By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 15 January 2019

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: antonio_calleja, decidim, quim_brugue, rosa_borge

No Comments »

Quim Brugué, Universitat de Girona

Participation: what are we talking about?

Participation is not new. We’ve been hearing about this since the 1970s and there already is a boom of citizen participation in the early 1990s. The first decade of 2000s, until 2007, witnesses a quick rise of citizen participation, with a strong support of the Administration. These are years of learning to participate in “good times”. It was an experimental period. There was no consensus of what was the purpose of participation. Many times the issues were not crucial to citizens, but very marginal: no “serious stuff” was shared with the citizen. It generated some not purely legitimate practices where participation was a means to give local administrations or civil society organizations either resources or a public platform were to air their ideologies. This experimentation also led to more focus on the methodology rather than on the issues: people did not want to solve a specific issue but “do participation”.

Experimentation, lots of resources, focus on the instrument rather than on the topic led to some tiredness and disenchantment with citizen participation. This did not last long: the 2008 crisis put a stop to the whole trend.

2011 — 15M Spanish Indignados Movement, Arab Spring, Occupy — was the outburst of a sense of lack of quality democracy. Citizen participation came back to the spotlight, but not on a period of dire crisis. The paradox was that when participation was most needed, lack resources due to the crisis could not meet the needs.

So, what is citizen participation? Many things:

|

| Representative democracy

| Direct democracy

|

| Additive democracy |

Democracy of the moderns: do not trust citizens, trust representative. Risk: “they do not represent us” |

Referendums, polls. Empowerment vs. experience of elder people |

| Deliberative democracy |

Democratize policies: participation, consultation vs. authority, legitimacy |

Democracy of the elder: trust citizens, do not trust representatives. Risk: elitism |

Technology plays a different role in each different approach. While it is not yet clear neither the better technology or methodology nor the impact or degree of improvement, it does seem clear that there is a trend towards empowerment of the citizen. And a thing that has not changed is that every option carries an underlying ideology: while deliberation is about the “we” and about building a solution, polling is about the “I” and winning the preferred option.

Antonio Calleja, Internet Interdisciplinary Institute

Decidim

Especially since 2011 we’ve been witnessing a crisis of representative democracy and a rise of “datacracy”, where who owns more data can affect or even interfere representative democracy and its processes.

Decidim aims at being an alternative to big corporations controlling the platforms that will be used by “datacrats”. Decidim is thought as a political network.

As a political network, Decidim has a community around the platform that deals about strategic and technological issues, also including research, dissemination, etc.

Decidim begins with the strategic plan of the city council of Barcelona in 2016. Initially based on the citizen participation software of Madrid, Cónsul, it was later recoded as a new platform on 2017. New features have been added since.

An important feature is the ability to track what happens with a given proposal by a specific citizen: how it is included in an approved political measure and the degree in which this measure is executed.

(NOTE: case study on Decidim: Peña-López, I. (2017). decidim.barcelona, Spain. Voice or chatter? Case studies. Bengaluru: IT for Change)

Rosa Borge, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

Research project to test the deliberative capacity of several projects that have used Decidim to enable citizen participation. 18 projects were analyzed, choosing first level processes such as strategic or investment plans at the local level.

Decidim has become central in organizing and managing participation processes in municipalities. It is worth noting that the platform was used by municipalities with governments from different parties, and ranging from left to right in terms of ideology.

There does not seem to be a pattern between the number of participants, number of proposals and number of comments to these proposals. The evolution of participation processes varies a lot depending on a wide rage of reasons.

The tool has proven useful to run three dimensions of participatory processes:

- Participation

- Transparency

- Deliberation

The reasons to run participation processes and to do it online are many. Sometimes it is a honest need, sometimes a way to be trendy and get more votes in the coming elections, sometimes it is mandatory by law depending on the kind of policy to be passed. What is clear is that many times there lacks a deep reflection on why and what for developing participation initiatives at the “theoretical” level (purpose, design, limitations, etc.).

The research analyzed the quality of deliberation performing content analysis and according to several indicators like equality in the discourse, reciprocity, justification, reflexiveness, pluralism and diversity, empathy and respect, etc.

Results show that there certainly is a good degree of depth in the discourse and a real debate with pros and cons on the proposals. The dialogue shows almost no effect of echo chambers but, on the contrary, dialogues provide reasoning, proposals or alternatives.

Unfortunately, the debates that take place on the institutional platform are not transposed on other social networking sites like Twitter, were the audience could be bigger and reach a greater range of actors.

PESTEL and DAFO analyses were conducted to better understand the environment and main trends.

On the cons side, there still is a certain lack of commitment from political leaders. On the pros side, online participation attracts new actors to participatory processes that were not the usual suspects of citizen participation.

(NOTE: paper on this research Borge et al. (2018). La participación política a través de la plataforma Decidim: análisis de 11 municipios catalanes. IX Congreso Internacional en Gobierno, Administración y Políticas Públicas GIGAPP. Madrid, 24-27 de septiembre de 2018. Madrid: GIGAPP).

Discussion

Anna Clua: what has been the impact of the digital divide? Have municipalities taken it into account? Rosa Borge: municipalities do not have the resources to measure and seriously address the issue. Notwithstanding, some of them are aware of the issue and thus have made some projects (e.g. training) to try and bridge it during participatory processes.

Manuel Gutiérrez: does online deliberation create more or less discourse fallacies? Rosa Borge: in general, the research has not found many bad practices. On the contrary, quality of the debate was high according to the indicators chosen. Of course the methodology is arguable and there were some methodological issues that are worth being reviewed.

Quim Brugué: can we deliberate on everything? Should we deliberate when the government has already decided on a given issue? What for? Rosa Borge: of course if the decision is already made, it may not make a lot of sense. Notwithstanding, most dedicions are not “totally” made and all comments and shades of meaning poured on the platform are taken into account by decision-makers — as stated by officials and politicians during the research.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 16 November 2018

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: albert_royo, artur_serra, edemocracybcn, robert_bjarnason, robert_krimmer, simona_levi

No Comments »

Experts and activists

chaired by Albert Royo

Why Voting Technology is Used and How it Affects Democracy

Robert Krimmer, Professor of e-Governance, Tallinn University of Technology, Ragnar Nurkse School of Innovation and Governance

Estonia is the only country in the world introducing e-voting universally, at all levels. To address:

- Decreasing voting turnout.

- Increasing distance between rules and ruled.

- Increased citizen mobility (globalisation)

Governments say they want to engage in a continuous dialogue with citizens, but are quite often reluctant to actually do it. In the same train of thought, citizens also want such dialogue, but cannot vote just everything (quick democracy) and, most especially, cannot be informed on just everything (thin democracy).

e-Democracy will transform democracy and challenge representation, but it can also offer more participation possibilities.

e-Voting strengthens secrecy and security in comparison to traditional voting, not the other way round.

Democracy as citizens’ surveillance on their institutions

Simona Levi, Founder of XNet

More than e-democracy we should be talking about distributed governance.

Net-neutrality is a must if we do really want that democracy and technology can enhance each other.

Democracy and privacy to correct the asymmetry of power between citizens and institutions. Anonymity and encryption are a must to protect communications. Going against this is highly un-democratic.

Public money used to create content and innovation should not be privatized. This includes algorithmic democracy or algorithmic decision-making.

We must defend technology, not only use it. And transparency and participation must to be at the same level. We want efficient institutions.

Catalonia, a Lab for Digital Citizenship

Artur Serra, Deputy Director of i2cat

The Internet is helping to change our political systems. The Internet works under a certain distributed architecture, and this embedded technological model is slowly but surely altering the democratic institutions’ model.

On the other side, our political systems are also changing the Internet: fake news, firewalls, etc.

Can we think of an open living lab, made up of cultural and citizen platforms, digital rights activists, local structures of digital facilitation, research centres, lawyers, etc.

Citizen participation and digital tools for upgrading democracy in Iceland and beyond

Róbert Bjarnason, CEO and co-founder of Citizens Foundation

For there to be trust, citizens must have a strong voice in policy-making.

- Your Priorities: policy crowdsourcing to build trust between citizens and civil servants with idea generation and debate.

- Active Voting: participatory budgeting.

- Active Citizen: empower citizens with artificial intelligence.

Citizens need to be “rewarded”, show that the government listens and does things — not only talking about things. Good communication is key to success.

There is a danger of privatization in the evolution of democracy online. Participation infrastructure has to be kept public.

Discussion

Simona Levi: traceability of participation is a must. What happened with my contribution? Where did it go? Why was not it accepted?

Artur Serra: where does social innovation come from? Does it come from institutions or from the margins? How do we gather these initiatives? Do we care about citizen labs?

Robert Bjarnasson: it is not about tools, but about innovation, about opening processes. Start with something tangible, something small, and move from there.

Artur Serra: technology is not a tool, technology is a culture. The new tool is the embodiment of a new culture. We have to learn to think different. If we treat participation as consumerism, we are failing.

eDemocracy: Digital Rights and Responsibilities (2018)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 16 November 2018

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: arnau_mata, carles_agusti, edemocracybcn, jennifer_layden, joana_barbany, jordi_puiggali

No Comments »

Panel of stakeholders and tech companies

chaired by Joana Barbany

Municipalities and technology: more political participation?

Cllr. Jennifer Layden, Convenor for Equalities and Human Rights of the Glasgow City Council

Being involved in new media and social media enables administrations to engage with citizens.

There still is the challenge how technology can help to bring better outcomes, to bring increased access to democracy and participation. So far increased access is quite a success, as many people that cannot attend face-to-face meetings do participate online.

Enabling access to participation through online technologies should not be in detriment of excluding people for just the opposite reason: they cannot use online tools.

Working with local communities with participatory budgeting.

Technology and participation, one more step towards democratic pedagogy

Arnau Mata, tinent d’alcalde de Comunicació, Participació Ciutadana i Sistemes TIC, i portaveu de l’Ajuntament de Sant Vicenç dels Horts

The general context of political corruption is affecting all the institutions, regardless whether they or their members are corrupt or not. This is putting a stress on daily governance.

Some participatory processes where put to work, to let citizens have their say, and enable new ways so that institutions could speak with the citizens.

They are using Decidim, Barcelona City Council’s participatory platform.

Online participation allows monitoring of participatory processes, helps people to participate, empowers minorities in the public agenda, legitimates civic organisations, etc.

Open government and citizen participation channels in the digital era

Carles Agustí, Open Government Director at the Barcelona Provincial Council

Unlike preceding times, now citizens have lots of information, usually much more than governments themselves. Adaptation to this new reality is compulsory.

Open Government is the answer to the demands of change of the people in the way to do governance and politics. But it is not only a mere website, but a whole new strategy, a deep cultural change.

Technology is absolutely changing the landscape:

- Open data would simply not exist without technology.

- Civic platforms can better organize with technology.

- e-Participation opens new channels, ways and methodologies for participation.

- And, last but not least, more and different individual citizens can gather thanks to technology.

It is important to acknowledge that data have a lot of public value when they become open as open data. And that it is not only about giving data away but also about listening to citizens.

On-line voting: a security challenge

Jordi Puiggalí, Head of Research and Security Department, Scytl

There are no secure channels: it’s security measures that you implement that make voting secure. This includes on-site voting or postal voting.

Cryptographic protocols can guarantee privacy and integrity of voting processes.

Cryptography also allows to audit voting processes.

Discussion

Jordi Puiggalí: Blockchain can provide identity, but not integrity nor privacy.

Arnau Mata: the best way to convince people to participate is showing that it does work, that the government cares about what is being said and applies the general agreements.

eDemocracy: Digital Rights and Responsibilities (2018)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 October 2018

Main categories: Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: ideas4change, mara_balestrini, redparticipacion2018

No Comments »

Mara Balestrini.

Beyond the transparency portal: citizen data and the right to contribute

We assume that information only goes one way: from the Administration to the citizen. This assumption is not valid anymore. Citizens produce lots of data that could be used to leverage change. We should acknowledge the right of citizens to produce data, not only to receive data.

What can citizen-generated data do?

How to do it? We need to plan ahead a strategy of participation, and begin with the things people care:

- Identify the issue and the people that care: people directly interested in the issue, altruistic people that want to help, communities of practice of people that work in the field, and communities of interest of people that want things to happen in a given field.

- Frame the issue. It is necessary to link the abstract (“mobility in the city”) with the concrete (“where can I park my bike”). The Administration usually cares about the abstract, while the citizen cares about specific issues.

- Design a participatory project. It is crucial to avoid the creation of an elite of participation.

- Deploy it.

- Orchestrate it. Awareness raising activities so that more people join the project. Though not only by “voting”, but by contributing with what they can/know: helping to define, analysing, explaining, etc.

- Assess and evaluate the outcome. And include the creation of an infrastructure of participation that remains after the process is over.

Case of the Plaça del Sol in Barcelona, to approach the problem of noise in the square. There are huge amounts of noise, which cannot be measured and, in fact, “no one is doing anything wrong”, but it is the aggregation of small noises that creates discomfort in the neighbourhood.

A project was created to measure noise by citizens, aggregate public open data and raise awareness on the issue by showing evidence of the problem. Once the problem was actually measured, citizen assemblies were made to collectively find a solution.

Some outcomes of the project:

- Open and shared data.

- Skills and capacity. The more complex the tools, the more excluding will be — unless we build capacity around them.

- Co-created solutions.

- New open technologies and knowledge.

- New networks and social capital. New politics is about creating emerging communities out of a citizen issue.

Of course, not only should citizens have the right to generate data, but have ownership over these data, to have governance over data.

How about co-create license to share citizen data?

- TRIEM is a study that uses collective intelligence mechanisms to co-design licenses to access and use our data.

- DECODE is creating an open data commons.

- Salus.coop is a citizen cooperative of health data for science.

The Administration should foster the creation of new infrastructures: legal infrastructures, that regulate citizen data, new institutions (such as the recognition the role of citizens in creating and sharing public data), etc.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 29 September 2018

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: enrique_rodriguez, ricard_espelt, technopolitics

No Comments »

¿Economía alternativa o tecnopolítica? Activismo desde el consumo cooperativo de productos agroecológicos (article)

¿Economía alternativa o tecnopolítica? Activismo desde el consumo cooperativo de productos agroecológicos (article)Ricard Espelt, Enrique Rodríguez and I have just published a new article, ¿Economía alternativa o tecnopolítica? Activismo desde el consumo cooperativo de productos agroecológicos [Alternative economics or technopolitics. Activism from agroecological products cooperative consumption] which analyses the relationship between technopolitics and the cooperative movement. Our hypothesis is that some emerging cooperatives go beyond the mere practice of cooperativism for production or consumption, and engage or even are driven by political values. Our findings only partially support this hypothesis, but allow us to characterise three types of cooperatives according to these political values and activism, which we found quite interesting.

Expanded summary

Agroecological cooperativism is made up by an inter-cooperation network articulated by producers and consumer groups that promotes the acquisition of agroecological products in the context of the Social and Solidarity Economy (Martín-Mayor et al., 2017). At the same time, as part of the anti-globalisation and territorial defense movement, it has political resolution (Vivas, 2010). In this sense, it frames its activity as a response to the homogeneity of global food chains (Mauleón, 2009; Khoury, 2014) and promotes a recovery of the «identity of the sites». This re-appropriation purpose is expressed -especially- in the social movements that emerged during 2011 that, according to Harvey (2012), link with the fight against capitalism and the demand for a collective management of common goods and resources. Across the area of Barcelona, where the map of consumer cooperatives is well defined (Espelt et al., 2015), it has been registered an increase of these kind of organizations during the 15M or the Spanish “Indignados” movement in 2011.

As embedded in the era of the Network Society and the expansion of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), this article studies the correlation between agroecological consumer groups, as an instrument to promote an alternative economy, and social movements, as the space where technopolitics develop (Toret, 2013). That is, this article aims to corroborate whether agroecological cooperativism, which emerged in the late 20th century -and grew with remarkable strength during the second decade of the 21st century- and the profound crisis of legitimacy of the democratic institutions, with a rising participation in citizen extra-representative and extra-institutional movements, is connected.

This article has a double goal. On the one hand, to assess the existing relation between consumer and cooperative groups and the 15M movement and their ideological similarities, as selfmanaged movements that aim for social and political transformation. On the other hand, if applies, to study how this relation is shaped.

The main hypothesis of our research is that nowadays agroecological cooperativism possesses an acute activism component, which is why it is reasonable to predict a relative involvement of this activist cooperativism in movements such as 15M. However, former literature has explained and described the 15M movement as a form of activism that eminently operates outside the institutions and through a network organization. From that point on, a second hypothesis is formulated, proposing that activist cooperativism participation occurs individually, rather than collectively and/or institutionally. That is, it is possible to identify overlaps between activists that take part both in cooperatives and social movements such as 15M, but it is not reasonable to foresee a relevant level of involvement of cooperatives, as collectives, in this movement.

In order to respond to the hypothesis, a questionnaire comprising two sets of questions has been designed. A first set aims to determine the level of accomplishment based on the SSE criteria. A second set of questions focuses on the correlation between the studied organizations and the 15M movement, and the relevance of ICT in their organization. Semi-structured interviews were sent between February 2015 and March 2016 with a sample of 44 groups and allowed us to gather information regarding the origins, motivation and functioning of each of them. The questionnaire about the relation between the groups and the 15M movement was sent between December 2015 and March 2016, and 37 responses were collected. Thus, the 37 groups that have completed both questionnaires and the semi-structured interview will be considered the sample for this research.

In order to assess the accomplishment level of the variables corresponding to each of the aspects of the Social Solidarity Economy and the relation of the organizations with the 15M movements, we have performed arithmetic measurements for each of the variables studied. To evaluate the performance of the formulated hypothesis we have applied a correlation and a factorial analysis upon the studied variables (Commitment, Ideology, Technology, Group Involvement and Individual Involvement) to quantify the existing association between variables (correlation) and to identify the latent existing relation between them (factorial), with the goal of gathering additional information that has allowed us to interpret the results of the individual classification (nonhierarchical segmentation). Once the groups have been obtained, significant differences between segments have been determined through a variance analysis (ANOVA).

The results of our research show that consumer groups are part of a larger group of organizations that conform the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE), which, among others, values the promotion of spaces in which democratic participation is emphasised. If we constrain our analysis to 2011, just in a few cases the creation of new groups can be drawn from the influence of 15M. However, the entities created that year recognise the movement as an agent of change for the individuals in their condition of activists. At the same time, this research allowed us to determine three types of organizations: the traditional cooperative, which shows a low level of social commitment and a moderate level of individual participation, and that barely embraces ICT; the network cooperative, which adds social commitment and ICT usage; and the activist cooperative, which presents a greater group and individual involvement.

Despite the sample is limited in quantitative terms, the results confirm our hypothesis, which is to say, that cooperativism has a strong activist component. This finding points in the same direction with what Cantijoch (2009), Christensen (2011), Anduiza et al. (2014) or Peña-López et al. (2014) have expressed with regards to a strong (and even rising) tendency in extra-representative and extra-institutional practices when it comes to take part in political participation or citizen activism. On the other hand, despite the classification of the groups in traditional, network and activist cooperatives, we dare to say that their relation with the 15M movement must be, therefore, exogenous, depending on a non-identified variable, which is highly probable individual and not consubstantial with consumer cooperativism. That is to say, one doesn’t affiliate to a cooperative – as it’s the case as well with political parties, labor unions or NGOs- in order to achieve other political goals, but rather that one’s active participation in cooperativism constitutes the techno-political action by itself.

Downloads:

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 10 September 2018

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

No Comments »

This is a three-part article entitled Fostering non-formal and informal democratic participation. From mass democracy to the networks of democracy.

The first part deals with Man-mass and post-democracy and how democracy seems not to be maturing at all, or even going backwards due to lack of democratic culture and education. The second one deals with the Digital revolution and technopolitics and reflects about how the digital revolution might be an opportunity not only to recover but to update and transform democracy. This third part speaks about what kind of Infrastructures for non-formal and informal democratic participation could be put in place.

Democratic participation happens in a planned and structured way: elections, sessions in the representation chambers, etc. they have their place in time and an internal order for their development.

Non-formal participation lacks the first feature: although it has an internal structure —provided often by institutions, but increasingly by citizens without an entity behind it— it takes place ad-hoc to respond quickly to a specific issue.

Informal participation, finally, is one that is neither planned nor does it have an internal structure determined as a spontaneous manifestation or assembly, or many debates in spaces such as social networks.

The general objective of a policy to promote infrastructures for non-formal and informal democratic participation is to identify actors, facilitate spaces and provide instruments that enrich the non-formal and informal democratic practice so that it achieves its objectives, either directly or through channeling action at some point towards a democratic institution.

- Actors: in addition to people who may have an interest or knowledge in a given policy, articulate the participation and active intervention of intermediaries (prescribers, experts, representatives), facilitators (experts in making happen democratic participation actions) and infomediaries (experts in the treatment of data and information for public decision-making).

- Spaces: create the conditions so that the actors can work together, either coinciding in time and space as with other “spaces”, facilitating especially the conditions of participation, mediation strategies, channels and codes, weaving the network and explaining its operation.

- Instruments: methodologies, operating regulations, technological support (digital or analogue) for information, communication, decision-making and return.

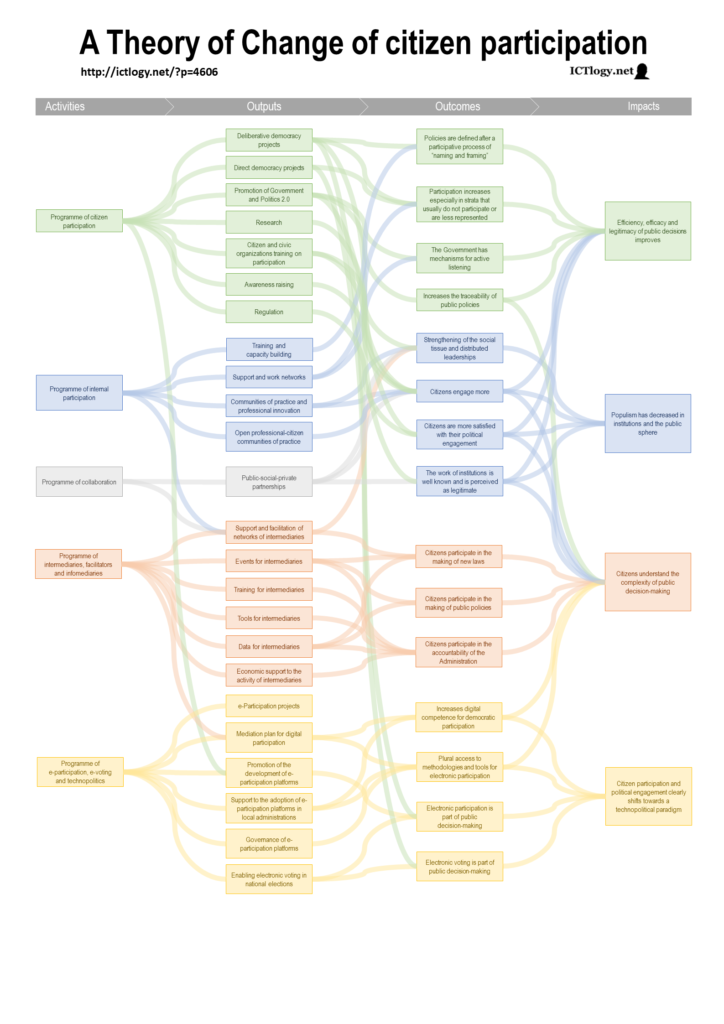

For the deployment of this policy to promote infrastructures for non-formal and informal democratic participation we propose six axes or priority action programs:

- Deliberative participation program: to promote and improve projects on deliberative democracy, government 2.0, an appropriate regulatory framework for citizen participation, and awareness of the importance of this instrument through training, research and dissemination.

- Program of electoral participation and direct democracy: promote and/or improve electoral processes to increase the legitimacy of formal participation processes, as well as projects on direct democracy consisting of the return of sovereignty to the citizen; raise awareness about the importance of these instruments through research and dissemination.

- Internal participation program: work towards a transformation of how the Administration understands participation, collaboration and cooperation within the institutions as well as in its relationship with citizens, through training and support networks and work, communities of professional innovation practice and open communities of practice between public professionals and citizens.

- Collaboration program: with the objective of standardizing and normalizing public-social-private consortiums and innovation initiatives according to the quadruple helix model; or, to put it another way, to work for the planning and structuring of non-formal and informal initiatives of democratic participation for its scaling and replication.

- Intermediaries, facilitators and infomediaries program: to contribute to the growth and consolidation of a trained and/or professionalized sector in the field of participation, in order to achieve the highest quality of participatory practices and projects, providing the sector and citizens involved with knowledge, instruments, technological tools or resources in general.

- E-participation, electronic voting and technopolitics program: accelerate the adoption of ICT in the field of participation, thus contributing to facilitate and standardize electronic participation, electronic voting, electronic government and electronic democracy in general, at the same time transforming the paradigm behind citizen practices based mainly on passive or merely responsive actors towards a technopolitical paradigm based on active, empowered and networked actors.

We can see a graphic representation of these six programs in the Theory of Change of Citizen Participation that appears below.

In it we can see how the programs become products or political actions that, in turn, have expected results (measurable according to the established objectives and indicators) and that, according to the theory, will lead to an impact, understood as a change in social behavior —or a latent variable impossible to measure.

As we have started saying, the expected impact wants to go far beyond the improvement of efficiency, effectiveness and legitimacy of the democratic system, although this is the first desired impact, of course.

On the one hand, one should aim at fighting populism, fighting the simplification of politics and the manipulation of citizens working to improve the social fabric, information and the involvement of citizens in public issues.

This participation, moreover, is not merely quantitative but qualitative, given that we aspire to explain the complexity of the challenges of public decision-making and management with the concurrence of citizens in the design and evaluation of them.

We achieve this, besides reinforcing the traditional channels of institutional participation, by encouraging non-formal and informal participation initiatives, establishing or re-establishing broken bridges between institutions and citizens but, above all, doing it on an equal footing, sharing sovereignties … and sharing the resolution of the problems associated with the responsibility that comes with enjoying such sovereignty, both personal and collective.