By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 17 September 2013

Main categories: Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: sandra_gonzalez-bailon

No Comments »

Sandra González-Bailón, Professor at the Annenberg School for Communication (University of Pennsylvania)

The self-organisation of political protest and communication networks.

Cyberactivism: there has been an obvious drastic reduction of costs of participation. May this be the reason more people are willing to engage in politics? Will these movements last in time? How do they work? How do they grow or are managed?

There also seems to be a certain degree of contagion of social movements: information flows through networks and enables new protests that replicate previous ones. Indeed, social networking sites help in putting in contact different and isolated communities, which also makes it easier for mobilizations to spread.

Network theory, network analysis and big data are being very handy tools for analysing what is happening in the field of social movements.

Threshold models

Watts, D.J. & Dodds, P.S. (2010). “Threshold Models of Social Influence”. In P. Bearman & P. Hedström (Eds.) Handbook of Analytical Sociology. OUP

Threshold models measure the likelihood that someone will do something above a certain threshold or number of people have already decided to do or have already done something. E.g. if your threshold of buying a new smartphone is 20%, you will decide to buy your new smartphone once 20% of your friends/network has already bought it.

- the shape of threshold distribution determines the global reach of

cascades;

- individual thresholds interact with the size of local networks;

- critical mass depends on activating large number of low threshold actors that are well connected in the overall structure;

- exposure to multiple sources can be more important than multiple exposures from the same source (complex contagion)

The Spanish indignados movement or 15M

The Spanish indignados movement is highly hierarchical (high average degree), as most of online networks are. And the people that are in the core of the network tend to interact with other nodes in the periphery of the network (very low level of assortativity).

Most of the users had medium threshold levels — neither pure leaders, nor pure followers. What can be seen is that, actually, users with lower threshold values used to tweet at the beginning of the demonstrations while users with higher thresholds used to tweet later in time (i.e. a demonstration of the threshold model). When analysing the information cascades, once again it can be evidenced that messages spread virally and very quickly.

Where are recruiters or influentials and spreaders? The k-shell decomposition helps us to tell the degree of centrality of certain individuals or Twitter users. What we see is that recruiters do not necessarily belong to the core of the network, but are randomly distributed along the networks. But when it comes to analysing the lenght of the cascades that they initiate, core users spark longer cascades. In other words, messages are not always initiated at the core, but longer chains of messages are.

Thus, the power of networks have a relative weight, but hierarchies still have much weight in the diffusion of messages.

González-Bailón, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J. & Moreno, Y. (2013). “Broadcasters and Hidden Influentials in Online Protest Diffusion. American Behavioral Scientist.

Four type of users according to centralily and comparing ratio of mentions received/sent and ratio of following/followers: influentials (high ratio of received/sent, low ratio of following/followers), broadcasters (low, high), hidden influentials (high, low), common users (low/, low). Influentials usually initiate longer cascades.

Related to the evolution of the movement, at least what data say is that the first anniversary in 2012 was less concurred in terms of people tweeting or participating through Twitter. On the other hand, centrality grew, which means that hierarchy grew too. Why? Maybe because the leaders were less able to mobilize other people, maybe because these leaders became stronger leaders along time. Again, cascades in 2012 grew less than in 2011, which means that the reach of the message was shorter. Thus, more hierarchy and less reach. This evidence goes against the motto of “horizontality” of network-based citizen movements. When hierarchies are measured with Gini-coefficients, it becomes obvious that unequal distribution grows in all categories (influentials, etc.).

One of the consequences of this evolutoin of the network is the cloaking of the network: influentials become less large and more central, and thus they centralize more the debate. And sooner or later the risk of not being able to manage such centrality in the path of communications end up in cloaking the network and making it much weaker.

Brokers are people that bridge separate networks. It can be seen that brokers have low levels of structural constraint and actually send tweets with aim at putting in contact these different networks (e.g. by means of sending tweets with hashtags that belong to the “vocabulary” of more than one network). They sent more messages, got more retweets (RT) and received more mentions.

The problem is that there are just few brokers, which, again, pose a problem of cloaking the communication between networks would they disappear.

Conclusions

- They are not horizontal structures.

- They are not stationary. They are dynamic and change in time.

- They are not robust and fluid: they have structural “holes” that difficult the processes of diffusion.

Discussion

Q: Is Twitter a social networking platform? And how does this affect the analysis? González-Bailón: it certainly is more than that, as it has a broadcasting component. And this sure affects the analysis as it fosters centrality and hierarchy more than other SNSs such as Facebook. On the other hand, some users are actually collective or institutional users, which also affects the rule of the game.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 25 August 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: e-democracy, social_movements

No Comments »

The following paragraphs do not intend to present an idea particularly new, although I think it is pertinent to say that they seek to revisit an old idea under a new context.

On the other hand, this is more an intellectual exercise — or even a speculation — rather than an academic proposition. However, it is fair to acknowledge that this exercise does not appear out of the blue. On the contrary, it is firmly based on two recently published works and the respective bibliographies that support them:

- Casual Politics: From slacktivism to emergent movements and pattern recognition (bibliography).

- Spanish Indignados and the evolution of 15M: towards networked para-institutions (bibliography).

Finally, although this discussion has been cooking in the oven for the last few months, I can not leave unsaid that Daniel Innerarity’s latest op-ed — ¿El final de los partidos? [The end of parties?] — has been the final trigger. The article — a highly recommended reading — goes on to state that although the world has changed, the institutions of democracy (governments, parliaments, political parties, unions, nonprofits, etc.) are still the best way we have to organize our lives in society. And that these institutions being reformed, but in essence those are the ones we have and the ones we should be keeping.

Institutions and democracy

Les us simplify as much as possible — with the consequent risk to fall into inaccuracies, generalizations and biases — what is a liberal democracy.

Since policy is no longer the management of the polis, citizenship has been alienated from the exercise of directly and personally ruling public affairs. This is no answer to no plan hatched in the dark to uptake power, but mainly responds to reasons of efficiency: the polis has become a county, a region, a state, a global world that requires full-time leaders, professionals that can manage the enormous complexity of politics and that, of course, serve all citizens and respond to them and their needs. No one can afford devoting themselves to managing public affairs and, at the same time, managing personal matters and earning their livelihoods. At least not without the slaves who had our Greek ancestors (some of our contemporary representatives actually have someone working for them, or just neglect public affairs, but this is another matter).

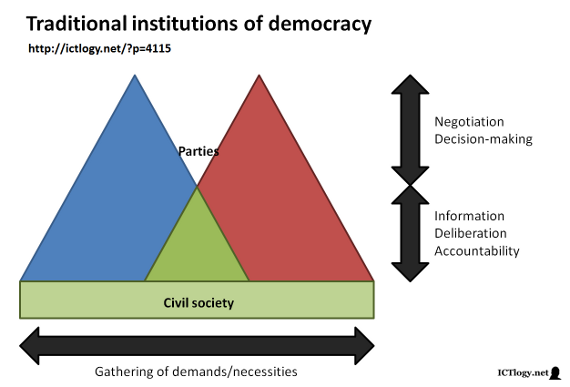

We have created, thus, institutions that represent us politically and work for everyone. At the lowest level of those institutions (e.g. political parties or labour unions) many citizens participate (joining, sympathizing, collaborating) to gather information on the needs and demands of their peer citizens, as well as deliberating on the various possible solutions.

At another level, a few representatives (governments, parliaments) are responsible for making decisions, after having negotiated the wills of the various groups represented. At the end of the cycle, this level ensures accountability of the decisions made before the lower level.

The general population, given the difficulty of being informed and engaged, remains outside the whole process and only follows it remotely through the press, political propaganda and punctual moments of participation through the ballot box.

Crisis of institutions

There are at least four reasons why current political institutions have seen their legitimacy diminishing in the process of representative (or institutional) democracy:

- Because the professionalization of their boards has become not a means but an end in itself. Staying on the job happens to be the goal of many in office, getting out of line of what should be their genuine purpose: to serve the citizens they represent. This deviation or sheer abandonment of the original mission of the institutions, of course, has happened at the expense of the legitimacy and the gradual withdrawal of citizenship.

- This professionalization has crowded out from the foundations of the institutions those citizens who saw participation as a vocation of service and not as a professional vocation. This expulsion may have been active or reactive, but the results have been clear: thinning of the bases and withdrawal (again) of the bulk of the citizenry.

- The increasing complexity of politics, together with the professionalization and the brain drain of the institutions has resulted in the worst of situations: trivialization and playing down of the complex, simplifying the political message and its consequent radicalization of ideas. The political debate becomes meager, addressed to media, puerile, rather than strengthening deliberation and seeking learning in the democratic process. In the absence of political pedagogy, behold disaffection.

- Last but not least, many of the previously mentioned issues may not have a solution, but they could in deed have a strong contribution thanks to the new Information and Communication Technologies (information and communication: how often we forget the meaning of the acronym ICT). There are many things that ICT could help on: encourage participation and engagement of talent, transparency and accountability, dialogue and debate. If they are not a magic solution, their negation itself is a clear statement of principles: although the use of ICTs may have great potential in all areas of politics, we have no intention of putting them into practice and realize this potential. More disaffection, especially from the ones who could and would participate.

Consequences?

On the one hand, the thinning of the bases of the institutions, especially those closest to the citizenry (parties, unions). On the other hand, the shift of information and accountability “upwards”: the same ones that negotiate and make decisions are the same ones that are informed about what is “necessary” or “convenient” being done, and are also the same ones that are accountable amongst themselves.

The result is a growing disconnect with the society due to the shrinking of the social bases and the lack of in-depth, “vertical”, technical and political paths of the implemented policies. Deliberation is not only absent but even avoided. Without information, citizens can not deliberate. Indeed, without being “professionalized”, the citizenry becomes a hindrance to decision making. Everything for the people.

Social movements

Kicked out by institutions, empowered by digital technologies and spurred by the crises (increasingly less cyclical and increasingly more structural, given the speed of change in the new Information Society) citizens organize themselves. Oblivious to the institutions. Even despite institutions.

They organize, and it is worth emphasizing it, the do it in a horizontal way, away from the verticalities of the party hierarchies. And they do it horizontally for two main reasons:

- Because this is the architecture that the new technology — the great enabler of new organizations — promotes above all. One person, one node. While there actually are leaders, they are leaders to the extent that they contribute to the cause, not to the extent of them thriving within and up the organization. And they are leaders while they are facilitators, not fosterers: facilitating the work of the entire network, not just staging their own personal and individual projects.

- Because the new binders are the projects, not big enterprises. While it is true that, by aggregation, projects can generate programs and programs can generate these strategies, in the new movements what is important is trees, not the forest, fishes, not the bank. The initial goal is to save my home, not to change the housing law, while larger institutions begin to change the law and, if given the circumstances, save a handful of homes. And that’s what it means “bottom-up”: not only where the action starts, but the fact that the overall process is reversed.

The problem, as can well be seen in the example above, is that the translation from horizontal to vertical is very complicated. And the shift from project to strategy, from local to global, from what is personal to what is public does require a certain verticality.

It is at this point where I personally agree with those defending tooth and nail the existence of institutions. And it is certainly a crucial point that separates me/us from those who opt for the elimination of the institutions or their reduction to a minimum — and this includes assembly-based movements and anarchists, but also, and it should not be forgotten, extreme liberalism (extremes always meet).

But that we need institutions does not mean that (a) they necessarily have to be the ones we already have, or that (b) even if we keep the ones we have, their design should be the same one they now have. Or, put another way, there is much room for debate between maintaining the status quo — the democratic institutions should be the same ones we already have — and demolishing any semblance of institutionality — direct and/or assembly-based democracy.

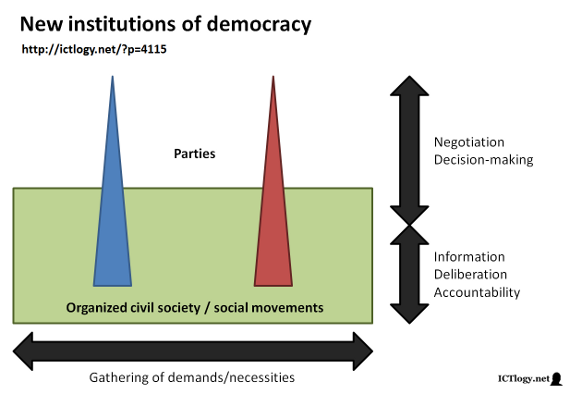

In a world of shadows of grey, away from black or white, there surely is room for a possible hybridization of organized citizens and traditional institutions. This reflection began by saying that the idea was not new, but the context was. It is possible that the great institutions of the past must now split into different institutions, some older ones (parties, unions) who will come to live with some newer ones (or not so new, but refurbished in their inner organization: platforms, movements). I believe that many of the functions taking place inside the classical institutions may end up taking place outside of them and within new institutions. Efficiently and effectively conveyed by technology, without barriers of time and space, it seems possible and even desirable to me to return the information back to the base, to the new institutions of the civil society that will extend the length and breadth of the citizenry and citizenship. Moreover, if there is a place where deliberation — an informed deliberation — can happen, where better than out under the daylight, among peers, with total openness and transparency. Ditto for accountability.

For the rest, to link the global with the local, the collective and the personal, to “verticalize” the demands into decision-making, traditional institutions surely will continue to have an important role… although with severe transformations: like learning how to listen, how to network. They will arguably be much more flexible, probably smaller; relegating power, shifting representation and many other tasks towards the new social movements and civil society organizations. They will have to work together and, therefore, establish ways to collaborate, to mutually enrich themselves, to share the work.

In short, the grassroots levels of the parties should probably be “outsourced” and keep parties not as think tanks or policy-making industries (which largely have by now ceased to be) but facilitators and implementers of proposals. About leadership, the civil society will sooner or later take over.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: david_fernandez, higinia_roig, postdem, ricard_vilaregut

3 Comments »

David Fernàndez. Parliaments. The CUP: one foot on the street, one foot in the Parliament.

We are living the complete exhaustion of the current regime, including a deep defeat of the ideologies of the left.

One of the main factors of this exhaustion and defeat is the privatization of politics: the statement that politics have nothing to do with the citizenry. This paved the path of the total privatization not only of politics but of everything that was the common interest, ending up in the privatization of the welfare state.

Should we recover the institutions as we knew them? Should social movements enter these institutions?

Indeed, there already are many institutions working within the system but with different mindsets such as Coop57, SomEnergia. Xarxa d’Economia Solidària or La Directa.

The CUP benefits from all the social movements that are initiated just after the death of the Dictator Franco and the recovery of the Democracy in Spain. Of course, all the anti-globalization movements of the late XXth century and beginnings of the XXIst century. Deeply rooted in municipalism, the CUP begins to create local assemblies to concur to the municipal elections all over Catalonia, being part of the Parliament out of the question.

But the changes in the way of doing politics and the change in the sensibility of Catalonia regarding nationalism and independentism, the CUP decide to concur to the national elections and win three seats in the Parliament.

The three main courses of action are popular activation, civil disobedience and building of alternatives.

It is a crucial strategy to recover the commons and the common good for the citizenry. In material or infrastructural terms — recovering the assets and the strategic resources of a territory/community — but also in terms of superstructure — recovering the governance of the several institutions that have exert power over the citizenry or can influence public decision-making.

Power is not a space, but a relationship. Thus, if one aims at changing power, one has to change a relationship of power, a relationship usually between two parts: a third party and oneself. Changing relationships of power, thus, begins with changing one’s own practices.

Ways the whole thing can change: feudalist capitalism , democratic fascism or any other form of subtle authoritarianisms, or an egalitarian solution.

Discussion

Arnau Monterde: how is made compatible being in the Parliament and being an assembly-based party on the outside? David Fernàndez: “It’s complicated”. The way it is done is creating 15 work groups within the organization which translate their diagnosis and decisions to the MPs so that they can use the information and decisions in the Parliament. There are also geographic groupings that help to vertebrate the territory.

Ismael Peña-López: technically speaking, the commons is a privatization of the public goods. Is privatization the way to (re)build the common sphere? David Fernàndez: we should separate the goals from the ownership of the commons. If the commons are headed towards providing a public good, this is what is most important, more important than technical ownership. There is no much difference between common and public. In this scenario, private/common ownership is only a second best when one cannot dispute the design of the State and how power is distributed.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: ada_colau, pah, postdem

3 Comments »

Ada Colau. Citizenry. The PAH: from the ILP to the ‘escraches’

We are living the end of a regime, kidnapped by corrupt political en economic leaders. And the regime needs a renovation. How?

How do we rethink social organizations? There is no regeneration of democracy without a strong and well organized civil society. The solution, if any, is not expected from the institutions that corrupted democracy from within. Only a watching and alert civil society will enforce the correct government, as power naturally tends towards corruption.

This social organization, besides its role to watch the power, needs also new forms. Because most organizations nowadays have not aged very well. This includes political parties but also labour unions and NGOs: organizations that were very useful when they were created but that have become useless to provide answers for today’s problems.

The problem is that we [Spaniards] have not been educated into Democracy. We have always been told not to participate in politics. We need to be critical against corrupt institutions, but also self-critical with ourselves and our not-being involved with politics.

And empowerment is the word, the way to do politics (again), to win back for the citizenry the agoras, the squares, the collective discourse, etc.

Back in 2008, before the government and the population in general realized the problem of the housing speculation in Spain, the Plataforma d’Afectats de la Hipoteca (PAH, Platform for people affected by their mortgage) was created to weave a network of people with a common interest. The worst error then was staying in “maximalism”: remaning on the theoretical approach, on the macro approach, on raising awareness on the issue of evictions and personal debt… but not going into action, addressing specific issues, very concrete problems.

The new initiatives of the PAH then attacked several issues in the short, medium and long run, with plural strategies that would address both the macro and the micro levels, the economic crisis and the individual drama of a given citizen, etc.

The Platform succeeded in mobilizing people that had no experience in being mobilized and that did not even had the will to do it: instead of angry people aiming to fight for their rights, the Platform found devastated people being stigmatized by the society. The Platform provided a new mindset, a new context, and a new strategy to overcome the problem: instead of lamenting oneself, fighting for one’s legitimate rights.

Another success was empowering people: it is you that will solve your problems, not anyone else, not the Platform. But the PAH will empower you so that you are able to solve your own problems: no one will defend your case better than yourself. But by oneself does not mean alone, but, on the contrary, collectively and, above all, in a shared way.

All this activity has been done with almost no resources. The person that becomes empowered is reborn and helps others to go through the same process. High level politics can be done with almost no money

.

A last resource for activism is civil disobedience. If a law is unjust, it is not only fair but a duty to fight the law back by disobeying it.

Besides civil disobedience, and in parallel, the mainstream way was also taken, by means of a popular legislative initiative. Of course no practical success came out of it, but two major successes came out of it: raising huge awareness on the topic and de-legitimizing the ones in the Parliament that were proven to be useless to citizen problems even if those were channelled within the system itself.

The main challenge is how to substitute the old mechanisms and institutions with new ones. There is a need for some form of organization: participative, non-hierarchical, democratic… but a form of organization in any case.

Discussion

Q: changes, but towards which way? what scenario can be envisioned? Ada Colau: the horizon is not clear and, above all, we should not rush it. What is clear is that we have to open processes of debate and processes to design this new scenarios. And do not delegate these processes but, instead, be ourselves the main actors. Some urgent initiatives or issues to be addressed is fighting corruption, sanitizing institutions by changing their design (by changing the regulatory framework that shape them), etc.

Q: how do we design the communication strategy? what kind? Ada Colau: this is very difficult because mainstream media react depending on many factors. On the other hand, media tend to identify the movement with one spokesman or visible head. Thus, even if the movement plans a decentralized strategy based on a collective message, while the identification with a specific spokesman works for the movement, ok with it.

Arnau Monterde: how does the movement replicate? Ada Colau: empowerment is without any doubt the most important part of it. Notwithstanding, replication has been an issue from the very beginning: the movement should be able to be replicated, de-localized, decentralized, so that it became sustainable and could grow. Information, procedures, etc. have always been shared and socialized. The movement has taught not only the end users or the members, but also the professionals have been retaught in new ways of sharing their expertise and provide advice openly.

Ismael Peña-López: what is the legitimacy of a Platform such as the PAH to speak with other institutions? Ada Colau: first of all, elections have been proved not to legitimate parties, especially when they do not carry out their own political programmes. On the other hand, anyone can represent the defence of human rights: what the PAH does is to remember that human rights cannot be violated, and asking for respect for the human rights is a duty for everyone.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: postdem, ricard_espelt, roger_pala

4 Comments »

Roger Palà. Media. Mediacat and the Yearbook of the media silences.

Media are suffering a crisis of legitimacy as important as parties’. Indeed, media are reproducing all the bad practices that other powers are. How can we re-legitimze media? How can we return media to their role as watchdogs and not as part of the power? This crisis of legitimacy has been running for at least 15 years. If they have emerged now is due to two main reasons: (1) the financial and economic crisis that have deepened the crisis of journalism, as they lack more now resources and (2) the emergence of social networking sites.

There has been an important devaluation of contents due to lack of resources but also due to accommodation of the professional. This has ended up with bad practices like do not checking the sources, lack of self-criticism, etc. But changing the system from within (i.e. Association of Journalists) is very difficult, so the Grup Barnils opted for initiating some activities “in the margins”. With Media.cat a project was created to point at bad practices in journalism, creating reports on the state of the question of media, etc. The flagship project is the Yearbook of the media silences.

But the point (of the yearbook and in general) is not a general criticism against media, but raising awareness on the crisis of the sector, the reasons for the crisis and the ways to try to fix it. The approach, in fact, is rather constructive and awards the good practitioners more than condemning the bad practitioners.

The Yearbook has had increasing success and one of the reasons is twofold. On the one hand, because it has raised a lot of awareness on the issue and, on the other hand, because it has relied on the citizens to back the project, through crowdfunding initiatives but not only, as citizens have spread the word about the whole process and not only about the final outcome.

The con side of the initiative is that it is a one-time-a-year thing, not very fairly paid and with difficulties of sustainability.

The good thing is that despite being a very small collective, an impact has been made, especially in the field of media.

Discussion

Q: is it true that social networking sites make it more difficult to hide things? Roger Palà: absolutely. A good thing of social networking sites is that they break the monopoly of the agenda-setting.

Arnau Monterde: what is the future of media? is it possible a network-based model? will we see for long the traditional model of mass-media? linking the economic crisis with the crisis of media, is it legitimate? Roger Palà: it is absolutely true that money enables professionalism and professionalism usually enables quality content. This does not mean that media have to be big: we are witnessing the emergence of small initiatives that, despite being small, they are 100% professional and are looking for new niches and new ways of working. We will surely see a new cosmos of few big media and a constellation of small media living together.

Q: isn’t there room for citizen journalism? Roger Palà: yes, sure, but the problem is sustainability in the long run. Is it possible to sustain quality and engagement and professionalism without a comfortable economic position? Maybe, but stability helps a lot in sustainability.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: loudes_muñoz_santamaria, postdem, psc, xavier_peytibi

3 Comments »

Lourdes Muñoz Santamaría. Parties. PSC BCN: network party, open party

Political parties do have to change, but they have to keep their ideology and the focus on the common interest.

But it is true that we are in a change of paradigm and a change of era. And thus institutions have to change, especially to be able to understand the needs of people and provide valid answers. To do so, politics have to be much more participated. And social-democracy is speciallly fit to lead this transformation, as they believe in serving people from the power of institutions.

There is a problem when people, as individuals, have taken up web 2.0 and social networking sites as multi-purpose tools, but institutions have not. Partly because the paradigm of sharing is not in the ADN of most institutions.

Indeed, sharing relies heavily on access to information and access to knowledge.

The idea behind the open party is to apply to a party the concept of open governance that applies to governments. That is, openness in decision-making, access to information, participation, engagement, etc.

The main reasons to carry on this project is, above all, conviction. The necessary reformation of the PSC-Barcelona was not only about content, but also about forms.

And this change is especially about changing all the processes. Smoothly, so that no-one is left behind, and everyone can have a chance to learn the new ways.

One of the debates just before the project was whether the party needed a “cyberpartisan” or a “web 2.0” initiative. But the party decided that people were not “normal” vs. “digital”, but a single one: so, the idea of the open party is that it will cut across all sections and initiatives.

Principles of the network and open party:

- Transparency: all decisions, all debates are open. All the information required for participation is openly available.

- Virtual participation is an effective right. Deliberative democracy, e-voting. There is too much distance between “liking” a status in the party’s Facebook page and participating in a local meeting of the party. These two worlds have to be bridged.

- Project-based work, instead of department-based work. This enables people to participate in whatever their interests are, without having to participate on a binary basis: all or nothing.

Goals:

- Adequate the party to the society.

- The conviction that the public space has changed, and thus have changed the roles of political intermediaries, media, the way the public opinion is made up and shaped.

- Increase the possibilities to commit with a party, with a specific initiative.

- Combine openness in deliberation with spaces of privacy that enable consensus and negotiation, without entering into opacity.

- Build a deliberative democracy.

- Stablish more ways of direct relationship with the elected representatives.

Discussion

Roger Vilalta: are big traditional parties still on time to retune with the citizenry? Or is everything already lost? Lourdes Muñoz: this is certainly the question. What is clear is that things will never be the same. An obligation for the party is to do this reform well and quick. And just hope that the new procedure will attract if not new people, at least the ones that left.

Marta Berenguer: does openness represent a chance to break the discipline of the party? Lourdes Muñoz: a debate has to be as open as possible, but the final position has to be unique. Thus, party discipline is good not to mislead the voter and to have a higher negotiating power [note the Spanish context to frame this answer]. What fails, thus, is not party discipline, but the internal dialogue and debate.

Joan Carles Torres: is it to believe initiatives as such, or is it just make up and marketing? The problem is that transparency has become a cool trend that everyone seems to be embracing. So, can politics be transformed with initiatives like this? Lourdes Muñoz: it is true, it is difficult. But we have to begin somewhere and this is one way to do it. Let us just hope that it works, that it can spark a change from within.

Q: what can guarantee that transparency and participation will actually be enabled? Lourdes Muñoz: there are no guarantees. This is just a beginning, a new way to try to transform how the party works on its inside (especially) and towards the outside (in more general terms). There are three problems to be addressed: learn how to facilitate; how to identify the relevant stakeholders; how to put the decisions made into practice.

More information

Post democràcia, partit obert, by Lourdes Muñoz Santamaría.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)