By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 25 October 2009

Main categories: Connectivity, Digital Divide, ICT4D

Other tags: cybercafe, e-centre, telecentre

2 Comments »

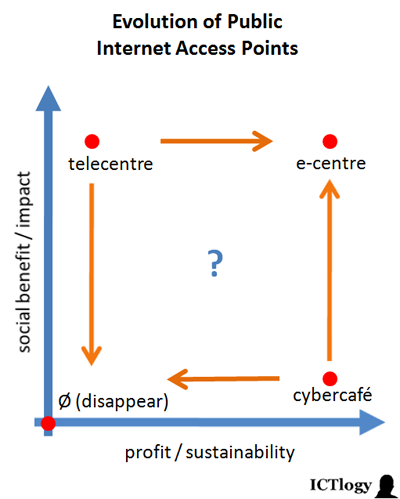

Let’s imagine there are only two kinds of Public Internet Access Points, that is, a place, different to your house or your work where you can connect to the Internet:

- A library, a civic centre, or an ad hoc place equipped with computers and connection to the Internet; access and usage is free because its supported by public funding or private not-for-profit funding. Its goal is philanthropic and aimed towards making an impact on people’s livelihoods: empower them to fully achieve their citizen rights, help them to climb up the welfare ladder, etc. Let’s call them telecentre.

- The other kind is similar to the previous one but it is not free. And it is not because its aim is to return the investment the owner made — an entrepreneur — in the form of revenues that will hopefully become profits, that is, costs will be lower than revenues. Let’s call them cybercafé.

Things are quite more complex and reality constantly shows that there are not pure models. But let’s keep things simple, very simple, for the sake of the explanation.

If things were that binary, telecentres would be having an impact on people’s lives while cybercafés wouldn’t; on the other hand, cybercafés would be economically sustainable (self-sustainable) while telecentres would not.

Internet penetration: a double edged sword

Internet penetration is growing everyday, for several reasons: willingness to adopt because of increasingly perceived utility, lower costs, public policies to foster Internet access at home and work, etc. This increased penetration can have two direct consequences:

- As more people are connected, the remaining unconnected people will either be too poor/difficult to connect (on a cost/benefit basis) or just absolutely refusing to connect due to personal believes (refuseniks). Thus, it is likely that both governments and nonprofits will shift away from e-inclusion projects to other areas of development that have ranked higher in priority.

- On the other hand, less people will go to cybercafes, as the demand will necessarily be lower. Indeed, the more infrastructure focused are public policies to foster the Information Society (e.g. putting laptops on kids’ hands) the stronger will be this moving away from cybercafes.

So, what will the future of telecentres and cybercafés be like? More than answers, questions is what really arise:

- Will telecentres fade away and end up disappearing? If they were economically not sustainable (in the sense that they depended on third parties’ funding), will they shift towards cybercafes-like models? Or will some of them just remain to try and cover the needs of the ones left behind? How is it that some voices foresee the end of telecentres while bookshops and cheap softcover pocket editions did not succeed in getting rid of costly public libraries?

- Will cybercafes shift to more telecentre impact-like focus and less access-based business plans? Will they compensate their shrinking access market by expanding towards a capacitation-based market? Will they be providing more content and, especially, services? Will they create communities of people around cybercafes as it is already happening in cybercafes whose customers are e.g. mainly immigrants and gather together around the cybercafe?

- Will both telecentres and cybercafes evolve into enhanced centres (e-centres), where communities will gather and benefit from several community resources, computers and Internet access among others? Or will they just disappear?

Fortunately or unfortunately, things are neither that simple nor static and are way more complex and dynamic in reality. But these are, nevertheless, questions that both decision-takers and tax-payers should be taking into account so to be prepared for what is going to be next.

As libraries have provided more than books, but a place where to learn to read and find kindred souls, it is my guess that public Internet access points will disappear as such, and will either be embedded within existing structures (libraries themselves, or civic centres, to name a few) or the existing telecentres and cybercafes will evolve into a next stage where the learning and community factors will be much more relevant. We are indeed seeing plenty of examples of this, and it is a matter of time that priorities or the focus turns upside down: instead of going to access the Internet and finding people, one will go and find people and use the Internet as an enhanced way to socialize. At its turn, this should be accompanied by the end of this false dichotomy on whether you’re a citizen or a netizen, as if the Internet had a life and a citizenry on its own. But time will tell.

NOTE: I owe some of this reflections from conversations with people I met at IDRC on my visit at their headquarters in Ottawa: Florencio Ceballos, Frank Tulus, Tricia Wind, Meddie Mayanja, Silvia Caicedo and Simon Batchelor (the latter from Gamos).

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 10 July 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: idpac, UNDP

No Comments »

For the next month (July 13th to August 7th, 2009) I am teaching — actually guiding — a course on the Digital Divide and e-Participation at UNDP‘s Escuela Virtual para América Latina y el Caribe [Virtual School for Latin America and the Caribbean].

This is part of a project run by the UNDP and the Instituto Distrital de Participación y Acción Comunal de la Secretaría de Gobierno de la Alcaldía de Bogotá (IDPAC: Participation and Community Building Institute at Bogotá, Colombia) whose main outcome will be the creation of the Escuela Virtual de participación y gestión social del IDPAC [IDPAC’s Virtual School of Local Participation] — see also Digital Divide, Government and ICTs for Education.

The course is framed in one of the last stages before the actual creation of the Virtual School and it mainly deals with the definition of the overall strategy, identifying the context and the characteristics of the environment and see how the network of telecenters the school will heavily rely on have to be adapted to provide the expected output: digital competences and a much higher degree of e-Participation amongst the population.

The (my) course has four parts, two of which are related to knowing the grounds and concepts of the Digital Divide and e-Participation, and the remaining two deal with writing an Action Plan and reviewing the Strategic Plan in the framework of the Colombian Plan for the Information Society.

I here share the bibliography for the first two, would it be of any help to anyone: Brecha Digital y e-Participación ciudadana

Basic concepts: Analysis of the Digital Divide

Ministerio de Comunicaciones (2009).

Plan TIC Colombia. En Línea con el Futuro. Presentation by María del Rosario Guerra, Ministra de Comunicaciones, Bogotá D.C., mayo 28 de 2009. Bogotá: Ministerio de Comunicaciones de la República de Colombia.

e-Participation: Use of telecentres to foster participation

Peña-López, I. & Guillén Solà, M. (2008).

Telecentro 2.0 y Dinamización Comunitaria. Conference imparted in El Prat de Llobregat, November 5th, 2008 at the V Encuentro de e-Inclusión, Fundación Esplai. El Prat de Llobregat: ICTlogy.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 09 June 2009

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, e-Readiness, Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: i2tic, jordi_graells, marta_continente, sessions_web

10 Comments »

On Wednesday 10th June 2009, I’m giving a conference at the Centre d’Estudis Jurídics i Formació Especialitzada, Justice Department of the Government of Catalonia (Spain). It is framed in the Web Sessions series to debate about the changes and impacts of the Information Society. My conference is called Darwin a la societat de la informació: adaptació (i beneficis) o extinció (Darwin at the Information Society: adaptation (and benefits) or extinction).

As the presentation shows, the speech is made up of four parts or general ideas:

- The industrial era — or the industrial economy — is based (among many other things) on two main issues: scarcity and transaction costs. These two limitations have shaped the world as we know it, especially institutions: schools, parties and governments, firms, civic associations… When shifting towards a knowledge based economy, both issues of scarcity and transaction costs fall down into pieces. Will institutions, and intermediation in general, follow?

- Second part is an overview on some of these institutions, and how their models and, sometimes, their sheer survival is threatened by these radical changes on costs and scarcity. Some will violently disappear, some will just fade, some will suffer adaptations along the following years. All in all, it’s about the risk of exclusion from society — not digital exclusion —, the risk of becoming worthless.

- Thus, there might be a need for new (digital) competences to face the present and the nearest future. These competences (to be acquired both by individuals and institutions) will be necessary to interact with each other and rebuild how we learn, work, or engage in politics or everyday life.

- To foster the acquisition of these competences some policies to foster the Information Society will have to be put to work, and the role of the government seems to be a crucial one

I will conclude that it all is a matter of bringing on changes while making sense of them.

More information

I want to heartily thank Jordi Graells for giving me the excuse — actually, to push me — to sit down and put together some ideas that had been rambling on my mind for some time. The title is his and it was great inspiration that helped me in weaving those ideas together. Not surprisingly, his work with the Catalan e-Justice Community (Compartim) is a most inspiring one too.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 20 May 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, e-Readiness, Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

6 Comments »

Some conversations with Ricard Faura — head of the Knowledge Society Service at the Catalan Government — about my recent research have triggered some questions that need being clarified.

The following lines are a very simplified approach on what I think should be the design of public policies to foster ICT usage in a place like Catalonia or Spain, though it is my guess that it can be extrapolated to most developed countries facing similar problems like Spain’s.

Barriers for adoption

In general — and again, being really simplistic with the analysis — there are three main issues identified as a barrier for ICT adoption in Spain and a third issue that, unlike developing countries, it is identified as not being a barrier:

- Age (and some would add gender) is a barrier: younger generations are way more online than older ones, being dramatic in elder people

- Skills present a barrier too, as people do not feel confident, or even threatened, by Information and Telecommunication Technologies

- Indeed, most people not using ICTs also state that they find them useless. Thus, utility and attitude are also a dire barrier and the one with a strongest trend.

- Last, and in general terms, infrastructures and affordability are not a barrier or, at least, they are not stated as being as important as other reasons for lack of usage.

Critique

I believe that the previous barriers can be summed up in just one single barrier: lack of utility of ICTs, with a stress on lack of utility on being online.

This lack of utility can be explained in two ways:

- A real lack of utility, mainly due to lack of digital content and services that fits one’s purposes, be them personal or professional: for leisure, for activism, for work, for training en education, for health, etc.

- A perceived lack of utility, mainly due to lack of e-awareness and not knowing the benefits (or a real measure of the costs) that ICTs can bring to one’s life. This lack of e-awareness, of course, can be accompanied by the lack of several digital skills, which create a vicious circle: less digital skills, less e-awareness; and so.

What about age? I believe that youngsters — besides the fact that they find ICTs not technologies but something that was always there since they were born — have already found ICTs useful: they absolutely fit their needs in matters of education (the Internet is full of stuff) and in matters of socialization (the “communication” part of ICTs), which are the two main “occupations” of people under 16.

Policies

So. We’ve got digitally illiterate people and people that cannot find in the Internet anything worth being connected. What to do from the government?

Concerning utility, my own research shows that pull strategies are the ones that work. It’s absolutely coherent, on the other hand, with trying the Internet to make sense for unconnected people. More hardware or software or broadband will just put stress on the citizen to use something for “nothing at all”. In my opinion, policies should be threefold:

- A high commitment to put public services and the dialogue government-citizenry online, by means of e-Administration and e-Government

- Help the private sector not to have an online presence, but to go beyond and use the Internet for their transactions, with the government (G2B, a part also of the e-Administration strategy) and with their customers (B2B and B2C)

- Last, but not least, empower the citizenry to bring relevant content and debate online. Citizen organizations (political parties, NGOs, neighbourhood associations, patient associations, foundations, clubs, etc.) would be my pick as huge impact collectives which to begin with, as they’ll have manifest multiplier effects by pulling other citizens towards the use of ICTs.

Concerning skills, there three groups of evidences that are worth being remembered:

- People with digital skills are more likely to be more productive and, hence, to earn higher wages. On the other hand, lack of digital skills is likely to reduce employability.

- People with digital skills go more online and happen to meet more people, which improves both their social engagement (and self-esteem and so) and their professional opportunities.

- Digital skills are, by far, acquired on an autodidact basis or, in the best cases, on a P2P basis (family, friends, colleagues). Formal training in digital skills is only partially present in schools and is rare past school age.

That said, and again in my opinion, policies should be threefold:

- Urgently mainstream ICTs — in a very broad and intensive sense — in curricula and syllabuses. This mainstreaming should be based in two approaches: (1) training for trainers and (2) embedding ICT practices in the overall learning process (i.e. not just bound to the computing subject or classroom — though I’m neither saying students should forget about pencil and paper)

- A proactive public strategy aimed to people out of the educational system to catch up with these skills, by means of telecenters and libraries (and other points of access), subsidised courses in computing academies, etc.

- A joint strategy with the private sector to do alike in their in-company training programmes. The public sector could provide training for decision-takers to raise their e-awareness and even help with funding in-company digital skills programmes. But, the private sector should be committed enough, as the benefits are evident and would sooner or later positively impact the firm with higher productivity rates.

Summing up

I honestly think that pull policies to trigger demand (trigger, not contribute to the aggregate demand with direct expenditure) would, sooner or later, trigger to a demand for training in digital skills, which implicitly states in which order I’d be setting these policies.

These what-to-do-policies also, by construction, set aside the what-not-to-do-policies. If we keep in mind we’re talking about (digitally) developed countries and their characteristics, policies not to foster are mainly those aimed at subsidising hardware or connectivity in any way, or fostering the creation and expansion of infrastructures and carriers without anything to be carried on. Static and eminently informational public or corporate websites fully fit in this category; and also fits in this category the creation of content with no further purpose or strategy of usage behind.

Some bibliography

Ficapal, P. & Torrent i Sellens, J. (2008). “

Los Recursos Humanos en la Empresa Red”. In Torrent i Sellens, J. et al.

La Empresa Red. Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación, Productividad y Competitividad, Capítulo 6, 287-350. Barcelona: Ariel.

Fundació Observatori per a la Societat de la Informació de Catalunya (2007).

Pla de Màrqueting de la Societat de la Informació. Barcelona: FOBSIC. Retrieved May 20, 2009 from http://www.fobsic.net/opencms/export/sites/fobsic_site/ca/Documentos/Escletxa_Digital/Pla_de_Mxrqueting_-_versix_per_a_difusix.pdf

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 May 2009

Main categories: Digital Divide, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, e-Readiness, Information Society, Meetings, Writings

Other tags: i2tic, phd

2 Comments »

Last May 14th 2009 I imparted a seminar entitled Measuring digital development for policy-making: Models, stages, characteristics and causes. The role of the government in the framework of the Internet, Law and Political science research seminar series that take place at the School of Law and Political Science, Open University of Catalonia (Barcelona, Spain)

Though I had previously presented part of my phd research in public, this is officially the first time that I present final results.

The presentation only shows a brief introduction to Part II (quantitative analysis) and partial highlights from Part III (quantitative/statistical analysis), which makes most slides quite cryptic without a speaker (more cryptic, I mean).

Put short — very short —, after defining a conceptual framework (the 360º digital framework) the research draws 4 stages of digital development (after cluster analysis), the three of which are but different levels of a similar digital development path, and the fourth of them a completely different digital development model: leapfroggers.

These stages of digital development are characterized (a profile for each of them is described), and some determinants (causes) for this digital development (or underdevelopment) are calculated by means of logistic regressions.

Main ideas/findings

The research shows the huge importance of governments in framing and fostering digital development, which is more important and should be more direct the less digitally developed is a specific economy.

It is important to note that government action should be, firstly, focused in framing and give incentives to the real economy, entrepreneurship and innovation; and secondly, to foster the digital economy by means of providing it with an appropriate policy and regulatory framework but also by means of “pull” strategies.

Thus said, the findings show that digital development is compatible with both liberal and Keynesian policies, and that supply-side policies and direct intervention are only worth applying below a minimum threshold of infrastructures. After some infrastructure is installed, policies should especially focus to trigger demand (not to increase the aggregate demand, which is a completely different thing).

This goes against the belief that the government should subsidise computers or content; but it also goes against the belief that the government should just care for the regulatory framework: public policies are a determinant of digital development.

What policies then? Fostering digital services, both private supplied as public e-services, as these services will pull de demand more effectively than other kind of policies.

Two caveats:

- Basic development (income, health, education, equality) accompanies any other kind of digital development, which means that it has to be addressed first hand and, indeed, be the target itself where to apply the benefits of digital development.

- Leapfroggers show that another model from the previous one is possible. It is my concern, nevertheless, how a model based in a powerful ICT Sector aimed towards international trade will impact the domestic economy beyond an eminently direct level. In other words, policies fostering a domestic digital development will have both direct and indirect multiplier effects, the latter being the most powerful ones and, maybe, absent in a leapfrogger model.

Citation and downloads

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 12 May 2009

Main categories: Development, Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Meetings

Other tags: apc, chat_garcia_ramilo, gem, gender, gender_evaluation_methodology

1 Comment »

Live notes at the research seminar Gender Evaluation for Social Change by Chat Garcia Ramilo, Coordinator of the Association for Progressive Communications Women’s Networking Support Programme, Manila (Philippines). Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Castelldefels (Barcelona), Spain, May 12th, 2009.

Gender Evaluation for Social Change

Chat Garcia Ramilo

Why gender evaluation? Evidence showed that ICT4D did not integrate gender considerations, though evidence also shows that effectiveness and impact of development projects increases if gender is integrated in design, planning and evaluation.

Based on participatory action research.

- Testing and development of a gender evaluation tool for ICT4D projects: teleworking, ICT training projects, telecenters, etc.

- Capacity building in gender evaluation: telecenters, rural ICT projects, ICT policy processes and localization (of content)

Findings and challenges

- a gap in capacity for analysis and evaluation of gender-based inequalities

- weak focus on gender in project design, implementatoin and policy formulation

- how to develop evaluative thinking about gender and ICT4D, and use it to shape new gender practices within the ICT4D sector? how to make it in a participatory action research framework?

How gender makes a difference in ICT4D and access to the Information Society:

- Comparative access to infrastructures by women and men are determined by income levels

- Capacity affected by literacy and education levels

- Services affected by relevance of service, mobility, safety issues

- Governance affected by opportunities for participation in policy processes

These aspects have to be taken into consideration if one is to design an ICT4D project in a specific place. The design of this project will sensibly be different depending on how gender is affecting the former issues.

But gender is not only about “women issues”, but also about social and cultural variables, how do the interplay of these variables impact on women and men.

The Pallitathya model

The Pallitathya help line Blangladesh center is a help desk service which consists in five basic components:

- local content

- multiple channels of information and knowledge sharing

- intermediation or infomediation, human interface between information and knowledge-base

- ownership

- mobilisation and marketing

This project’s desing helped women with specific queries (related to gender) or with lower literacy rates to reach a knowledge that, had the ICt4D project been designed in a different way, they would most probably have missed.

Philippine Community e-Centers

Telecenters in peri-urban areas. Though in absolute terms there were not much difference in usage rates amongst women and men, difference could be seen in how the telecenters were used and what values they assigned to them. For instance, women used the telecenters as ways to meet people, as ways to socialize. There were also differences in patterns of access and utilization in relation to age, education and income.

Fantsuam’s Zittnet Service — Nigeria’s first Community Wireless Network

To increase female uptake of the Internet, especially in rural areas.

Coverage of signal was not the issue, but hardware and high costs of bandwidth. Still, even if coverage was good, women had to travel to the centers, and this was a barrier for uptake, as also was low literacy levels.

Maybe it’s not about a wireless network, but embedding this project into a wider one aimed to reduce poverty by supporting rural female farmers. Besides, there is a clear preference towards voice communication over written, and SMS over the Internet.

SOS SMS

In distressful situations, women can send an SMS that is received by 5 institutions. Besides reporting of harassment and direct action by the authorities, these messages can be aggregated and thus infer patterns and profiles where harassment and distress are more likely to happen.

Why ICT4D (for women)?

- ICTs can provide access to resources and contribution to income, knowledge, etc.

- Indirect impact of ICT4D and access to income, knowledge, education, etc. on self-confidence and self-esteem. ICT4Ds have an impact on empowerment, in changing relationships, in agency.

- Emergence of new roles (of women).

- Changes in relationships

Why gender evaluation in ICT4D?

- Evidence of change in gender roles and relations can be used for more gender sensitive policies and programmes.

- Evaluations contribute to developing benchmarks and indicators for gender equality in ICT

- Developing capacity in gender evaluation (and gender planning) is a key contributing factor in mainstreaming gender in ICT for development

Q & A

Q: What’s the general procedure for such projects? A: There are mentors that capacitate evaluation facilitators through workshops, and then an evaluation plan is developed together with all the members of the partnership working on the project. Online spaces are created (e.g. with Ning) to support interaction and network creation.

Assumpció Guasch: It’s easier to work about gender evaluation if the promoters — especially governments — of ICT4D projects already have some gender awareness. Another issue is knowing the ICT Sector and the Industry, what’s the legal framework they’re facing. And it is also important knowing what are the technological issues that are crucial in these projects.

Q: How important is the role of capacity building? How is sustainability dealt with in gender projects? A: To be able to have some impact, capacity has to be built. As part of the capacity building strategy, handbooks and toolkits are built so that a certain levels of capacity and impact can be achieved quickly. Empowerment is, arguably, a measure of sustainability, as the more empowered the people the more self-replicable the model. But projects are not that easy to translate from one place to another.

Cecilia Castaño: Besides direct, action and empowerment, a gender focus has also some other derivatives: a sense of listening to “unheard” people, creating community and raising awareness about gender.

Comment: mobiles vs. Internet? People like Barry Wellman state that mobile phones help strengthening the strong ties (e.g. family), while the Internet helps broadening your network of weak ties.

Ismael Peña-López: can the Gender Evaluation Methodology be transposed to other collectives (e.g. immigrants, lower income collectives, etc.) so that to better design ICT4D projects? I guess that in gender-based projects there is a part that is strictly related to gender, but another part that deals with identifying and managing inequality and difference. Inasmuch there is a “managing the difference” issue, I wonder whether some gender-based projects could be just slightly adapted to identify and improve other projects aimed to bride other “differences”: educational, income, etc. Methodology, handbooks and toolkits, etc. could be then split in two parts: identifying, managing and evaluating the differential factor; and then focusing in the specific differential factor: gender, education, age, income, disabilities…

A: Gender is not only man vs. men but is much more complex: education, income, etc. So, it really makes sense to address the gender issue in itself. A gender approach does not mean that the project is focused towards the e-development of women, but just trying to include a new variable in the project. And there’s gender everywhere, so it maybe does not make a lot of sense thinking about “taking gender out” of the equation.

Assumpció Guasch: some projects in Extremadura (Spain) have tried to apply gender methodologies into e.g. age issues. The difference between gender and other issues is the pervasiveness of the former.

More information

10.4 MB)

10.4 MB)