By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 14 June 2012

Main categories: Development, News, Nonprofits, Online Volunteering, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: francesc_balague

5 Comments »

Some months ago, professor in Social Pedagogy Xavier Úcar approached Francesc Balagué and I and told us he was very worried: after many years working in the field of community action, the Internet had come and changed every definition we had on what a community was, and changed every definition we had on what interaction (or action) was too. He had just found out that community action might be lagging behind the pace of times. And he invited us to write a book on the new communities and how did they interact on the net, so that he and his colleagues could use it to catch up with new scenario after the digital revolution.

An appealing invitation as it was, we had grounded reasons not to accept it: one of us is a pedagogue specialised in instructional technology and the other one an economist specialised in the impact of ICTs and development. Thus, we knew almost nothing about community action, and only had a chaotic approach to new expressions of communities working together in the most different types of ways and goals. That is precisely the point

, stated professor Úcar.

Hence the heterodoxy of the inner structure of the book that has just seen the light. Acción comunitaria en la red (Community action in the net) is neither a book on community action nor a book with very clear ideas. It is, but, a book that invites the reader to think, to elaborate their own conclusions, and to find out which and whether these conclusions can be applied and how to their own personal or professional cases.

The full book has been written by 15 authors and presents 8 case studies that depict and analyse how a specific community used the Internet and its different tools and platforms to share information, communicate amongst them, organize themselves and coordinate actions in order to achieve their particular goals. The structure of the chapters analysing the cases was totally free, but some relevant questions had to be answered somehow:

- What were the history, motivations, goals of the community?

- What led the community to use the Internet? How was the community articulated digitally? what provided the Internet that could not be found offline?

- How was the process of adoption of digital technologies, what tools and why?

- What happened to the sense of membership, identity, participation?

- What was the role of the mediator, facilitator, leader and how does it compare with an offline leadership?

- Is self-regulation possible? How was conflict handled?

- How is digital knowledge, experiences and learning “brought back” to the offline daily life and put into practice?

The cases are preceded by two introductory chapters, a first one on the social web and virtual participation, and a second on digital skills, as we thought some common background would help the reader to better understand some digital practices (and jargon). The book closes with what we, both authors, learnt during the preparation of the book and from reading other people’s chapters. This concluding chapter can be used too as a guideline for the preceding cases.

Table of contents

From the official page of the book Acción comunitaria en la red at Editorial Graó.

- Introduction, Francesc Balagué, Ismael Peña-López.

- What is the Web 2.0? New forms of participation and interaction. Francesc Balagué.

- Brief introduction to digital skills. Ismael Peña-López.

- APTIC. A social networking site for relativos of boys and girls with chronic diseases and conditions. Manuel Armayones, Beni Gómez Zúñiga, Eulàlia Hernández, Noemí Guillamón.

- School building: new communities. Berta Baquer, Beatriu Busquets.

- Social networking sites in education. Gregorio Toribio.

- Networked creation and the Wikipedia community. Enric Senabre Hidalgo.

- Social networking sites in the Administration: the Compartim programme on collaborative work. Jesús Martínez Marín

- Local politics, organizations and community. Ricard Espelt

- Towards cyberactivism from social movements. Núria Alonso, Jordi Bonet.

- Mobile phones, virtual communities and cybercafes: technologicla uses of international immigrants. Isidro Maya Jariego

- Concluding remarks. Ismael Peña-López, Francesc Balagué

Acknowledgements

There is a lot of people to be thankful to for making the book possible.

The first one is Xavier Úcar. I have only seldom been granted such a degree of total confidence and trust, not only in my work but in myself as a professional. He was supportive and provided guidance to two ignorants in the field. He totally gave us a blank cheque and one of my deepest fears during the whole process was — and still is — to have been able to pay him back with a quality book. I really hope it has been so.

The authors of the case studies were just great. Some of us did not know each other and I can count up to three people which I still have to meet personally (i.e. offline). They also trusted in us and gave away a valuable knowledge and work that money won’t pay. Many of them won’t even make much use of adding a line on their CVs for having written a book chapter. I guess this is part of this sense of new communities that the whole book is talking about.

My gratitude (but also apologies) to Antoni Garcia Porta and Sara Cardona at Editorial Graó. I am fully aware that we made them suffer: we succeeded in transferring some of our chaotic lives to them when they had not asked to. Being an editor today must be both a thrilling and a difficult challenge. We all gave away time in the making of the book but the published they represent invested money too, and that is something that we quickly forget these days.

Last, but absolutely not least, it has been a real pleasure working with Francesc. I think we only met once during the whole process: when Xavier invited us to coordinate the book. Francesc then packed and went around the world for 14 months. Luckily he took his laptop and would connect every now and then. Our e-mail archive and Google Documents can testify that almost everything is possible if there is the will to do it.

And it was fun too. Oh, yes it was!

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 30 March 2011

Main categories: Development, ICT4D, Online Volunteering

Other tags: agcre, nptech

1 Comment »

I was invited to present a keynote during the VII General Assembly of the Spanish Red Cross, on 26 March 2011. I was asked to talk about what should nonprofits do in view of the proliferation of social networking sites, online participation, cyber-activism and so.

In such cases, I generally try to avoid the usual showcase of “best practices” and go instead to what causes made possible those “best practices”. It’s a tougher option, as it often implies a trade-off from the “wow factor” towards the “what-is-this-guy-talking-about factor”. On the positive side, I pursue the trade-off from the “let’s-copy-these-actions” towards “I-know-why-they-worked-and-I-understand-how-to-design-them-myself”.

On the other hand, the representatives of the Spanish Red Cross were choosing their President and the members of the boards of directors of different regional levels. That was a very strong reason to shift towards more strategic issues instead of strictly practical and punctual applications of social media and nonprofit technology.

Thus, the structure of my presentation was explaining:

- What caused the transition from an Industrial Society to an Information Society;

- how people were leveraging their access to information and communication technologies for activism and self-organization;

- what was being the impact like for institutions, especially those that represented people’s interests: governments, political parties and non-governmental organizations.

In a nutshell, the main message was that the Internet, cellphones, social networking sites, etc. are not a matter of how you inform your stakeholders, how you communicate with your volunteers or how you convince your donors, but a dire change of the game-board that requires serious strategic reflections and decisions in the very short term. Evidence shows that many institutions will either go through a deep process of transformation or will simply disappear, and NGOs are included in the set.

More information and downloads

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 11 December 2010

Main categories: Development, e-Readiness, ICT4D, Meetings

Other tags: ictd2010

No Comments »

I am presenting two posters at the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (ICTD2010).

The posters are, actually, the usual poster and the corresponding academic paper explaining what the poster is picturing. Below can be found the two papers and the two posters for anyone to download. The posters are a set of 8 slides in A3 size plus a first slide that maps how to build the puzzle so it all ends up with the actual A0-size poster.

Information and Communication Technologies and Development (2010)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 12 May 2009

Main categories: Development, Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Meetings

Other tags: apc, chat_garcia_ramilo, gem, gender, gender_evaluation_methodology

1 Comment »

Live notes at the research seminar Gender Evaluation for Social Change by Chat Garcia Ramilo, Coordinator of the Association for Progressive Communications Women’s Networking Support Programme, Manila (Philippines). Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Castelldefels (Barcelona), Spain, May 12th, 2009.

Gender Evaluation for Social Change

Chat Garcia Ramilo

Why gender evaluation? Evidence showed that ICT4D did not integrate gender considerations, though evidence also shows that effectiveness and impact of development projects increases if gender is integrated in design, planning and evaluation.

Based on participatory action research.

- Testing and development of a gender evaluation tool for ICT4D projects: teleworking, ICT training projects, telecenters, etc.

- Capacity building in gender evaluation: telecenters, rural ICT projects, ICT policy processes and localization (of content)

Findings and challenges

- a gap in capacity for analysis and evaluation of gender-based inequalities

- weak focus on gender in project design, implementatoin and policy formulation

- how to develop evaluative thinking about gender and ICT4D, and use it to shape new gender practices within the ICT4D sector? how to make it in a participatory action research framework?

How gender makes a difference in ICT4D and access to the Information Society:

- Comparative access to infrastructures by women and men are determined by income levels

- Capacity affected by literacy and education levels

- Services affected by relevance of service, mobility, safety issues

- Governance affected by opportunities for participation in policy processes

These aspects have to be taken into consideration if one is to design an ICT4D project in a specific place. The design of this project will sensibly be different depending on how gender is affecting the former issues.

But gender is not only about “women issues”, but also about social and cultural variables, how do the interplay of these variables impact on women and men.

The Pallitathya model

The Pallitathya help line Blangladesh center is a help desk service which consists in five basic components:

- local content

- multiple channels of information and knowledge sharing

- intermediation or infomediation, human interface between information and knowledge-base

- ownership

- mobilisation and marketing

This project’s desing helped women with specific queries (related to gender) or with lower literacy rates to reach a knowledge that, had the ICt4D project been designed in a different way, they would most probably have missed.

Philippine Community e-Centers

Telecenters in peri-urban areas. Though in absolute terms there were not much difference in usage rates amongst women and men, difference could be seen in how the telecenters were used and what values they assigned to them. For instance, women used the telecenters as ways to meet people, as ways to socialize. There were also differences in patterns of access and utilization in relation to age, education and income.

Fantsuam’s Zittnet Service — Nigeria’s first Community Wireless Network

To increase female uptake of the Internet, especially in rural areas.

Coverage of signal was not the issue, but hardware and high costs of bandwidth. Still, even if coverage was good, women had to travel to the centers, and this was a barrier for uptake, as also was low literacy levels.

Maybe it’s not about a wireless network, but embedding this project into a wider one aimed to reduce poverty by supporting rural female farmers. Besides, there is a clear preference towards voice communication over written, and SMS over the Internet.

SOS SMS

In distressful situations, women can send an SMS that is received by 5 institutions. Besides reporting of harassment and direct action by the authorities, these messages can be aggregated and thus infer patterns and profiles where harassment and distress are more likely to happen.

Why ICT4D (for women)?

- ICTs can provide access to resources and contribution to income, knowledge, etc.

- Indirect impact of ICT4D and access to income, knowledge, education, etc. on self-confidence and self-esteem. ICT4Ds have an impact on empowerment, in changing relationships, in agency.

- Emergence of new roles (of women).

- Changes in relationships

Why gender evaluation in ICT4D?

- Evidence of change in gender roles and relations can be used for more gender sensitive policies and programmes.

- Evaluations contribute to developing benchmarks and indicators for gender equality in ICT

- Developing capacity in gender evaluation (and gender planning) is a key contributing factor in mainstreaming gender in ICT for development

Q & A

Q: What’s the general procedure for such projects? A: There are mentors that capacitate evaluation facilitators through workshops, and then an evaluation plan is developed together with all the members of the partnership working on the project. Online spaces are created (e.g. with Ning) to support interaction and network creation.

Assumpció Guasch: It’s easier to work about gender evaluation if the promoters — especially governments — of ICT4D projects already have some gender awareness. Another issue is knowing the ICT Sector and the Industry, what’s the legal framework they’re facing. And it is also important knowing what are the technological issues that are crucial in these projects.

Q: How important is the role of capacity building? How is sustainability dealt with in gender projects? A: To be able to have some impact, capacity has to be built. As part of the capacity building strategy, handbooks and toolkits are built so that a certain levels of capacity and impact can be achieved quickly. Empowerment is, arguably, a measure of sustainability, as the more empowered the people the more self-replicable the model. But projects are not that easy to translate from one place to another.

Cecilia Castaño: Besides direct, action and empowerment, a gender focus has also some other derivatives: a sense of listening to “unheard” people, creating community and raising awareness about gender.

Comment: mobiles vs. Internet? People like Barry Wellman state that mobile phones help strengthening the strong ties (e.g. family), while the Internet helps broadening your network of weak ties.

Ismael Peña-López: can the Gender Evaluation Methodology be transposed to other collectives (e.g. immigrants, lower income collectives, etc.) so that to better design ICT4D projects? I guess that in gender-based projects there is a part that is strictly related to gender, but another part that deals with identifying and managing inequality and difference. Inasmuch there is a “managing the difference” issue, I wonder whether some gender-based projects could be just slightly adapted to identify and improve other projects aimed to bride other “differences”: educational, income, etc. Methodology, handbooks and toolkits, etc. could be then split in two parts: identifying, managing and evaluating the differential factor; and then focusing in the specific differential factor: gender, education, age, income, disabilities…

A: Gender is not only man vs. men but is much more complex: education, income, etc. So, it really makes sense to address the gender issue in itself. A gender approach does not mean that the project is focused towards the e-development of women, but just trying to include a new variable in the project. And there’s gender everywhere, so it maybe does not make a lot of sense thinking about “taking gender out” of the equation.

Assumpció Guasch: some projects in Extremadura (Spain) have tried to apply gender methodologies into e.g. age issues. The difference between gender and other issues is the pervasiveness of the former.

More information

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 26 April 2009

Main categories: Connectivity, Development, e-Readiness, Hardware, ICT4D

Other tags: m4d

No Comments »

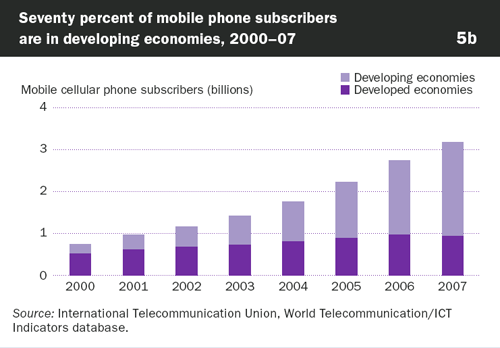

The World Bank’s last edition of the World Development Indicators stated that Seventy percent of mobile phone subscribers are in developing economies

, a mantra that was also repeated on Saturday April 25th, 2009, at Africa Gathering. At least during the second talk it was said that 61% of the 2.7 billion mobile phones in the world are in developing countries

, as reported by Ken Banks. Besides whether it is 61% or 70%, the thing is that 83.3% of the World population live in developing countries, a fact that puts in perspective the relative (i.e. per capita) penetration of mobile phones in relationship with the rest of the World’s.

So, is there no reason to be optimistic about mobiles in Africa, then? Well, it depends. Let’s bring some data in for the rescue:

| Mobile cellular subscribers |

000s (2002) |

000s (2007) |

Compound annual growth rate |

Cellphones per habitant (%) |

% digital |

% of total phones (mobile + fixed) |

| Africa |

36923.8

|

274088.0

|

49.3

|

28.4

|

91.0

|

89.6

|

| Americas |

255451.3

|

656927.1

|

20.8

|

72.2

|

30.9

|

69.8

|

| Asia |

443937.4

|

1497499.0

|

27.5

|

37.7

|

69.1

|

70.6

|

| Europe |

405447.7

|

895057.4

|

17.2

|

110.9

|

84.1

|

72.9

|

| Oceania |

15458.9

|

27011.5

|

11.8

|

79.4

|

97.6

|

69.2

|

| WTI |

1157219.1

|

3350583.0

|

23.7

|

50.1

|

67.6

|

72.2

|

Source: ITU ICT Eye

Or, graphically:

Data don’t clearly show the distinction between developing and developed countries, though it can be roughly inferred at least by (sorry for the rude simplification) looking at Africa and Asia (with mostly Low and Lower-middle income economies with very few exceptions — see the World Bank’s Country Classification). The big highlights are:

- Developing countries have less cellphones per capita than developed ones

- Most phones in developing countries are mobile and digital

- The compound annual growth rate of mobile telephony is higher the less saturated is the market

A logical comment about the last statement would be that it’s natural that less penetration leads to higher annual growth rates. Well, it is not that logical: on the one hand, there are countries with penetration rates above 150% (United Arab Emirates, Macao, Italy, Qatar or Hong Kong), so the concept of “saturation” is a tricky one; on the other hand, there are plenty of other commodities and capital goods (e.g. cars or washing machines) that not even dream of reaching these growth rates.

That said, one need to be cautious when stating that there are “many” cellphones in developing countries: this is true in absolute terms, but most untrue in relative ones. But reality shouts out loud that this is changing at an overwhelming speed and that innovation happens at a terrific pace.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 23 April 2009

Main categories: Development, Digital Divide, ICT4D

Other tags: wdi, world_bank

1 Comment »

(continued from World Development Indicators 2009: a commentary (part I))

The services are still unaffordable for many people in low-income economies, leaving them yet to realize the potential of ICT for economic and social development

This is quite evident by most data available, so my comment will be headed not on the fact of the digital divide, but on affordability itself.

According to my own research (again, more to come soon), after analysing 55 models that depict digital development and include more than 1,500 indicators, if we let aside the analogue indicators (e.g. GNP), 37% of the digital indicators were depicting the state of infrastructures, of which only one sixth were measuring affordability.

The rationale behind this argument is that not only most people cannot afford ICTs, but, according to what we measure, we can infer that most measuring tools — which are normally built to measure the impact of policies and strategies and projects — simply do not care or care little about affordability. If people cannot afford ICTs and policy-makers and decision-takers (amongst them development institutions) do not care about affordability, we’ve got a problem. A big one.

In developing economies innovative use of ICT services is changing people’s lives and providing new opportunities

Not that I disagree with this statement — have I already cited the Economic Benefits of ICTs? — but there is a shade of meaning to be made here. I increasingly think that ICTs are not a driver of inclusion but a driver of exclusion. In other words, people have to move (or develop digitally) to remain in the same place. ICTs actually do not create new opportunities, but the absence of ICTs or digital illiteracy do decrease the number of opportunities available to those on the wrong side of the digital divide.

See, for instance, the next figure that I presented — among other places — in my speech Digital students, analogue institutions, teachers in extinction and that is based on Manuel Castells’ Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society and Informationalism, Networks, And The Network Society: A Theoretical Blueprint:

Mobile phones have captured the market in developing economies […] Seventy percent of mobile phone subscribers are in developing economies

The first part of this statement is absolutely true and people in developing countries — citizens or development agencies working in the terrain — know it perfectly. See, for instance, Mobile Web for Development or Innovative Uses of Mobile ICTs for Development.

But the second part is definitely misleading, as the next chart is:

Stating that 70% of the total mobile phone subscribers are in developing economies says little about the relative weight of such penetration. According to the World Bank itself, there are 6 billion people alive today: One billion people live in developed countries [while] the other 5 billion live in developing countries

. Which is to say: 83.3% people live in developing countries. Compared with 70% of total cellphone subscribers, there still is a gap of 13.3% in favour of developed countries. And if we take into account international agencies, development organizations and tourists (…and troops) — that buy domestic SIM cards to have local prices — the unbalance is even worst.

I am not saying that news are bad — which are not —, but that they are not as good as they might seem at first sight.

More information

, 20MB).

, 20MB). Source:

Source: