Most of the definitions about the networked educator — or the networked teacher — are clearly biased towards tools: if you one uses a specific set of tools for education, then one is a networked teacher. This is, in my opinion, a very narrow approach to what has been called the “teacher 2.0” or, in more general terms, “education 2.0”. In El Profesor 2.0: docencia e investigación desde la Red (Teachers 2.0: teaching and researching from the Net, 2006), my colleagues César Córcoles, Carlos Casado and I stated that a teacher is, above all, a researcher, and that some digital tools constituted a new framework for collaboration among researchers

and that this new frameworks allowed to increase their communication and motivation capacity in the classroom, and to optimise the efforts devoted to searching for information, collaborative work and the communication of their results

.

That is: it is not tools, but usage, what constitutes the basic foundations of a an academic panorama with greater collaboration between peers and a natural evolution of the current meritocracy system

. It is not using blogs, or microblogs, or social bookmarks, or online video, or whatever the tool, but how and what for one will use them. And, most especially how will that affect one’s own tasks, organization and decision-making.

Distributed leadership

Eric S. Raymond and Yohai Benkler, among others, remind us that one of the deepest impacts of the digital revolution is the increase in the granularity of tasks, that is, how big tasks can be split in smaller tasks in ways that were not either possible, effective or efficient in prior times. This increase of granularity usually leads to more actors doing things and in separate ways, almost immediately leading to people making decisions on their own, in a decentralized or even distributed way.

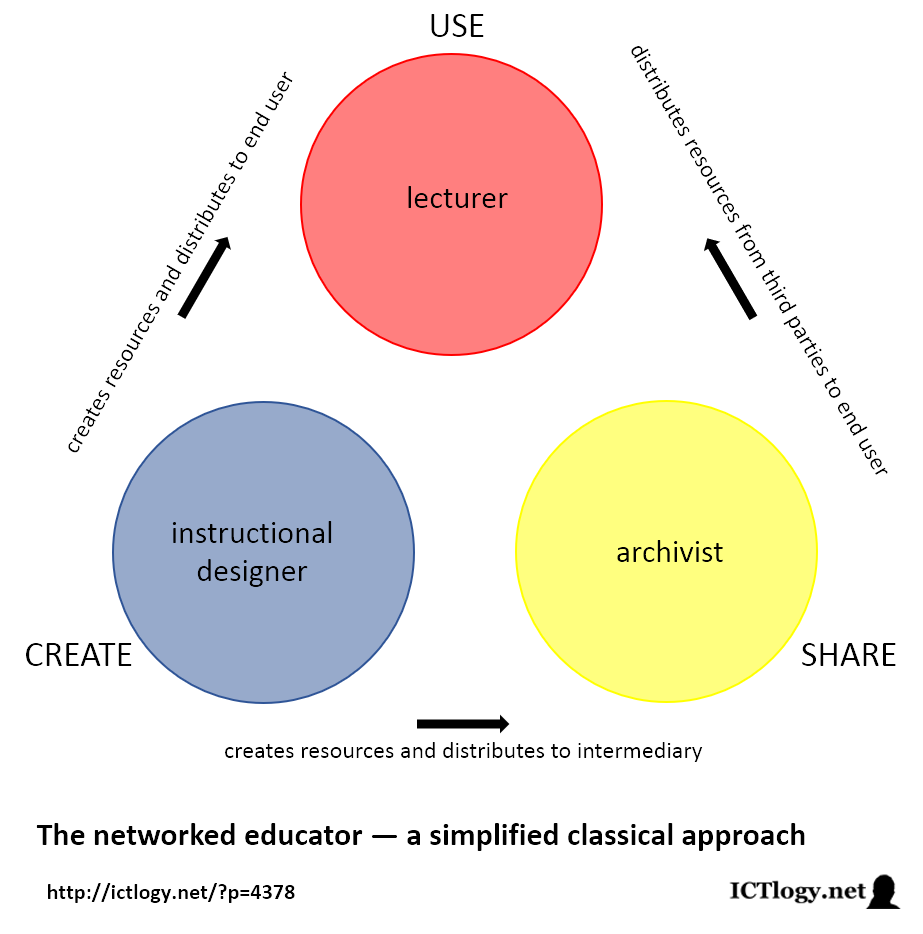

A first approach to this distributed leadership can be illustrated with an example. In a world without Internet, a teacher will usually prepare their own material and teach with it. With Internet, is much more possible that someone will prepare a given material (create), make it available to others (share) and a third party will bring it to their lecture (use). Of course, this already happened with the internet (publishers made textbooks, librarians piled them up, lecturers used them), but the scale at which this can happen with the Internet is potentially different by several orders of magnitude.

And not only the scale — in quantitative terms — but the qualitative terms can be dramatically changed too: while a publisher can prepare some educational resource and distribute it top-down to a group of lecturers, a real community of practice can prepare that very same resource, each one of the members contributing with their fraction of knowledge, and use the result while retaining the freedom to chose, adapt, edit, improve, etc. before, during or after the use.

A hierarchic, individualistic, world of educators

Let us simplify how educators work in a traditional world. The simplification has no implicit judgement, but aims at trying to make things more understandable.

Usually, a teacher lectures. To do so, she can either use a textbook from an instructional designer — that sells her work to a publisher that sells the book to the teacher or the school —, or use other resources from a library or any other archive (which is usually fed by the very first instructional designer. Of course, there are many variations and shades of grey to this scheme but, in general terms, it looks very much like this:

The networked educator — an approach from distributed leadership

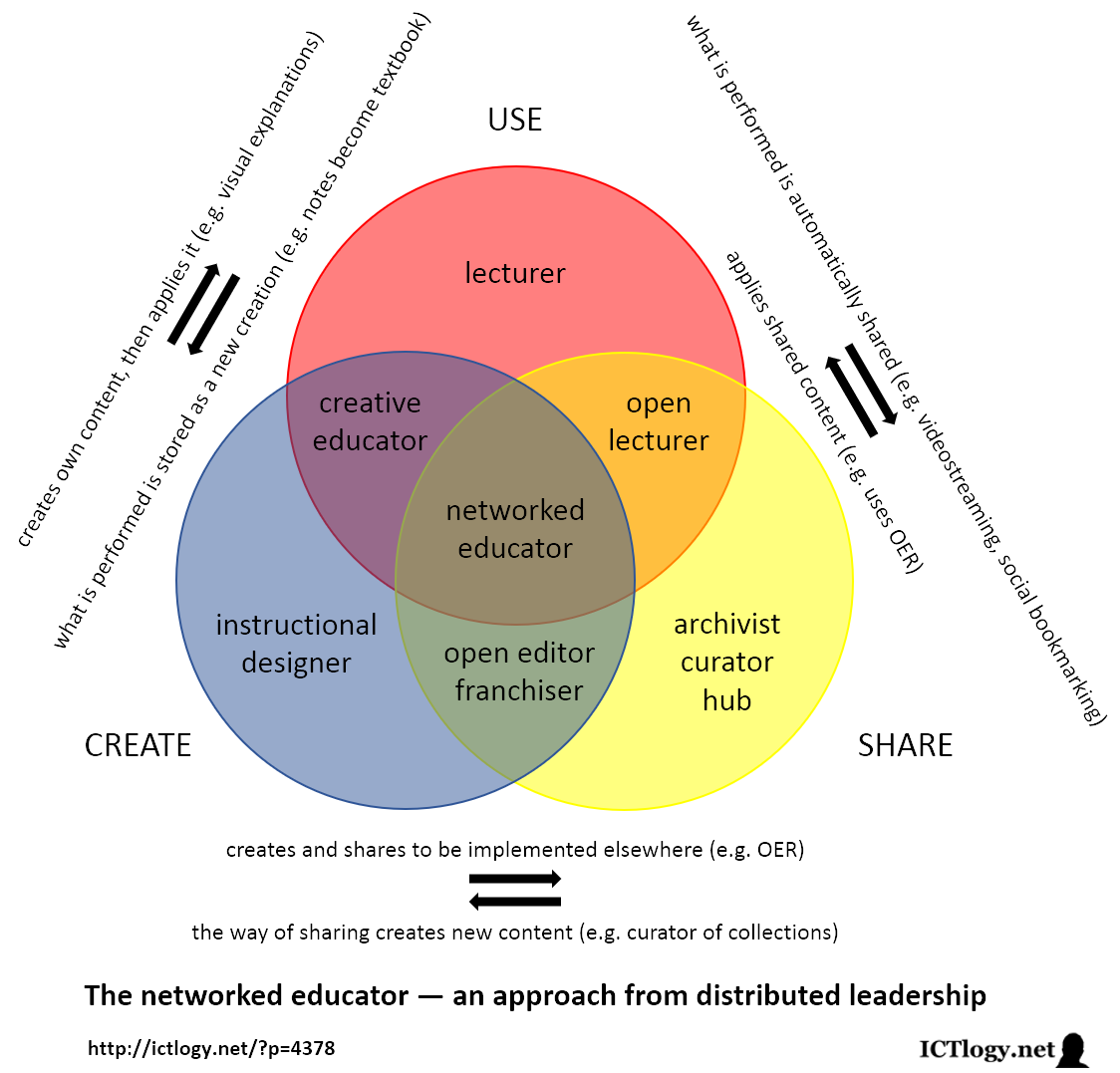

Let us now go up the ladder of complexity:

- The solipsistic model: an individual teacher does it all. Mostly, lectures live, like in the oral tradition.

- A hierarchy does it all, distributes directly or indirectly (through archivists such as libraries) supporting resources to the teacher, which applies them to her lectures.

- All tasks of the creation, sharing and using processes are split among different actors, most of them shifting roles every now and then.

The last step can be drawn like this:

Instead of a linear, directed way of doing things, of making decisions, here tasks overlap and actors change roles constantly, thus generating different hybrid roles. Besides the three traditional/simple ones — instructional designer, archivist, lecturer — others add to the set:

- The creative educator is the one that can create educational resources, and then put them into use in her own lectures; but it can also be a teacher that is able to store what she is doing in the classroom: notes that become a textbook, a taped lecture that becomes courseware.

- The open lecturer makes publicly available the results of her lectures… or of the classrooms work (e.g. open wikis where collaborative work happens); but also is able to find existing resources that can be applied in to her classroom.

- The open editor creates content that is made publicly available. If made on purpose, so that a certain model can be replicated, I call it franchiser.

But the most important actor is the one that lies on the middle of the scheme, the one that is able to do — and actually does — it all.

- The networked educator (I prefer it to networked teacher, because one can educate without teaching) easily shifts from creation to sharing, and from sharing to implementation, and so on. And, indeed, she usually even transforms the individual tasks that were formerly well established. Thus, sharing can no more be something about making available through archiving, but also being a curator of content, or a hub through which one can find more and better content.

This is, of course, a very very simplistic approach to this issue. But it is helping myself to identify the tasks that make up education (and learning) and how can technology subvert the dynamics of the educational process, which is, to me, the most interesting impact of the digital revolution in learning and most especially in the educational system.