quick and effective answer to my requirement. ¡Gracias!

92.5 KB). The main statements of this section are as the following, which I’ll be commenting one by one.

92.5 KB). The main statements of this section are as the following, which I’ll be commenting one by one.