By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 24 April 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Meetings, Nonprofits, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: e-stas, e-stas2008

No Comments »

e-STAS is a Symposium about the Technologies for the Social Action, with an international and multi-stakeholder nature, where all the agents implicated in the development and implementation of the ICT (NGO’s, Local authorities, Universities, Companies and Media) are appointed in an aim to promote, foster and adapt the use of the ICT for the social action.

Here come my notes for session III. (notes at random, grouped by speaker, but not necessarily in chronological order)

Left to right: Raoul Weiler, Jérôme Combaz, María del Mar Negreiro, Berta Maure Rubio

Left to right: Raoul Weiler, Jérôme Combaz, María del Mar Negreiro, Berta Maure Rubio

It will be possible for everyone to access the Internet trough/thanks to low cost devices.

But education will make the difference, not devices.

Jérôme Combaz, Charte pour l’Inclusion Numérique et Sociale

Technology has to be transparent and should address social problems in a social way.

María del Mar Negreiro, European Union Lisbon Strategy

i2010 focuses on uses, digital literacy and how the Internet can help people connect each other, access better jobs, etc. To do so, focus on skills.

Teachers are using — the ones that do — the Internet to prepare their classes, get some materials, but they are not using ICTs when teaching or into the classroom. There still is a reluctance to do so, even if students seem pleased and more motivated when such a thing happens. Lack of skills, lack of time, lack of technical support are among the main reasons adduced by teachers to justify not being more pro-active fostering the use of ICTs when teaching.

Accessibility and usability as a goal to achieve more and better access to the Internet. And, thus, that people find Internet useful for their daily life.

e-Stas 2008, Symposium on Technologies for Social Action (2008)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 24 April 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, ICT4D, Meetings, Nonprofits, Online Volunteering, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: e-stas, e-stas2008, Raul Zambrano, UNDP

1 Comment »

e-STAS is a Symposium about the Technologies for the Social Action, with an international and multi-stakeholder nature, where all the agents implicated in the development and implementation of the ICT (NGO’s, Local authorities, Universities, Companies and Media) are appointed in an aim to promote, foster and adapt the use of the ICT for the social action.

Here come my notes for session I.

Raul Zambrano, UNDP

ICTs, Digital Divide and Social Inclusion

Four stages of ICT Development

- connectivity, get people connected

- content and have people have capacities to deal with it

- services

- participation, Web 2.0

Digital divide

- Within countries

- Among countries

- Within and among countries

The difference between the digital divide in developed countries and developing ones is that in developing ones is but another manifestation of other divides — this is not necessarily this way in developed countries.

How can technology bride social divides, not technological divides?

Divides: differences attributed to knowledge, and differences dues to more physical and human capital.

Both the speed of adoption and the speed of diffusion of technologies are have very different paths in developed and developing countries [So, it’s not just that leapfrogging can be made possible (adoption), but it has to be actually fostered (diffusion). But, part of fostering diffusion to achieve quicker and broader adoption is about giving the population what they need and/or are asking for].

Thus, in the policy cycle (social gaps, awareness raising, citizen participation, agenda setting, policy design, development focused, implementation, evaluation/assessment, reduction of social gaps, new emerging issues), these population needs must be taken into account when designing public policies.

In this policy cycle, networking is crucial to gather all sensibilities and ensure that participation does take place. If there is not citizen participation, public policies are likely to be government’s or lobbies’ interests biased.

All in all, it’s about empowerment.

Comments, questions

I ask whether it’s better push (public led) or pull (private sector led) strategies.

Raul Zambrano answers in the framework of developing countries. In these developing countries, the Estate is to foster and create aggregated demand, it is the main purchaser, investor and installer of ICTs (infrastructures, services, etc.).

On the other hand, it is true that there is a latent demand from the citizenry, and there already is a manifested need for ICTs.

About the private sector, the problem in developing countries is that the private sector might not have resources enough to set up pull strategies. Or maybe they could, but it still makes poor sense for them when looking at the Return of Investment. This is especially true with developed countries firms trying to get established in developing countries, though local enterprises might not think (and behave) alike, and find it’s huge benefits what elsewhere might not even make it worth it trying.

So, put short, in developing countries what seems to be working is a centralized model but progressively decentralized [as the subsidiarity principle in the European Union, I’d dare add].

Do we need to keep on working on access (if everyone already has a cellular)?

Yes, definitely, but not as an independent variable but as a dependent one [this is one of the cleverest statements I’ve heard in months about the digital divide].

Paco Ortiz (AHCIET) intervenes in this issue: incumbent telecomms normally pay a ratio of their profits to governments so the latter can help solve the last mile issue. The problem being that once these governments have cash to do so, the sometimes shift the funds to other priorities — no critique intended: these priorities can be Education or Health. Thus, legitimate or not, the result is that universal access is never achieved, but not at the private sector’s fault.

One person from the audience harshly attacks governments for their corruption, which invalidates them to foster any kind of policy or to get any kind of funding from whom ever.

Raul Zambrano states that it is precisely transparency and accountability one of the main goals of ICTs in the sphere of the government.

e-Stas 2008, Symposium on Technologies for Social Action (2008)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 27 March 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: actor_network_theory, ethnography, research, telecenter, telecentre

No Comments »

Daniela de Carvalho Matielo presents a PhD seminar at the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, UOC.

Challenging the digital divide: the role of telecenters in e-inclusion practices.

First, Daniela brings a short introduction to the concept of the Digital Divide as lack of access to ICTs.

Digital Inclusion is then the effort to guarantee everyone has access to the Information Society.

The problem is that there is not only one digital divide, but many: geographical, etc.

These efforts have, hence, many designs, from fiscal incentives to direct provision of Internet access from physical places: telecenters, places people can go to use telecommunication services. The main difference with a cyber cafe is profit — in the latter case — or bridging the digital divide — in the fomer case —.

Three moments of digital inclusion (according to Warschauer):

- Device model: physical access

- Connexion model: access to the Network

- Literacy model: uses and contexts

A shift is now taking place towards a more social-aspects focused strategy:

- What are the main competences to use the computer: digital literacy

- What are the uses that certain communities can give to computers and the Internet: technology appropriation

But it seems that this shift has gone from “technological determinism” to “social determinism”, from an approach where technology would solve each and every problem (cyberoptimism) where just everything can be solved inside the “black box” of the community.

But, technologies are not neutral and the actor-network theory (ANT) can bring some light to the issue.

What do we have so far?

- Official reports about telecenter use and users

- Scientific studies, both qualitative and quantitative

“Community Informatics” is a field whose goal is to analyze the uses of ICTs in communities.

Research Questions / Hypotheses

- Technology plays an important role. This role is usually neglected at higher levels.

- There is a big differnetce between practice and goals in telecenters as stated in their official discourses

Following the ANT, there’s an interaction — chains of association — between users and technologies so, after passing through a “black box”, become from digital illiterate to literate, and from technologies to properly appropriated technologies.

The methodology to be used in this research will be, based on the ANT, do an ethnography in a telecenter to disclose the relationships of technology appropriation by users.

Comments

- Several persons in the audience state that ANT might not be the best approach, as it takes for granted that there is a role performed by technologies, and a relationship technology-user, which is exactly what the research wants to find.

- I state that this could be balanced (theory vs. practice, positivism vs. normativism) by balancing ANT with a participatory action research instead of performing an ethnography.

- Somebody also points that it would be interesting to see how digital literacy (strictly personal) can be complemented with technology socialization, so a social framework is created through technology, so the digital literate can then interact “technologically” with others, and socialize.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 March 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, e-Readiness, ICT4D

3 Comments »

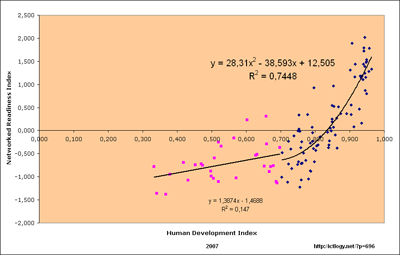

Two years ago we here spoke about e-Readiness and the Human Development Index. The chart we then plotted was similar to this one:

This chart now adds two tendency curves: one (exponential) for countries with a Human Development Index (HDI) over 7.00, and another one (linear, though absolutely irrelevant, on the other hand) for countries under 7.00 — though there are lots of countries missing: too poor to appear on the charts…).

Even if the regression is not really accurate (not at all) we can more or less see a relationship between e-Readiness and Development (as measured as HDI).

One of the main criticisms I have against how the digital divide, the Information Society or e-Readiness is measured (see below “More info” for a couple of references) is that it either takes one of the following paths:

- Focus almost exclusive on infrastructures

- A too broad approach thus including “analogue noise” (i.e. non-digital indicators or analogue economy indicators — provided such a thing makes sense, which I believe it does in the field of development)

In any case, huge voids appear: digital literacy levels, the regulation framework and richness of content and e-services.

Are these lacks relevant?

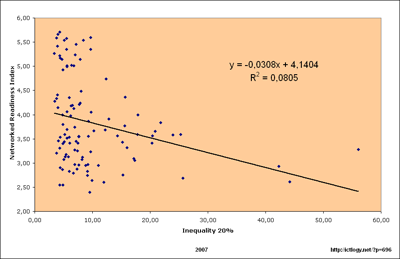

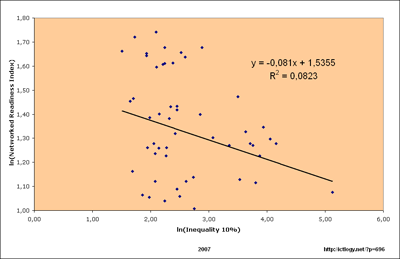

Let’s take a look at the measurement of Inequality (from the HDI database, calculated after the World Bank’s World Development Indicators), comparing the ratio of 20% richest ones to 20% poorest ones, and ratio of 10% richest ones to 10% poorest ones. And we chart it against the year 2007 World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index (we plot the second one logarithmically, just for a change):

As can be easily seen in both comparisons — linear for the 20% to 20% inequality; logarithmically for the 10% to 10% inequality — there does not seem to be any kind of relationship between e-Readiness and Inequality. But whose problem is this? the reality’s or our models’? Does it really make sense that a country with highest inequalities can be as e-ready as another one with a more balanced income/wealth distribution?

It is no news that income inequalities carry on associated inequalities in education, in political stability, social and community engagement, security and crime, etc. So, can a society with low/uneven human capital, political instability, poor community engagement, high crime rates… be as e-ready as another one with better scores in these indicators? Intuition clearly and loudly shouts no, not at all, by any means.

Then, where’s the problem? In my opinion, it undoubtedly is in how we measure how good our degree of Information Society development is.

And, if so, where are we failing? I guess here are some places to look at:

- We pay too much attention to infrastructures. They are needed, of course, but they are means, not ends. ICT infrastructures should be seen as a necessary condition for ICT development, but not as a sufficient condition.

- We quite always forget about digital literacy, getting rid of it with a simple “number of Internet/PC/mobile phone users” indicator, an indicator which does not measure how different uses can leverage ICTs for development.

- Even if we approach digital literacy, aggregate measures do not discriminate between different users and the individual benefits they get, or how their different levels of skills impact on their productivity or their employability.

- At the aggregate level, it is easy that big firms’ ICT achievements and Governments’ big investments overshadow poor ICT adoption and performance by SMEs, thus provoking a paradox: at the aggregate level, ICT investment and consumption is great, but “no one” is using them (a reframing of Solow paradox?).

- Our knowledge on how ICTs affect social parameters — out of the Economy arena — is way too poor. So, we are having tough times to incorporate such parameters in our e-Readiness models and indices. Does e-Administration, e-Government and e-Democracy matter? At what level? Does ICT skills matter in multi-factor productivity? At what level? Can this be included in our models?

Put short: I guess we are missing people in our models. I am not saying it is easy to do, but we are actually missing the key.

More info

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 03 March 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, e-Readiness, ICT4D

3 Comments »

In a recent event where I was invited to debate about the need whether to foster the Information Society, I was shocked about some positions from both some of the speakers on the round table I participated in and the audience.

The starting point was: is there a need to foster the Information Society, or the Web 2.0 is a sufficient empowerer so there’s no reason to set up centralized strategies and policies?

One of the first arguments to come to debate can be summed up by “if people find no interest on the Internet, they will not use it, even if the infrastructures are ready and affordability is good enough”.Which I absolutely share: people like Lenhart (2000), Compaine (2001) or Parks Associates (2007) have already given evidence about this fact — this is, of course, especially relevant in developed countries, but it is also true in the poorest parts of them, so extrapolation to developing ones could be possible.

The next argument comes straightforward: we cannot force anyone to enter the Information Age. Again, I agree.

Disagreement comes with the next statement, primarily defended by the political representatives in the room: neither should we force anyone to enter the Information Age nor should we try to convince them to. Otherwise, we would be patronizing them, being paternalistic and acting like enlightened elites, and so on. We have to stop being cyberoptimists: people know better than anyone what their needs are, if people just want to share their photos, the only thing we [the government] have to do is to offer [subsidized] Flickr courses for anyone

.

The argument is: don’t trust the doctor, because he’s being an enlightened elite prescribing antibiotics for your infection (not trying to save your life); don’t trust anyone that tells you to fix your roof, because he’s being paternalistic and patronizing (not just giving advice against it collapsing with the next rain).

The evidence of the economic impact of ICTs is great and growing. And there is plenty of people out there doing research about the issue. Elites? Not at all: people (scholars, politicians and experts in general) whose job (they are paid for it) is to give advice i.e. on the consequences on the job market of being digitally literate… or illiterate. You can disagree on interpretations, but not on data.

Honestly, I think that, these days, the difference between cyberoptimists and cyberskeptics is tiny:

- Cyberoptimists will tell you that there’s plenty of evidence of the coming of age of the Information Society and that the potential possibilities are many

- Cyberskeptics will tell you that there’s no evidence of huge benefits of entering the Information Society, but will agree that there are huge losses of not doing it (i.e. you might not increase your productivity being digitally literate, but you’ll surely loose it if you’re not)

The rest of the story is about swindlers and cyberblind. Yours to choose.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 08 February 2008

Main categories: Digital Divide, Hardware, ICT4D

Other tags: developing countries, laptop, mobile phones, olpc

4 Comments »

I’ve been recently interviewed by e-mail by journalist Ignacio Fossati. He put clever questions that made me think, which I really appreciated. Some of my answers were grounded on plain evidence, but other were just my own opinion — arguably all of them. As most of the interview dealt with “cheap technologies for Developing Countries”, such as the OLPC project, and we’ve been having some debate lately here, with Teemu Leinonen or at Peter Ryan‘s, I thought I’d share them here, so the debate can go on.

In bold characters, the questions; the answers following.

Cheap laptops, what do you think their acceptance will be like in developing countries? Do you think it will be a success?

Personally I think that they will undoubtedly have some acceptance. In part because there already is a government demand, but in my opinion, they will above all get into these countries through the private sector. The great success of Negroponte and his OLPC project has not been to create a new device, but breaking the spiral “more powerful hardware – new software demanding more hardware power – more powerful hardware – new software demanding more hardware power – etc.”, and showing that it is possible a good hard with a limited soft and vice versa.

Once broken this dynamic of “more, more, more,” the private sector will enter with force into a market of billions of potential users so far neglected because they could not afford that “more hardware, more software.”

I also believe that the mixed model pda+phone (smartphone) can be an interesting trojan horse, given the high penetration of mobile and the already numerous management applications for cellulars in those countries and that have been very successful.

Do you think the production of low cost laptops is the best way to extend and promote the use of computers in the Third World?

Absolutely not. But with two shades/comments.

The first one is that it has already been demonstrated — in developing countries, but in developed countries as well — that the user (citizen, Administration, firms) should see some use (and benefit) in the computer or the Internet. If not, once large infrastructures have been installed (e.g. wire) these will clearly be unused or underused. The laptop, without some clear uses in its design, has neither present nor future.

However, and this is my second nuance, this computer, accompanied by an intelligent design in the field of uses (e.g. a teaching method based on distance education, educational content embedded by default on the computer, a learning plan of shared learning within the family, etc.) can be a spearhead that will break the natural rejection that most of us adopt in front of a new technology.

Therefore, it is by no means the solution, but may be part — and, in fact, be the most attractive sometimes — of a comprehensive plan to promote the Information Society based on content and services.

These proposed low-cost products for developing countries (laptops, mobile phones, cars …), can actually help to reduce the gap of the digital divide?

This question has a short answer and a long one.

Of course, all that implies mainstreaming Information and Communication Technologies helps to narrow the digital divide, by definition: more technology, less gap. Elemental.

The long answer has three parts.

The first, and we discussed: the technology is useless if not used. All in all, and like any technology, the computer is just a tool, for communication and information in a digital world. If, in the end, we cannot access neither information nor communication, the gap remains.

Which brings us to the second part: quality. It is now already (almost) more worrying the quality of Internet connection that the penetration itself: many services require increasingly broadband to operate optimally. Therefore, if these low-cost products have, in addition, low performance, their contribution to bridging the digital divide is also tiny. We should not be thus confusing cost with performance.

Last, the digital divide is a reflection, a derivative of the socio-economic gap. In this regard, if these devices do not reduce poverty or increase welfare, sooner or later, the digital divide will widen as currently are social inequalities. We would then be putting a patch or attacking the symptoms rather than the disease.

Is there room for a number of competitors in the market for low-cost computers?

At the state we are in, we have to count connected computers. According to the statistics, 17% of the population in the World is already connected. So there still is a 83% left to be covered. Moreover, if we include both homes and businesses, we can potentially achieve (as happens with telephony in many countries) more than 100% penetration. So, effectively, and in theory, there should be room for everyone.

Of course, the problem is not supply, but demand: who among these 5.5 billion people can afford to be connected? That is the question to be solved. Mobile telephony, low-cost computers, wi-fi and mesh networks have provided a good bunch of examples of people who previously could not afford connectivity and that now can. And other examples have shown that, if there is a way to make the cost worthwhile (by reducing other costs due to use of technology), this is usually not a barrier.

Do you think that behind this “solidarity rush” hides an unreported trade war?

Businesses, by definition, with their owners and stockholders behind, are not nonprofits. And that’s it. They look for profits: this is their role and we should not make value judgments on this issue.

What is reprehensible is when these firms try to convince us of otherwise, or, much worse, when they harm others with their economic activity.

Almost 90% of the money that goes into research and development is spent on the development of technologies to serve 10% of the richest people in the world. Could this trend be changed or is there something being done in this matter?

I fear that the capitalist system works this way. We need to generate surplus value to satisfy the owner of the capital, and this can only be achieved by selling to the one that can pay, which is the richest.

It occurs to me, however, two ways to reverse this trend:

The first one, the more usual one, is trying to socially share the profit beyond benefiting a few stockholders. It is the model of most agencies for international cooperation, development aid and private foundations and NGOs in general.

The second one is the opposite: try to have more people that can buy things so that 10% becomes a 20%, 30%, etc. That is, betting for the development of the poorest to enable them to be good consumers, so that they “count” on the global scene.

Simplified example: we may investigate malaria (which does not affect the majority of developed people) and provide free vaccines as a way of sharing the wealth (in kind in this case), or we can increase the purchasing power of people who suffer from malaria so they can make demand for vaccines grow and hence the market believes that it is a profitable market to do research in this disease.

Both options have been supported and criticized simultaneously, by people working in development cooperation and solidarity: on the one hand, considering the most disadvantaged as a mere consumers (and squeeze them for profit) is something inhuman; on the other hand, is a way to make development more sustainable in the long run, abandoning charity (which would be the first option presented before) for further development in the strict sense.

But this is another debate ;)