By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 19 September 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings

Other tags: 11aecpa, gonzalo_caballero, ilke_toygur, marta_parades, teresa_mata_lopez

No Comments »

¿En qué medida la actual crisis económica española está conduciendo a una crisis de la democracia? El propósito de este grupo de trabajo sería discutir los efectos de la crisis a partir de la tradicional diferenciación de las percepciones políticas de los españoles en las tres dimensiones de legitimidad, descontento político y desafección, con especial atención a la desafección y sus distintos componentes. De modo específico planteamos que, en el contexto de la presente crisis, la evolución de la desafección puede estar bifurcándose, de tal modo que aumenta en algunos de sus componentes y entre categorías sociales con menos recursos; al mismo tiempo que disminuye de la mano de otros indicadores como el interés por la política, entre otros. Esta última tendencia estaría alentando un mayor número de ciudadanos críticos, más implicados y exigentes con el ámbito de lo político; pero, en definitiva también, menos desafectos.

Este grupo reúne trabajos que analicen tanto la evolución longitudinal de estas tres dimensiones y sus distintos indicadores, como su impacto en distintos subgrupos de población, prestando especial atención a los jóvenes, los desempleados y los habitantes de algunas comunidades autónomas. Existe un acuerdo bastante generalizado de que la crisis económica ha tenido efectos claramente diferenciados en distintos grupos sociales, así como por territorios. Por ello, el grupo de trabajo quiere reunir propuestas sobre la percepción y la implicación con la democracia entre estos distintos grupos. Ello debería permitirnos ofrecer una visión de conjunto que esté, sin embargo, basada en sus distintas tendencias.

Great Recession, institutional crisis and social change in Spain: institutional analysis and empirical findings.

Gonzalo Caballero

The paper analyses the dynamics of institutional change in the Spanish society.

Reference: Douglass North and institutional design.

Institutions as rules or institutions as equilibriums of individual pressures?

In recent years, institutional design and change has been approached as endogenous. In the case of Spain, the institutional equilibrium during the Francoism has developed into a new institutional equilibrium of the Democracy. This evolution happened in Spain specially during the 1960’s were quasi-parameters were developed and which came forward once the dictator was dead and the regime changed. Shift from self-destructing institutions of the early Francoism to the self-reinforcing institutions of the democracy.

Despite the institutional change, there still is a certain institutional deficit. And then comes the crisis: first recession in 2008-2009, a very slight recovery, and a second recession in 2011-2013. The characteristics are highest unemployment rates, general strikes, social movements and, in the end, political dissatisfaction.

Methodology: take the political trust (CIS) and compare it with the unemployment rate, and controlled by the existence of elections. The results show that when unemployment grows, political trust falls. The existence of elections, though, highly increases political trust.

Conclusion: there is a risk that a long crisis and its negative impact on employment can have a negative impact on political trust and, thus, reduce the legitimacy of the institutions.

Economic crisis and democracy and Spain: legitimacy, dissatisfaction and disaffection.

Ilke Toygur

- Political support/democratic legitimacy was as widespread in Spain as in any Western Europe countries.

- Political support has remained solid in the period in spite of sometimes turbulent circumstances (terrorism and violence, military coups, etc.)

- High levels of political dissatisfaction/discontent has abounded in the period, but never led to a decline in support of democracy or to birth of relevant anti-system parties.

Two dimensions of disaffection: institutional disaffection and disengagement.

Questions:

- Do the previous questions still apply in Spain?

- Can trust be put back into the system or is the system already spoiled? Will the political system be granted support ever again?

Hypotheses:

- There is no direct relationship between legitimacy and discontent.

- The discontent is not a threat to the system.

- Economic crisis is affecting the citizens in different ways.

Time series analysis for setting:

- The association between legitimacy, dissatisfaction and disaffection.

- Their dependence on economic and political facts during the last three decades.

Dependent variables (CIS): legitimacy and satisfaction. Independent: government performance, party in government, levels of education, terrorism, corruption, ideological positioning.

Unemployment negatively affects legitimacy.

Who are the citizens? A typology

|

|

Trust

|

No trust

|

|

Interest

|

Cives

|

Critical

|

|

No Interest

|

Deferential

|

Disaffected

|

Conclusions:

- Even if political discontent and country is governed by bad policies, legitimacy is not affected.

- Citizens blame the government both for the situation of economy and austerity policies.

- Economic crisis is bringing a political crisis.

- Among those disaffected, what is the relationship between their diffidence toward institutions and their support for the political system? Are they angry with institutions but still believe that the system, as a whole, is a good thing?

The political effects of the economic crisis in its territorial dimension: legitimacy, dissatisfaction and political disaffection in times of crisis.

Teresa Mata López, Marta Paradés

Taking into account that the “autonomías” have been key for the consolidation of democracy in Spain, how has political disaffection been affected by the crisis in the different autonomies?

Hypotheses:

- Legitimacy of the system not related with satisfaction of the economy.

- Satisfaction with the system relate with the performance of institutions.

The support to the autonomic model changes along time but differs depending on the territory.

There is a strong relationship between the economic situation of Spain and the legitimacy of the democratic system. But, when the crisis becomes deeper, the significance of the correlation is weaker.

Conclusions:

- The crisis deepens the impact of former changes that were already in place.

- There is a positive relationship between the valuations of the economic situation and the legitimacy of the autonomic state.

- The relationship between the economic valuation and satisfaction with the performance of the autonomic system “disappears” with the crisis.

- There are changes between different territories due to ideology and identity.

XI Congreso de la AECPA (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 19 September 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings

Other tags: 11aecpa, miguel_cainzos_lopez, natascia_mattucci

No Comments »

Los gobiernos que se enfrentan a las urnas en los últimos años lo hacen en un contexto económico muy adverso. Desde la irrupción de la crisis, casi 7 de cada 10 gobiernos europeos no han conseguido mantenerse en el poder. El objetivo de este grupo de trabajo es discutir nuevas investigaciones en curso sobre las elecciones tanto en España (locales, autonómicas y generales) como a nivel comparado (Europa u otras democracias desarrolladas) que han tenido lugar desde el inicio de la recesión. El grupo de trabajo está particularmente interesado en analizar cómo el actual contexto económico ha afectado al comportamiento electoral de los ciudadanos (nivel de participación, voto al gobierno, ascenso de partidos antisistema, etc.) como en sus actitudes políticas. No obstante, también seremos receptivos a trabajos que, aunque no traten directamente la economía como un elemento central, analicen el comportamiento electoral tanto en España como en otras democracias desarrolladas a en los últimos años.

Vote intention in Spain 1978-2013. A Second Transition towards extra-representative politics?

Ismael Peña-López

Downloads

A case of “direct representative democracy”? The Five Stars Movement between the mith of immediacy and the challenge of persistence in the institutions.

Natascia Mattucci.

The Movement 5 Stelle (M5S) got 25% in Italy when most of people used to vote only to two parties. The M5S is not an extra-representative movement: it actually is against the system, but it is also present inside the institutions, to change the system from within.

Most people tag the M5S as an anti-politics movement, populist. But, is it? How does political representation change after M5S breaks bipolarism and becomes the most voted force?

There is a strong anti-politics rhetoric, based on the dilettante politician that “does not need to know about politics”, that does not have to be a professional of politics. Anti-politics is a radical criticism of the professional politician: the politician should be someone that has (another) a job. The politician is a spokesman or a loudspeaker, not a representative. Anti-politics aims at a “repersonalization” of politics, re-establishing a direct bound between the spokesman and the people, who controls and decides.

Politicians, if not representatives but spokesmen, then they have a mandate to translate what the people wants to the parliament. They cannot decide on their own: they just have to vote what the people voted. This has a problem as the representative then lacks its general vision for the common good. If the politician cannot infer from what is being discussed what is best for everyone and vote in consequence, then legitimacy is broken.

The M5S only used social media for their information and communications and promote that citizens do alike. Meetups, blogs, Twitter, etc. are tools that break top-down communication and eliminate the intermediation of mass media – and the biases and censorships that those add.

The problem is inner democracy of the movement: the founders of the movement own the platforms (e.g. the main blog) and the brands. But the thing is that people have embraced the movement because it represents a disruption in Italian politics.

Unemployment and vote. Does unemployment affect the voting experience?

Miguel Cainzos López

- Does the personal experience of unemployment electoral participation?

- Do unemployed people participate differently?

Analyzed the Spanish general elections from 1979 to 2011.

And, briefly put, it seems that unemployment affects very little the sense of one’s vote. But it does have a small negative effect over participation.

The Spanish Context

- Always a lot of unemployment, with most elections with unemployment above 15%.

- Seven big legal reforms of the job market plus a few dozen of minor reforms.

- Unemployment perceived as a major problem by the citizens. The problem is relevant and visible.

- It is characteristic from Spaniards that citizens strongly demand from the State to guarantee a job for everyone.

Hypotheses

- H1: Apathy. Unemployed people are disaffected in general and with politics in particular and, hence, they will vote less.

- H2: Generalized punishment. Voters will reward or punish the government according to their performance. Thus, unemployed voters will punish the government whatever its color, or they will not vote (punish the government without rewarding other parties).

- H3: Ownership of the topic. The party that is perceived as more competent or promotes better policies on the topic, they will “own” the issue. Unemployed people will vote for the “owner” of the issue. The PSOE owned the issue during the 1980’s and, after the 1993-1994 crisis, the PP became the owner until 2011.

- H4: Punishment conditioned to the ideological affinity. Everyone will vote to the party that better fits their ideology. Only unemployed voters that are ideologically near to the party in the government will actually “change” their vote (and punish the government) by either voting another party or just not voting.

- H5: Punishment based on the politization of the personal experience by the left-wing voters. Only left-wing voters will politicize their experience with unemployment and thus blame the government for their economical situation.

Results

Apathy seems confirmed as people tend to vote less when unemployed.

In 1986, left-wing employees did punish the socialist government. The hypothesis of ownership could also apply in 1986. In 2004 (conservative party in office) the logic seems the reverse.

But, all in all, apathy is what prevails.

XI Congreso de la AECPA (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 September 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings

Other tags: 11aecpa, andres_cernadas, eva_alfama, joaquin_martin, jorge_luis_salcedo, juan_medina, luca_chao_perez

2 Comments »

The development of open government initiatives in a number of countries around the world has highlighted the need to establish the means by which all people without exception can benefit from the potential of these initiatives. The risk of a permanent digital divide whereby a portion of the population may remain marginalized from access to the Information Technology and Communication (ICT) has raised concerns (Geneva and Tunis in 2003 and 2005 respectively), and obviously as the open government relies on the use of ICT, it should be developed in a context in which to ensure equal opportunities in access to the entire population. More broadly, the open government expresses a new model of interaction between government and citizens (new citizenship status).Digital citizenship and e-inclusion strategies are therefore inseparable aspects of the development of open government, not only because this is strictly instrumental (open data), from the inside out, from e-government or e-government, but moreover, as the open government requires promote citizen participation in the design and implementation of policies and the provision of public services by opening processes (open process) and the use of social networks and platforms for citizen participation (Ramirez-Alujas, 2012: 20), favoring the open action to improve regulatory proposals submitted by public authorities (Campos and Silvan, 2012: 70).

Digital Citizenship: for every age? Digital inclusion strategies and use of ICTs in different age segments in elderly people in Spain.

Eva Alfama Guillén, Jorge Luís Salcedo Maldonado

Questions:

To what extent policies addressed to elderly people have an ICT component?

- They provide infrastructure.

- They foster digital literacy and development of digital skills.

- Use ICTs to promote wellbeing and participation of elderly people.

Data from 8 municipalities in Spain.

Hypotheses:

- Need of public policies for e-inclusion for the elderly people more positive, comprehensive and participatory, which promote active aging and the strengthening of autonomy and empowerment.

- Key role of ICTs, that can foster autonomy and empowerment of elderly people of make them more vulnerable before digital exclusion.

Users are tech savvy when it comes to mobile telephony, but not about being online.

Intervention levels:

- Participation: low.

- Social promotion: medium.

- Community action: punctual.

- Social services on primary health care: punctual.

Policy makers promote the use of ICTs to connect different generations.

Important focus on tele-assistance.

Fields of intervention with elderly people and ICTs:

- Digital literacy

- Empowerment , autonomy, tele-assistance.

Elderly people do not identify themselves as elderly people: want to be considered as active and participative citizens.

Conclusions:

- Digital inclusion for elderly people very marginal.

- Though these policies address very hot issues.

- Need for more commitment and resources.

An open and transparent government in Spanish municipalities: the case of Quart de Poblet.

Joaquín Martín Cubas, Juan Medina Cobo.

The IRIA report provides evidence that the degree of implementation of ICTs in Spanish municipalities is quite good, both in terms of infrastructure and public services. But the Orange report states that even if infrastructures and services are OK, uptake is not, mainly because of matters of accessibility and usability.

Quart is a small municipality in the province of Valencia. It has a long tradition of participation.

The DIEGO (Digital Inclusive e-Government) project (with funding from the European Commission) was used to create a platform – QuarTIC – through which citizens (especially elderly people) can access e-government services.

The SEED platform aims at improving accessibility and usability of public e-services.

It is worth noting that the municipality needs not develop a lot of technology or infrastructures: citizens are already online at social networking sites. The municipality should be able to be where the citizens are, and engage in a conversation with them.

Now the local government Is adapting the IREKIA (Basque Government’s) open source open government platform to develop their own open government strategy. This strategy, as it has been said before, aims not at substituting but complementing the strategy addressed to being on different social networking sites besides the citizens.

The application of ICTs in the field of Health Care: the case of Spain and Cuba

Luca Chao Pérez, Andrés Cernadas Ramos.

- What is the impact of the Internet on the health system?

- In what applications does it materialize?

- What factors are fostering the change?

- What strategic lines and public programmes are being profiled?

- What should be the role of R+D in Health?

In the field of e-Health, the Internet has meant:

- The democratization of information. But, what quality of information?

- But a lack of communication, lack of interaction.

In Cuba this is a little bit different in relationship with Spain. The INFOMED network puts in contact professionals that work in remote areas, sharing information, interacting among themselves… and also providing e-Health services to their patients.

That is, in Cuba, the application of ICTs in Cuba has been centered in the professional, while in Spain and most Europe the model is more citizen-centered, aiming at empowering the e-patient so that they can manage their own health.

- Are we heading towards a new model of patient: the e-patient?

- Will more information and more empowerment change the kind of health interventions?

- Are we assessing e-Health initiatives to be able to tell the impact of the policies? The cost-benefit analysis?

XI Congreso de la AECPA (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 25 August 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: e-democracy, social_movements

No Comments »

The following paragraphs do not intend to present an idea particularly new, although I think it is pertinent to say that they seek to revisit an old idea under a new context.

On the other hand, this is more an intellectual exercise — or even a speculation — rather than an academic proposition. However, it is fair to acknowledge that this exercise does not appear out of the blue. On the contrary, it is firmly based on two recently published works and the respective bibliographies that support them:

- Casual Politics: From slacktivism to emergent movements and pattern recognition (bibliography).

- Spanish Indignados and the evolution of 15M: towards networked para-institutions (bibliography).

Finally, although this discussion has been cooking in the oven for the last few months, I can not leave unsaid that Daniel Innerarity’s latest op-ed — ¿El final de los partidos? [The end of parties?] — has been the final trigger. The article — a highly recommended reading — goes on to state that although the world has changed, the institutions of democracy (governments, parliaments, political parties, unions, nonprofits, etc.) are still the best way we have to organize our lives in society. And that these institutions being reformed, but in essence those are the ones we have and the ones we should be keeping.

Institutions and democracy

Les us simplify as much as possible — with the consequent risk to fall into inaccuracies, generalizations and biases — what is a liberal democracy.

Since policy is no longer the management of the polis, citizenship has been alienated from the exercise of directly and personally ruling public affairs. This is no answer to no plan hatched in the dark to uptake power, but mainly responds to reasons of efficiency: the polis has become a county, a region, a state, a global world that requires full-time leaders, professionals that can manage the enormous complexity of politics and that, of course, serve all citizens and respond to them and their needs. No one can afford devoting themselves to managing public affairs and, at the same time, managing personal matters and earning their livelihoods. At least not without the slaves who had our Greek ancestors (some of our contemporary representatives actually have someone working for them, or just neglect public affairs, but this is another matter).

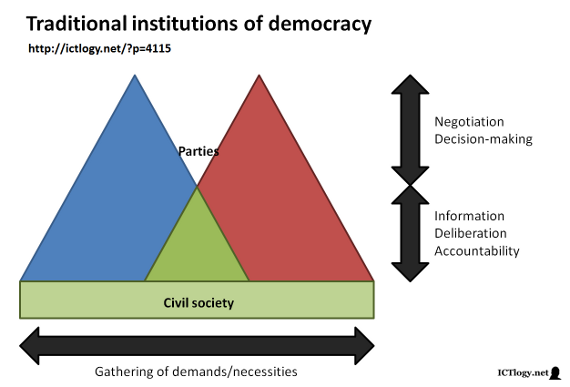

We have created, thus, institutions that represent us politically and work for everyone. At the lowest level of those institutions (e.g. political parties or labour unions) many citizens participate (joining, sympathizing, collaborating) to gather information on the needs and demands of their peer citizens, as well as deliberating on the various possible solutions.

At another level, a few representatives (governments, parliaments) are responsible for making decisions, after having negotiated the wills of the various groups represented. At the end of the cycle, this level ensures accountability of the decisions made before the lower level.

The general population, given the difficulty of being informed and engaged, remains outside the whole process and only follows it remotely through the press, political propaganda and punctual moments of participation through the ballot box.

Crisis of institutions

There are at least four reasons why current political institutions have seen their legitimacy diminishing in the process of representative (or institutional) democracy:

- Because the professionalization of their boards has become not a means but an end in itself. Staying on the job happens to be the goal of many in office, getting out of line of what should be their genuine purpose: to serve the citizens they represent. This deviation or sheer abandonment of the original mission of the institutions, of course, has happened at the expense of the legitimacy and the gradual withdrawal of citizenship.

- This professionalization has crowded out from the foundations of the institutions those citizens who saw participation as a vocation of service and not as a professional vocation. This expulsion may have been active or reactive, but the results have been clear: thinning of the bases and withdrawal (again) of the bulk of the citizenry.

- The increasing complexity of politics, together with the professionalization and the brain drain of the institutions has resulted in the worst of situations: trivialization and playing down of the complex, simplifying the political message and its consequent radicalization of ideas. The political debate becomes meager, addressed to media, puerile, rather than strengthening deliberation and seeking learning in the democratic process. In the absence of political pedagogy, behold disaffection.

- Last but not least, many of the previously mentioned issues may not have a solution, but they could in deed have a strong contribution thanks to the new Information and Communication Technologies (information and communication: how often we forget the meaning of the acronym ICT). There are many things that ICT could help on: encourage participation and engagement of talent, transparency and accountability, dialogue and debate. If they are not a magic solution, their negation itself is a clear statement of principles: although the use of ICTs may have great potential in all areas of politics, we have no intention of putting them into practice and realize this potential. More disaffection, especially from the ones who could and would participate.

Consequences?

On the one hand, the thinning of the bases of the institutions, especially those closest to the citizenry (parties, unions). On the other hand, the shift of information and accountability “upwards”: the same ones that negotiate and make decisions are the same ones that are informed about what is “necessary” or “convenient” being done, and are also the same ones that are accountable amongst themselves.

The result is a growing disconnect with the society due to the shrinking of the social bases and the lack of in-depth, “vertical”, technical and political paths of the implemented policies. Deliberation is not only absent but even avoided. Without information, citizens can not deliberate. Indeed, without being “professionalized”, the citizenry becomes a hindrance to decision making. Everything for the people.

Social movements

Kicked out by institutions, empowered by digital technologies and spurred by the crises (increasingly less cyclical and increasingly more structural, given the speed of change in the new Information Society) citizens organize themselves. Oblivious to the institutions. Even despite institutions.

They organize, and it is worth emphasizing it, the do it in a horizontal way, away from the verticalities of the party hierarchies. And they do it horizontally for two main reasons:

- Because this is the architecture that the new technology — the great enabler of new organizations — promotes above all. One person, one node. While there actually are leaders, they are leaders to the extent that they contribute to the cause, not to the extent of them thriving within and up the organization. And they are leaders while they are facilitators, not fosterers: facilitating the work of the entire network, not just staging their own personal and individual projects.

- Because the new binders are the projects, not big enterprises. While it is true that, by aggregation, projects can generate programs and programs can generate these strategies, in the new movements what is important is trees, not the forest, fishes, not the bank. The initial goal is to save my home, not to change the housing law, while larger institutions begin to change the law and, if given the circumstances, save a handful of homes. And that’s what it means “bottom-up”: not only where the action starts, but the fact that the overall process is reversed.

The problem, as can well be seen in the example above, is that the translation from horizontal to vertical is very complicated. And the shift from project to strategy, from local to global, from what is personal to what is public does require a certain verticality.

It is at this point where I personally agree with those defending tooth and nail the existence of institutions. And it is certainly a crucial point that separates me/us from those who opt for the elimination of the institutions or their reduction to a minimum — and this includes assembly-based movements and anarchists, but also, and it should not be forgotten, extreme liberalism (extremes always meet).

But that we need institutions does not mean that (a) they necessarily have to be the ones we already have, or that (b) even if we keep the ones we have, their design should be the same one they now have. Or, put another way, there is much room for debate between maintaining the status quo — the democratic institutions should be the same ones we already have — and demolishing any semblance of institutionality — direct and/or assembly-based democracy.

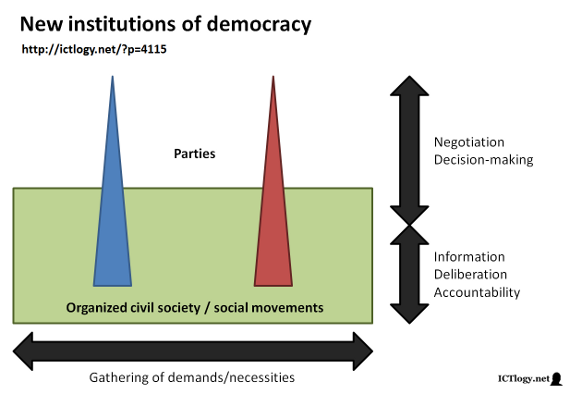

In a world of shadows of grey, away from black or white, there surely is room for a possible hybridization of organized citizens and traditional institutions. This reflection began by saying that the idea was not new, but the context was. It is possible that the great institutions of the past must now split into different institutions, some older ones (parties, unions) who will come to live with some newer ones (or not so new, but refurbished in their inner organization: platforms, movements). I believe that many of the functions taking place inside the classical institutions may end up taking place outside of them and within new institutions. Efficiently and effectively conveyed by technology, without barriers of time and space, it seems possible and even desirable to me to return the information back to the base, to the new institutions of the civil society that will extend the length and breadth of the citizenry and citizenship. Moreover, if there is a place where deliberation — an informed deliberation — can happen, where better than out under the daylight, among peers, with total openness and transparency. Ditto for accountability.

For the rest, to link the global with the local, the collective and the personal, to “verticalize” the demands into decision-making, traditional institutions surely will continue to have an important role… although with severe transformations: like learning how to listen, how to network. They will arguably be much more flexible, probably smaller; relegating power, shifting representation and many other tasks towards the new social movements and civil society organizations. They will have to work together and, therefore, establish ways to collaborate, to mutually enrich themselves, to share the work.

In short, the grassroots levels of the parties should probably be “outsourced” and keep parties not as think tanks or policy-making industries (which largely have by now ceased to be) but facilitators and implementers of proposals. About leadership, the civil society will sooner or later take over.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: david_fernandez, higinia_roig, postdem, ricard_vilaregut

3 Comments »

David Fernàndez. Parliaments. The CUP: one foot on the street, one foot in the Parliament.

We are living the complete exhaustion of the current regime, including a deep defeat of the ideologies of the left.

One of the main factors of this exhaustion and defeat is the privatization of politics: the statement that politics have nothing to do with the citizenry. This paved the path of the total privatization not only of politics but of everything that was the common interest, ending up in the privatization of the welfare state.

Should we recover the institutions as we knew them? Should social movements enter these institutions?

Indeed, there already are many institutions working within the system but with different mindsets such as Coop57, SomEnergia. Xarxa d’Economia Solidària or La Directa.

The CUP benefits from all the social movements that are initiated just after the death of the Dictator Franco and the recovery of the Democracy in Spain. Of course, all the anti-globalization movements of the late XXth century and beginnings of the XXIst century. Deeply rooted in municipalism, the CUP begins to create local assemblies to concur to the municipal elections all over Catalonia, being part of the Parliament out of the question.

But the changes in the way of doing politics and the change in the sensibility of Catalonia regarding nationalism and independentism, the CUP decide to concur to the national elections and win three seats in the Parliament.

The three main courses of action are popular activation, civil disobedience and building of alternatives.

It is a crucial strategy to recover the commons and the common good for the citizenry. In material or infrastructural terms — recovering the assets and the strategic resources of a territory/community — but also in terms of superstructure — recovering the governance of the several institutions that have exert power over the citizenry or can influence public decision-making.

Power is not a space, but a relationship. Thus, if one aims at changing power, one has to change a relationship of power, a relationship usually between two parts: a third party and oneself. Changing relationships of power, thus, begins with changing one’s own practices.

Ways the whole thing can change: feudalist capitalism , democratic fascism or any other form of subtle authoritarianisms, or an egalitarian solution.

Discussion

Arnau Monterde: how is made compatible being in the Parliament and being an assembly-based party on the outside? David Fernàndez: “It’s complicated”. The way it is done is creating 15 work groups within the organization which translate their diagnosis and decisions to the MPs so that they can use the information and decisions in the Parliament. There are also geographic groupings that help to vertebrate the territory.

Ismael Peña-López: technically speaking, the commons is a privatization of the public goods. Is privatization the way to (re)build the common sphere? David Fernàndez: we should separate the goals from the ownership of the commons. If the commons are headed towards providing a public good, this is what is most important, more important than technical ownership. There is no much difference between common and public. In this scenario, private/common ownership is only a second best when one cannot dispute the design of the State and how power is distributed.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: ada_colau, pah, postdem

3 Comments »

Ada Colau. Citizenry. The PAH: from the ILP to the ‘escraches’

We are living the end of a regime, kidnapped by corrupt political en economic leaders. And the regime needs a renovation. How?

How do we rethink social organizations? There is no regeneration of democracy without a strong and well organized civil society. The solution, if any, is not expected from the institutions that corrupted democracy from within. Only a watching and alert civil society will enforce the correct government, as power naturally tends towards corruption.

This social organization, besides its role to watch the power, needs also new forms. Because most organizations nowadays have not aged very well. This includes political parties but also labour unions and NGOs: organizations that were very useful when they were created but that have become useless to provide answers for today’s problems.

The problem is that we [Spaniards] have not been educated into Democracy. We have always been told not to participate in politics. We need to be critical against corrupt institutions, but also self-critical with ourselves and our not-being involved with politics.

And empowerment is the word, the way to do politics (again), to win back for the citizenry the agoras, the squares, the collective discourse, etc.

Back in 2008, before the government and the population in general realized the problem of the housing speculation in Spain, the Plataforma d’Afectats de la Hipoteca (PAH, Platform for people affected by their mortgage) was created to weave a network of people with a common interest. The worst error then was staying in “maximalism”: remaning on the theoretical approach, on the macro approach, on raising awareness on the issue of evictions and personal debt… but not going into action, addressing specific issues, very concrete problems.

The new initiatives of the PAH then attacked several issues in the short, medium and long run, with plural strategies that would address both the macro and the micro levels, the economic crisis and the individual drama of a given citizen, etc.

The Platform succeeded in mobilizing people that had no experience in being mobilized and that did not even had the will to do it: instead of angry people aiming to fight for their rights, the Platform found devastated people being stigmatized by the society. The Platform provided a new mindset, a new context, and a new strategy to overcome the problem: instead of lamenting oneself, fighting for one’s legitimate rights.

Another success was empowering people: it is you that will solve your problems, not anyone else, not the Platform. But the PAH will empower you so that you are able to solve your own problems: no one will defend your case better than yourself. But by oneself does not mean alone, but, on the contrary, collectively and, above all, in a shared way.

All this activity has been done with almost no resources. The person that becomes empowered is reborn and helps others to go through the same process. High level politics can be done with almost no money

.

A last resource for activism is civil disobedience. If a law is unjust, it is not only fair but a duty to fight the law back by disobeying it.

Besides civil disobedience, and in parallel, the mainstream way was also taken, by means of a popular legislative initiative. Of course no practical success came out of it, but two major successes came out of it: raising huge awareness on the topic and de-legitimizing the ones in the Parliament that were proven to be useless to citizen problems even if those were channelled within the system itself.

The main challenge is how to substitute the old mechanisms and institutions with new ones. There is a need for some form of organization: participative, non-hierarchical, democratic… but a form of organization in any case.

Discussion

Q: changes, but towards which way? what scenario can be envisioned? Ada Colau: the horizon is not clear and, above all, we should not rush it. What is clear is that we have to open processes of debate and processes to design this new scenarios. And do not delegate these processes but, instead, be ourselves the main actors. Some urgent initiatives or issues to be addressed is fighting corruption, sanitizing institutions by changing their design (by changing the regulatory framework that shape them), etc.

Q: how do we design the communication strategy? what kind? Ada Colau: this is very difficult because mainstream media react depending on many factors. On the other hand, media tend to identify the movement with one spokesman or visible head. Thus, even if the movement plans a decentralized strategy based on a collective message, while the identification with a specific spokesman works for the movement, ok with it.

Arnau Monterde: how does the movement replicate? Ada Colau: empowerment is without any doubt the most important part of it. Notwithstanding, replication has been an issue from the very beginning: the movement should be able to be replicated, de-localized, decentralized, so that it became sustainable and could grow. Information, procedures, etc. have always been shared and socialized. The movement has taught not only the end users or the members, but also the professionals have been retaught in new ways of sharing their expertise and provide advice openly.

Ismael Peña-López: what is the legitimacy of a Platform such as the PAH to speak with other institutions? Ada Colau: first of all, elections have been proved not to legitimate parties, especially when they do not carry out their own political programmes. On the other hand, anyone can represent the defence of human rights: what the PAH does is to remember that human rights cannot be violated, and asking for respect for the human rights is a duty for everyone.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)