The European Commission is in the process of reflecting the past, present and future of telecentres or, in general, public Internet access points (PIAP) or, even in a broader sense, e-Inclusion Intermediaries (eI2).

Amongst others, there are four important issues that are guiding this reflection:

- What has the impact been so far.

- How has the techno-social scenario changed since they were initially born: increasing adoption of ICTs, importance of broadband, mobile Internet, etc.

- How has the socio-economic scenario also changed, i.e. the economic and debt crisis in Europe.

- According to the preceding points, what should be done in the future and how, that is, how public policies to foster the Information Society should be designed in matters of universal access/usage.

In this framework, the Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS) organized an Expert Workshop on Measuring the Impact of eInclusion Intermediaries in Europe: towards an impact assessment practice?, that took place in May 3-4 in Seville, Spain, and to which I was invited to participate and to contribute with a position paper.

My position paper should verse on the future of telecentres in Europe in 2020, and it was supposed to be what I call a “grounded opinion”: grounded, because it is based on both personal/professional experience and lots of readings; opinion, because, all in all, I was asked to provide my own point of view, what would I do was I to design the policy that would deal with e-Inclusion Intermediaries.

Position paper: eInclusion Intermediaries in Europe: horizon 2020

State of the development of the Information Society

I believe that the development of the Information Society has come not to a dead end, but near a point of stagnation:

- The industry and governments are most of the time still thinking in terms of infrastructures: how much, how are they managed, what is the regulation to bind them and what is they state of usage (usually in percent of saturation).

- Users only care about a huge supply of content and services (for whatever the use) and that these run on affordable infrastructures.

This is, of course, a simplification. But a peek at what governments are measuring and what media are broadcasting gives us an idea of the tremendous bias towards the preceding aspects of the Information Society.

The problem with this scenario is that it has no future, as policies centred in infrastructures are targeting an almost non-existent problem:

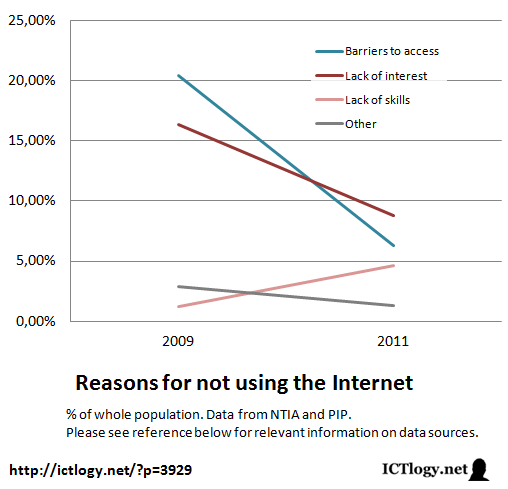

- In general terms, physical access is becoming a minor issue (remember: Europe 2020). It already is, especially if we do not take into account as an indicator “households with Internet access”, but “people covered by access to Internet”.

- The former point is due, in part, because many last mile issues have been solved (e.g. with mobile Internet, e.g. with public Internet access points such as telecentres, libraries, cybercafes, schools and many other venues).

- The supply of content and services is buoyant.

The missing gap: capacity building

On the other hand, the two growing problems remain unaddressed by public policies:

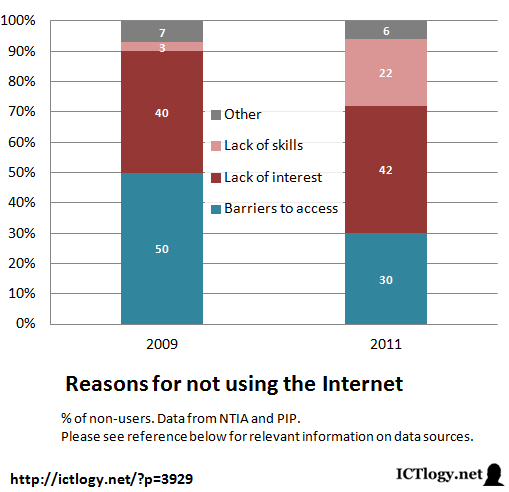

- A stable share of ‘refuseniks’, that choose not to use the Internet for several reasons.

- A growing share of citizens that do need digital skills and literacies that they lack or have to acquire when and if possible.

These two gaps have two main consequences:

- An ICT sector which a shortage of supply in terms of highly qualified workers and human capital in general.

- A quality of usage of the Internet characterized by inefficacy and inefficiency, and that many find will be (already is) the core of a second digital divide, deeper that the digital divide of access and more difficult to fix because of its (human) nature.

State of the question, the missing gap and e-Inclusion Intermediaries

How do e-Inclusion Intermediaries face the state of the question and the missing gap? In my own (grounded) opinion, either they change or they will perform badly.

- Telecentres (understood as not-for-profit and for-development-aimed) will suffer from economic resources shortage, because of the economic crisis and because of Internet penetration. Cybercafes (understood as for-profit and comercially-aimed) will suffer from social sustainability shortage, because of the economic crisis (what solutions are you providing?) and also because of Internet penetration.

- Most e-Inclusion Intermediaries have traditionally provided or recently began to provide services related to e-skills. The problem is that those skills are becoming much more complex than simple techonological skills and, indeed, it is a set of digital literacies and capacities that is required. Are eI2 responding to that?

- In the same train of though of literacies, what we have found in our conversion from an Industrial Society to an Information Society is that we have done quite good in learning or appropriating technologies an to applying/adapting them to our usual processes. But we have definitely failed in improving most processes and socioeconomic transformation is but a good bunch of “good practices” that we all know but cannot replicate.

A forecast/proposal for e-Inclusion Intermediaries

- The telecentre should become an eCentre, a centre that is not a physical place, but a reference resource that can actually be located in a specific location, or embeded within an organization. Telecentres should be insourced in other institutions: in a firm, in a civic centre, in a library, in a government, in an NGO…

- Complementary to the former statement, many of the telecentre functions can and should be outsourced. There is evidence that the probability of survival of a telecentre is linked to it being part of a telecentre network: share knowledge, share resources, share contents and services. Outsourcing can take the shape of a core+franchises or a flat network. But reinventing the wheel should be forbidden.

- If we believe in the insourcing/outsourcing pair, partnerships come naturally: e-Inclusion Intermediaries should complement a shared project with their added value, while other partners should be left to do the same. Partnerships with governments in the field of sheer “for development” inclusion or fostering e-government; partnerships with the private sector to leverage the expertise in the field and sell it for the sake of economic sustainability; look out for firms to be included as targets of eI2.

- Of course, purity should be abandoned: no more either telecentre or cybercafe. It’s about e-Centres and it is about to provide knowledge. The function is what matters and not the means: the function is part of the mission, the means are part of the business/operating plan.

- But the function is not fostering ICTs, the function is Inclusion. The ICT centre has to become a Centre-on-ICT-steroids. It is the community — the target — what matters, it is about supporting neighbourhoods, schools, entrepreneurs, living labs… not about supporting ICTs. But we do it with ICTs because we believe in its huge potential.

Some bibliography

Based on my own experience

Bibliography on the impact of telecentres

First Monday, September 2006, 11 (9). [online]: First Monday.

First Monday, 2 November 2009, 14 (11). [online]: First Monday.

Information Technologies and International Development, 4 (4), 31–45. Cambridge: MIT Press.

The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 46 (1), 1-14. Kowloon Tong: EJISDC.

Performance Measurement and Metrics, 10 (1), 33-48. Bradford: Emerald.

Information Technology & People, 23 (3), 247-264. Bradford: Emerald.

The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 49 (2), 1-11. Kowloon Tong: EJISDC.

The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 52 (1). Kowloon Tong: EJISDC.

The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 45 (3), 1-23. Kowloon Tong: EJISDC.

Information Research, 14 (4). Sheffield: Tom D. Wilson.

The Journal of Community Informatics, 7 (1&2). Vancouver: Journal of Community Informatics.

Asian Journal of Communication, 18 (4), 365-378. London: Routledge.

Information Technology in Developing Countries, February 2012, 22 (1). Ahmedabad: Centre for Electronic Governance.