By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 17 June 2014

Main categories: Education & e-Learning, Meetings

Other tags: enterforum, victoria_camps

No Comments »

Victòria Camps

How to educate in an audiovisual environment?

When looking at cyberspace, we have to avoid being apocalyptic or integrated (à la Umberto Eco). It is “just” a different way to get information, to communicate, to buy, to engage people (in politics), etc. So, we cannot moralize over a world that is deeply and quickly changing from the point of view of an ancient regime that is fading away. We have to try and be objective. And the question is: is the Network a progress? Always?

The Internet has made some physical characteristics (race, gender…) irrelevant for discourse, has desacralized the centres of wisdom and creation of knowledge, has decentralized (or shifted) the centres of knowledge. On the other hand, knowledge is increasingly vulnerable in the Information Society: being informed is not the same thing as knowing something.

The Internet has proven to be a revolution for political engagement, as it contributes in building community.

One of the most important rights in this new Internet-led age is the freedom of expression.

But every right of freedom has to have its limits, and the limits of freedom of expression are privacy and honour.

And what happens with the respect to one’s own privacy? That is, what happens when people do things on the Internet that they would never do offline. Are we losing intimacy? Is there a right to be forgotten?

Democracy can be deeply changed thanks to the Internet, but we need lots of good information so that we can decide on solid ground. But who certifies what is quality information? We need new professionals — or traditional professionals focussing on specific tasks — that filter and certify good information: journalists, teachers…

What happens with intellectual property? It is property as in the offline world.

On the Internet, we need self-regulation and self-regulation means education: formal education, education within the family.

Enter Forum (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 06 April 2014

Main categories: Digital Divide, Digital Literacy, ICT4D, Writings

Other tags: diarieducacio, e-intermediaries, libraries, telecentres

No Comments »

Idescat — the Catalan national statistics institute — published in late 2013, the update to the 2012 Library Statistics where it stated, among other things, that in 2012, “the number of users grew up to 4.5 million [the Catalan population is calculated to be 7.5 million], 18.3% more than two years ago”. Almost a month later, Professor Xavier Sala-i-Martin stated at the national television that “when the Internet comes, librarians lose their jobs”. This statement was later on developed with more depth in his blog post Internet, Librarians and Librarianship.

Can both statements be true at the same time? Or is someone plain wrong?

Probably the best explanation for these apparently opposing statements, and one explanation that makes them fully compatible, has to do with the present and the future of libraries.

In recent years we have been witnessing how Information and Communication Technologies turned everything upside down, especially (but not only) knowledge-intensive activities. And, among all knowledge-intensive institutions, libraries are no doubt part of the leading group. The Public Library Association explains the whole matter: an increase in the demand for library services, an increase in the use of WiFi networks, in increase in the use of library computers, an increase in training on digital skills. In short, most users are not only going to libraries asking for borrowing books — which they of course do — but they increasingly go to libraries looking for a means to gain access to the Information Society.

But not merely physical access but quality access: what in the arena of digital inclusion has ended up being called the second digital divide. That is, once physical access to infrastructures has “ceased” to be an issue, what is needed is training in digital skills, and guidance in its use. Using an extemporaneous metaphor, once one has a new car, what she then needs is a driving licence.

So, we see there is more demand. But what about staff cuts?

It turns out that, unlike many of the traditional roles of libraries, when it comes to overcoming the first (access) and second (skills) digital divide, many different actors come together to work in the later issue. Both inside and outside libraries. These new actors simply are a consequence to the change (or enlargement) of the roles of the library, a consequence that has now found competitors both in the market as in the public sector itself. A recent study by the European Commission, Measuring the Impact of eInclusion actors shows how, in addition to libraries, many other actors work in the field of e-inclusion (each one in their own way), such as telecentres, Internet cafes, some schools, fee WiFi access points, some bookstores, bars and cafes, etc.

These new actors, indeed, also often operate inside libraries: libraries many times subcontract the services of telecentres or other “cybercentres” — or their personnel’s — either for managing the public computer network or to impart training related to digital skills.

So, summing up, this is what we have so far: the growing need for digital competence does increase the use and demand for training in issues related to information management (and therefore fills libraries with people) but the diversity of functions and (new) actors means that, in the end, it take less ‘librarians’ but more ‘experts in information management and digital skills’.

Yes, some concepts are written between quotation because, most likely, they already are or will soon be the same thing. And thus we enter the topic of the future of libraries.

Empirical evidence tells us that information, the Internet, is increasingly ceasing to be a goal in itself, a differentiating factor, to become a generally purpose technology. If getting to the information ceases to be a goal to become a tool it is because it a (usually ad hoc) tool to be used “passing” in the pursuit of another task. Whatever that is: today it is practically impossible not to find a job, whatever trivial may be, that does not incorporate a greater or lesser degree of information, or of communication among peers.

Thus, beyond getting information it now becomes mandatory learning to learn and managing knowledge: it is not, again, about gaining access to information, but about taking control of the process of gaining access to information, of knowing how one got to a specific set of information so that the process can be replicated it in the future.

Finally, and related to the previous two points, access to information ceases to be the end of the way to become a starting point. Thus, the library and other e-intermediaries become open gates towards e-Government, e-Health, e-Learning… almost everything to which one can add an “e-” in front of it.

That is, information as an instrument, the quest for information as a skill, and getting to the desired piece of information to keep looking for information and be able to perform other tasks also rich in information. And begin the beguine.

Tacitly or explicitly, libraries are already moving in this direction. If we forget for a moment politeness and political correctness, we can say that libraries and the system working in the same field are already leaving behind piling up paper to focus on transferring skills so that others can pile their own information, which most likely will also not be printed. Fewer libraries, but more users.

It’s worth making a last statement about this “system working in the same field” because the formal future of libraries, especially public ones, will largely depend on (a) hot they are able to integrate the functions of the “competition” or (b) how they are able to stablish shared strategies with this competition.

If we briefly listed before telecentres, cybercafés, schools, free WiFi access points, bookshops, bars and cafes as converging actors in the field of e-intermediation, we should definitely add to this list innovation hubs, co-working spaces, fab labs, community centres and a large series of centres, places and organizations that have incorporated ICTs in their day to day and are open to the public.

This whole system — libraries included — is not only working for access but for the appropriation of technology and information management; they have make centres evolve into central meeting places where access to information is yet another tool; and they have become areas of co-creation where the expected outcome is a result of enriched information resulting from peer interaction.

The future of the library will be real if it is able to cope with these new tasks and establish a strategic dialogue with other actors. It will probably require a new institution — not necessarily with a new name — that allows talking inside the library, or cooking, or printing 3D objects or setting up a network of Raspberry Pi microcomputers connected to an array of Arduinos. Or mayble the library — especially if it is public — should lead a network of organizations with a shared strategy so that no one is excluded from this new system of e-intermediation, of access (real, quantitative) to knowledge management.

I personally I think that libraries are already at this stage. I am not so sure, though, that is is the stage where we find the ones promoting a zillion e-inclusion initiatives, the ones promoting modernizing the administration, educational technology, smart cities and a long list of projects, all of which have, in essence, the same diagnosis… but that seemingly everyone aims at healing on their own.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 10 January 2014

Main categories: Education & e-Learning, Meetings

Other tags: 9forumice, enric_roca, ice, igop, innovation, marius_martinez, quim_brugue

No Comments »

Round table: Innovation in times of change of era

Chairs: Enric Roca, professor of the Department of Systematic and Social Pedagogy, UAB.

What values and what frameworks promote innovation? Which ones are a barrier to it? What characterizes innovative schools and innovative projects?

Joaquim Brugué, director of the Institute of Government and Public Policies (IGOP), UAB.

As these are times of change, it seems common sense that institutions should change too. Thus, innovation look like the best means to drive this change. But change makes change more complex. Problems become wicked, problems that cannot be simplified or reduced to simpler components. There is no simple answer or, simply, not just one single answer.

BUT: instead of trying to approach wicked problems in different and many ways, what institutions are doing is to specialize put all their effort in being more efficient and effective in their field of specialization… leaving wicked problems unsolved or, at least, providing wicked problems with one single perfect solution that actually does not solve all the complexity of the given issue.

This is the approach of a technocratic society or a technocratic organization that creates no externalities, no networks, no lateral vision.

Màrius Martínez, professor of the Departament of Applied Pedagogy, UAB.

We heavily rely on our own mindsets and mental frameworks, which drag us and stop us from looking at problems from different points of view.

Only dialogue can make these mindsets emerge, ideas be exchanged, and mindsets be changed, or adapted to others’.

There is a need to have a culture of transformation, of “why not?”, to give a chance to change, to transformation.

Once there is such a culture, innovation becomes explicit — not tacit — and can be transferred, replicated.

We have to have a systemic point of view, to look at the whole so that we can clearly frame the problems, the resources, the possibilities.

Trust and accountability, not suspicion and control.

Leadership has to be strong, but distributed, leaving room for collaboration and participation.

Provide resources, especially time, but with some planning, with deadlines, so that accountability can happen.

Emphasis on learning, on development. Innovation has to target learning, learning of the students or of the teaching stuff, but innovation has to lead to learn more and better things. And innovation has to be also an acknowledgement. The acknowledgement that (1) something is wrong and (2) it is wrong that something it is wrong. And, thus, it has to be fixed. Learning and equity are linked to innovation.

Martínez: innovation requires a shared project. And this shared project, or vision, is usually illustrated with a motto. The shared project and motto helps in building a story, a tale, a dialogue.

Discussion

Enric Roca: Does everyone has to be an innovator in their same role? Can we specialize? Should we not?

Quim Brugué: there should not be such a role as “the innovator”. Instead, conditions have to be created where innovation can happen. These conditions include, most of the times, dialogue and the hybridization of approaches.

Màrius Martínez: in an innovative environment, people feel like agents, agents of change. So, yes there is a need to find agents of change. Distributed leadership is about identifying the existing talent and putting it to work. In this train of thought, maybe the term “good practices” is not as good as “practices of reference”.

Quim Brugué: we have to be aware that what we take for learning is not sheer imitation. This is the risk of having “practices of reference” which, in the end, evolve into bad copies.

Màrius Martinez: the currículum should be put in crisis and, in this exercise, the student should have a leading role.

Q: why most institutions and people deny complexity? Màrius Martinez: sometimes it is a matter of perception, that is, of not perceiving complexity. Quim Brugué: sometimes because complexity is a blocking scenario and, thus, decision-makers rather approach not complexity but simplicity, where traditional rules and tools used to work.

IX Fòrum Educació (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 25 August 2013

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: e-democracy, social_movements

No Comments »

The following paragraphs do not intend to present an idea particularly new, although I think it is pertinent to say that they seek to revisit an old idea under a new context.

On the other hand, this is more an intellectual exercise — or even a speculation — rather than an academic proposition. However, it is fair to acknowledge that this exercise does not appear out of the blue. On the contrary, it is firmly based on two recently published works and the respective bibliographies that support them:

- Casual Politics: From slacktivism to emergent movements and pattern recognition (bibliography).

- Spanish Indignados and the evolution of 15M: towards networked para-institutions (bibliography).

Finally, although this discussion has been cooking in the oven for the last few months, I can not leave unsaid that Daniel Innerarity’s latest op-ed — ¿El final de los partidos? [The end of parties?] — has been the final trigger. The article — a highly recommended reading — goes on to state that although the world has changed, the institutions of democracy (governments, parliaments, political parties, unions, nonprofits, etc.) are still the best way we have to organize our lives in society. And that these institutions being reformed, but in essence those are the ones we have and the ones we should be keeping.

Institutions and democracy

Les us simplify as much as possible — with the consequent risk to fall into inaccuracies, generalizations and biases — what is a liberal democracy.

Since policy is no longer the management of the polis, citizenship has been alienated from the exercise of directly and personally ruling public affairs. This is no answer to no plan hatched in the dark to uptake power, but mainly responds to reasons of efficiency: the polis has become a county, a region, a state, a global world that requires full-time leaders, professionals that can manage the enormous complexity of politics and that, of course, serve all citizens and respond to them and their needs. No one can afford devoting themselves to managing public affairs and, at the same time, managing personal matters and earning their livelihoods. At least not without the slaves who had our Greek ancestors (some of our contemporary representatives actually have someone working for them, or just neglect public affairs, but this is another matter).

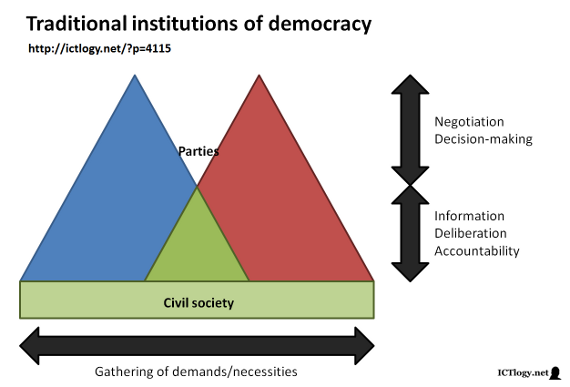

We have created, thus, institutions that represent us politically and work for everyone. At the lowest level of those institutions (e.g. political parties or labour unions) many citizens participate (joining, sympathizing, collaborating) to gather information on the needs and demands of their peer citizens, as well as deliberating on the various possible solutions.

At another level, a few representatives (governments, parliaments) are responsible for making decisions, after having negotiated the wills of the various groups represented. At the end of the cycle, this level ensures accountability of the decisions made before the lower level.

The general population, given the difficulty of being informed and engaged, remains outside the whole process and only follows it remotely through the press, political propaganda and punctual moments of participation through the ballot box.

Crisis of institutions

There are at least four reasons why current political institutions have seen their legitimacy diminishing in the process of representative (or institutional) democracy:

- Because the professionalization of their boards has become not a means but an end in itself. Staying on the job happens to be the goal of many in office, getting out of line of what should be their genuine purpose: to serve the citizens they represent. This deviation or sheer abandonment of the original mission of the institutions, of course, has happened at the expense of the legitimacy and the gradual withdrawal of citizenship.

- This professionalization has crowded out from the foundations of the institutions those citizens who saw participation as a vocation of service and not as a professional vocation. This expulsion may have been active or reactive, but the results have been clear: thinning of the bases and withdrawal (again) of the bulk of the citizenry.

- The increasing complexity of politics, together with the professionalization and the brain drain of the institutions has resulted in the worst of situations: trivialization and playing down of the complex, simplifying the political message and its consequent radicalization of ideas. The political debate becomes meager, addressed to media, puerile, rather than strengthening deliberation and seeking learning in the democratic process. In the absence of political pedagogy, behold disaffection.

- Last but not least, many of the previously mentioned issues may not have a solution, but they could in deed have a strong contribution thanks to the new Information and Communication Technologies (information and communication: how often we forget the meaning of the acronym ICT). There are many things that ICT could help on: encourage participation and engagement of talent, transparency and accountability, dialogue and debate. If they are not a magic solution, their negation itself is a clear statement of principles: although the use of ICTs may have great potential in all areas of politics, we have no intention of putting them into practice and realize this potential. More disaffection, especially from the ones who could and would participate.

Consequences?

On the one hand, the thinning of the bases of the institutions, especially those closest to the citizenry (parties, unions). On the other hand, the shift of information and accountability “upwards”: the same ones that negotiate and make decisions are the same ones that are informed about what is “necessary” or “convenient” being done, and are also the same ones that are accountable amongst themselves.

The result is a growing disconnect with the society due to the shrinking of the social bases and the lack of in-depth, “vertical”, technical and political paths of the implemented policies. Deliberation is not only absent but even avoided. Without information, citizens can not deliberate. Indeed, without being “professionalized”, the citizenry becomes a hindrance to decision making. Everything for the people.

Social movements

Kicked out by institutions, empowered by digital technologies and spurred by the crises (increasingly less cyclical and increasingly more structural, given the speed of change in the new Information Society) citizens organize themselves. Oblivious to the institutions. Even despite institutions.

They organize, and it is worth emphasizing it, the do it in a horizontal way, away from the verticalities of the party hierarchies. And they do it horizontally for two main reasons:

- Because this is the architecture that the new technology — the great enabler of new organizations — promotes above all. One person, one node. While there actually are leaders, they are leaders to the extent that they contribute to the cause, not to the extent of them thriving within and up the organization. And they are leaders while they are facilitators, not fosterers: facilitating the work of the entire network, not just staging their own personal and individual projects.

- Because the new binders are the projects, not big enterprises. While it is true that, by aggregation, projects can generate programs and programs can generate these strategies, in the new movements what is important is trees, not the forest, fishes, not the bank. The initial goal is to save my home, not to change the housing law, while larger institutions begin to change the law and, if given the circumstances, save a handful of homes. And that’s what it means “bottom-up”: not only where the action starts, but the fact that the overall process is reversed.

The problem, as can well be seen in the example above, is that the translation from horizontal to vertical is very complicated. And the shift from project to strategy, from local to global, from what is personal to what is public does require a certain verticality.

It is at this point where I personally agree with those defending tooth and nail the existence of institutions. And it is certainly a crucial point that separates me/us from those who opt for the elimination of the institutions or their reduction to a minimum — and this includes assembly-based movements and anarchists, but also, and it should not be forgotten, extreme liberalism (extremes always meet).

But that we need institutions does not mean that (a) they necessarily have to be the ones we already have, or that (b) even if we keep the ones we have, their design should be the same one they now have. Or, put another way, there is much room for debate between maintaining the status quo — the democratic institutions should be the same ones we already have — and demolishing any semblance of institutionality — direct and/or assembly-based democracy.

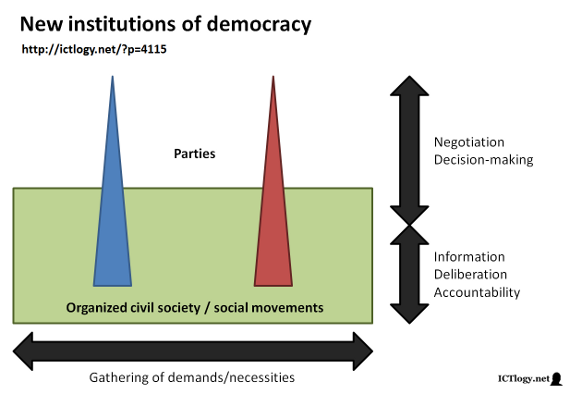

In a world of shadows of grey, away from black or white, there surely is room for a possible hybridization of organized citizens and traditional institutions. This reflection began by saying that the idea was not new, but the context was. It is possible that the great institutions of the past must now split into different institutions, some older ones (parties, unions) who will come to live with some newer ones (or not so new, but refurbished in their inner organization: platforms, movements). I believe that many of the functions taking place inside the classical institutions may end up taking place outside of them and within new institutions. Efficiently and effectively conveyed by technology, without barriers of time and space, it seems possible and even desirable to me to return the information back to the base, to the new institutions of the civil society that will extend the length and breadth of the citizenry and citizenship. Moreover, if there is a place where deliberation — an informed deliberation — can happen, where better than out under the daylight, among peers, with total openness and transparency. Ditto for accountability.

For the rest, to link the global with the local, the collective and the personal, to “verticalize” the demands into decision-making, traditional institutions surely will continue to have an important role… although with severe transformations: like learning how to listen, how to network. They will arguably be much more flexible, probably smaller; relegating power, shifting representation and many other tasks towards the new social movements and civil society organizations. They will have to work together and, therefore, establish ways to collaborate, to mutually enrich themselves, to share the work.

In short, the grassroots levels of the parties should probably be “outsourced” and keep parties not as think tanks or policy-making industries (which largely have by now ceased to be) but facilitators and implementers of proposals. About leadership, the civil society will sooner or later take over.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2013

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: postdem, ricard_espelt, roger_pala

4 Comments »

Roger Palà. Media. Mediacat and the Yearbook of the media silences.

Media are suffering a crisis of legitimacy as important as parties’. Indeed, media are reproducing all the bad practices that other powers are. How can we re-legitimze media? How can we return media to their role as watchdogs and not as part of the power? This crisis of legitimacy has been running for at least 15 years. If they have emerged now is due to two main reasons: (1) the financial and economic crisis that have deepened the crisis of journalism, as they lack more now resources and (2) the emergence of social networking sites.

There has been an important devaluation of contents due to lack of resources but also due to accommodation of the professional. This has ended up with bad practices like do not checking the sources, lack of self-criticism, etc. But changing the system from within (i.e. Association of Journalists) is very difficult, so the Grup Barnils opted for initiating some activities “in the margins”. With Media.cat a project was created to point at bad practices in journalism, creating reports on the state of the question of media, etc. The flagship project is the Yearbook of the media silences.

But the point (of the yearbook and in general) is not a general criticism against media, but raising awareness on the crisis of the sector, the reasons for the crisis and the ways to try to fix it. The approach, in fact, is rather constructive and awards the good practitioners more than condemning the bad practitioners.

The Yearbook has had increasing success and one of the reasons is twofold. On the one hand, because it has raised a lot of awareness on the issue and, on the other hand, because it has relied on the citizens to back the project, through crowdfunding initiatives but not only, as citizens have spread the word about the whole process and not only about the final outcome.

The con side of the initiative is that it is a one-time-a-year thing, not very fairly paid and with difficulties of sustainability.

The good thing is that despite being a very small collective, an impact has been made, especially in the field of media.

Discussion

Q: is it true that social networking sites make it more difficult to hide things? Roger Palà: absolutely. A good thing of social networking sites is that they break the monopoly of the agenda-setting.

Arnau Monterde: what is the future of media? is it possible a network-based model? will we see for long the traditional model of mass-media? linking the economic crisis with the crisis of media, is it legitimate? Roger Palà: it is absolutely true that money enables professionalism and professionalism usually enables quality content. This does not mean that media have to be big: we are witnessing the emergence of small initiatives that, despite being small, they are 100% professional and are looking for new niches and new ways of working. We will surely see a new cosmos of few big media and a constellation of small media living together.

Q: isn’t there room for citizen journalism? Roger Palà: yes, sure, but the problem is sustainability in the long run. Is it possible to sustain quality and engagement and professionalism without a comfortable economic position? Maybe, but stability helps a lot in sustainability.

Institutions of the Post-democracy: globalization, empowerment and governance (2013)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 08 March 2013

Main categories: Information Society

Other tags: dario_quiroga, joan_torrent, thesis_defence

1 Comment »

Notes from the PhD Dissertation defence by Darío Quiroga Parra entitled TIC, conocimiento, innovación y productividad: Un análisis empírico comparado sobre las fuentes de la eficiencia en América Latina, países asiáticos y la OCDE (ICT, knowledge innovation and productivity: an empirical compared analysis on the sources of efficiency in Latin America, the Asian countries and the OECD), directed by Joan Torrent Sellens.

Defence of the thesis: ICT, knowledge innovation and productivity: an empirical compared analysis on the sources of efficiency in Latin America, the Asian countries and the OECD.

What is the evidence of new sources of efficiency? What is the stage of the transition towards a knowledge economy?

The literature has already found an evidence of a direct impact of ICTs on the growth of productivity, and an indirect effect of ICTs on productivity and innovation, due to the complementarity between ICTs, organizational practices, innovation and human capital.

The hipotheses are:

- New sources of co-innovation marginally explain the level of productivity in LatAm.

- The differential of the growth of productivity between LatAm and Asia and the OECD is due to new sources of efficiency.

A revision was made to find what were all the determinants of productivity and innovation, which were the sources of productivity and, most specifically, which ones were the new sources of productivity and which one s the new sources of co-innovation.

Co-innovation factors were built after adding up components by using factorial analysis. That is, it was found what combinations of variables, combined together, better explained innovation.

Two levels of co-innovation were found:

- Weak co-innovation: 2 different factors

- Strong co-innovation: 3 different factors.

Regressions show that co-innovation has appeared since 2000 (regressions made with data from 2000, 2006 and 2008) and is significant, having a positive impact on innovation and productivity. For LatAm, nevertheless, weak co-innovation is more important than for OECD countries, where strong-innovation is the most important one. Coefficients clearly grow from 2000 to 2006, while they tend to stabilization in 2009.

On the other hand, Asian countries boost productivity by adding more capital to their production functions, and not by co-innovation. On the contrary, OECD countries decrease the impact of capital and add more (strong) co-innovation.

On what refers to the differential of the growth of productivity it is important to note that all countries used co-innovation, but in the first stages it had a negative impact on the general growth of the economy, turning positive in the last stage.

Conclusions: Evidence of the existence of new sources of productivity: ICT, human capital, institutions, innovation. In LatAm, though, institutions and Internet are not very important to explain productivity. Thus, the lack of presence of such productivity sources in LatAm explain the difference of growth of productivity between LatAm and OECD countries.

It is important to note that ICTs do not act alone in impacting productivity, but require other factors such as human capital, organization or institutions. Same can be said about the other factors, such as institutions.

Discussion

Jorge Sainz: how can we tell the quality of education by the indicators chosen (only “input”-type of indicators were chosen, and not “output”-type)? Would quality have an impact in the conclusions of this research? Do Caribbean countries behave as the rest of the LatAm region countries or are they different?

Luis Chaparro: in LatAm, most introductions of ICTs have addressed the automation and substitution of old technologies, but not the rethinking of the whole process of production. This is absent in the research, but very much in agreement with the results shown in it.

Josep Coll: beyond human capital, the consideration that countries have to their peoples (trust in people, for instance; management vs. leadership; value sharing, etc.) sure also has an impact on innovation and productivity. Same applies to culture: LatAm, Asia or OECD countries have major cultural differences that surely affect efficiency, productivity, the very concept of growth or welfare, and they should thus be added to the models. And, usually, efficiency gains have a trade-off with other factors, usually rooted in culture: hence, what are these cultural factors that people are willing to trade for higher rates of efficiency?

Darío Quiroga: the inclusion of the quality of education there was an attempt to add it to the model, but it is very difficult to find data on the topic Indeed, there is a dire need for universities in the region to reflect about this topic, and how to measure/quantify it. On a related topic, it is also true that there are many other “qqualitative” differences such as fixed phone lines vs. mobile telephony, or, within mobile telephony, GSM or 3G. A commitment thus, has to be made and accept that the research will have some limitations, especially at the qualitative level. There is hence a need for other qualitative approaches to complete this research.

Notwithstanding, the role of institutions — mainly a qualitative one — is dealt with in the research and a positive impact is found too.

Related with “retinking one’s business” (RE Chaparro) it is true, but can be proxied by looking at the organizational practices, which was included in this research.

Concerning organizational practices — and more related with people in businesses — LatAm is still showing lack of flexibility and of change within businesses, on changing the way workers are managed or addressed to. So, it seems that culture, change of cultural patterns, change of organization architectures do not seem to be following the path of other issues like the adoption of ICTs in institutions. There is a huge gap between investment and usage of ICTs and knowledge economy in Latin America.