By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 20 August 2018

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

No Comments »

Ants, courtesy of Fabien Cambi

Ants, courtesy of Fabien Cambi

This is a three-part article entitled Fostering non-formal and informal democratic participation. From mass democracy to the networks of democracy.

The first part deals with Man-mass and post-democracy and how democracy seems not to be maturing at all, or even going backwards due to lack of democratic culture and education. This second part deals with the Digital revolution and technopolitics and reflects about how the digital revolution might be an opportunity not only to recover but to update and transform democracy. The third speaks about what kind of Infrastructures for non-formal and informal democratic participation could be put in place.

While we are witnessing this possible exhaustion of democracy, the digital revolution has long ceased to merely affect the management of information and communications to be a vector of very deep transformations in absolutely all aspects of daily life. They do not escape to this revolution neither civic action nor democratic commitment.

There are many and controversial pros and cons on the so-called electronic democracy, the uses and abuses of the practices that we encompass as Government 2.0 or the enormous disagreement on whether the new channels of information and digital communication improve or worsen the quality of the information that arrives to the citizens, or if citizens are able to form part of more pluralistic communities or, on the contrary, they are enclosed in their own resonance chambers.

An issue that seems unquestionable to us, because it transcends the scope of democratic action, is the elimination of intermediaries for many of the collective tasks that traditionally required institutions to promote, articulate, organize, guide and resolve collective action. Or, failing that —the elimination of intermediaries— at least a radical transformation of the roles or actors that will develop these mediation roles.

We believe more than proven by the empirical evidence that the cost of participating in any area of ??collective decision-making has been dramatically reduced. Information, deliberation, negotiation, specification of preferences, decision making in itself, evaluation and accountability. All this can now be done with significantly less material and personal costs than in the past.

Likewise, and as mentioned above, the potential to increase the benefits of participation has also increased due in part to the potential increase in participation itself, but also to the potentially much greater quantity and quality of information for the taking of decisions, the possibility of carrying out simulations, pilot tests, obtaining more and better indicators and in real time, the potential increase of the relative benefit by reducing the cost of conflict management, etc.

These potentials have been materialized in countless citizen initiatives focused on self-organization, self-management, decision-making distributed in what has come to be called for-institutions, spaces of autonomy or means of mass self-communication.

However, the wide range of opportunities offered by these spaces often takes place completely giving their back to institutions. Not only outside of them, but alien to them, when not directly challenging what was previously the natural space of these institutions or even their foundational functions, as Yochai Benkler reminds us.

Even in the case where one believes that institutions were not necessary, an orderly transition between the now hegemonic institutional space towards informal spaces of democratic participation would seem desirable.

Our bet —based on the belief that institutions have many difficult functions to replace, among them and as a priority the protection of minorities— is towards a deployment of the collective action of institutional spaces towards (also) the new informal spaces, as well as a sharing of sovereignty between these same institutions with the new actors of civic action in particular, and citizens in general.

However, we run the risk of falling into what Manuel Delgado calls citizenshism, namely, let citizens participate, but participate just and necessary. To avoid this, we propose a return of sovereignty based on putting the “means of political production” in the hands of citizens.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 18 July 2018

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

No Comments »

Anthill inside, courtesy by Marcel de Jong

Anthill inside, courtesy by Marcel de Jong

This is a three-part article entitled Fostering non-formal and informal democratic participation. From mass democracy to the networks of democracy.

This first part deals with Man-mass and post-democracy and how democracy seems not to be maturing at all, or even going backwards due to lack of democratic culture and education. The second one deals with the Digital revolution and technopolitics and reflects about how the digital revolution might be an opportunity not only to recover but to update and transform democracy. The third speaks about what kind of Infrastructures for non-formal and informal democratic participation could be put in place.

There are two complementary views of citizen participation. The traditional view is that participation helps us to design better laws and public policies thanks to making more people work on them, with different visions and with different knowledge. Thanks to this greater concurrence, we get more effective laws and policies —because their diagnosis and range of solutions are more adjusted— and more efficient, since consensus is increased, conflict is reduced and design is technically better.

This view, which we could describe as essentially technical, can be complemented by another vision much more philosophical or even political in the sense of social transformation through ideas. This second view is that participation of a deliberative nature could constitute a kind of third stage of democracy, taking the best of Greek democracy (direct) and modern democracy (representative), at the same time that it contributes to addressing more and more manifest shortcomings of both: on the one hand, the cost of participating; on the other hand, the increasing complexity of public decisions. However, this third stage, given its deliberative nature, by definition must occur in new spaces and with new actors, to incorporate the current design of democratic practice centered almost exclusively on institutions.

Greek democracy has often been idealized as the perfect paradigm of public decision making: citizens, highly committed to the community, assume the responsibility of managing that public. They inform, debate, make decisions and execute them. Without caricaturizing what was of course a much more elaborate public management scheme, there are at least two aspects that are worth considering. First, the relatively simple sociopolitical context of the time. Second, the existence of citizens of a lesser degree or directly non-citizens (women, foreigners, slaves) on whose shoulders were discharged many tasks that facilitated that citizens with full rights could do politics.

The next reincarnation of democracy will take place several centuries later in a totally different socio-economic reality that will change rapidly on the back of science and the industrial revolution. The modern liberal democracies, given the greater complexity of the context, as well as the greater (and also increasing) concurrence of free citizens, will resort to the creation of the State and the institutions of democratic representation for its administration. The delegation of power will be a radical transformation of the exercise of democracy that in turn will transform social organization —and vice versa.

Some authors, however, alert us both to deficiencies in their design and signs of depletion. Ortega y Gasset, among others, warns in The rebellion of the masses that the technical and social advances have not been followed by similar advances in the fields of ethics or education, understanding education not as technical training for professional development, but in the humanistic sphere of personal development or as human beings. These so-called mass-men, says Ortega, are capable of operating with revolutionary technologies, but have not been able to grasp the historical dimension of humanity and, with this, are unable to understand and even to rule their own destiny. Ortega warns —and his warnings can be complemented by Elias Canetti‘s reflections on the dynamics of mass and power masses— how easy it is to end up controlling these masses, as well as the degeneration of that manipulation that we have come to call fascism.

In a less destructive but equally worrisome version, Colin Crouch describes the current situation of democracy as post-democracy. Crouch explains that the growing complexity of decision-making, as well as political disaffection due to a feeling of alienation and ineffectiveness of politics, expulse tacitly or explicitly the citizens of the public agora, leaving them in the hands of elites who control, with an appearance of democracy, all the springs of public life.

Paradoxically, the “solutions” that have appeared for one case (the mass-man) or for another (the post-democracy) are opposite and complementary at the same time: before a mass-man incapable of ruling himself, one aims for technocracy, for political meritocracy to its limit, for the professional rulers that are above a misinformed and ignorant citizenry, for the political aristocracy as a solution. On the other hand, the fight against post-democracy, the struggle of the elite that “does not represent” the citizen, has often led to populisms where a messianic leader, belonging to the people and not to the reviled elite, stands as foreseer of any solution, easy and simple, and many times consistent in finding a scapegoat to sacrifice along with the corrupt political elite. That populism derives in fascism is, as many authors like Rob Riemen say, only a matter of time.

The question that remains latent, however, is whether there is a middle ground between fascism and aristocracy. It would seem that in this middle term there should be at least two concurrent circumstances: first, to go beyond education based on information and move towards the upbringing of full citizens, in the sense of individuals aware of their social environment and rights and duties towards their peers and their project as a collective; second, to provide instruments so that these trained citizens can democratically express their wishes and needs within this new globalized and complex system and, above all, under the protection of destructive populist drifts or the dispossession of their rights by the aristocracies.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 30 June 2018

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: theory_of_change

2 Comments »

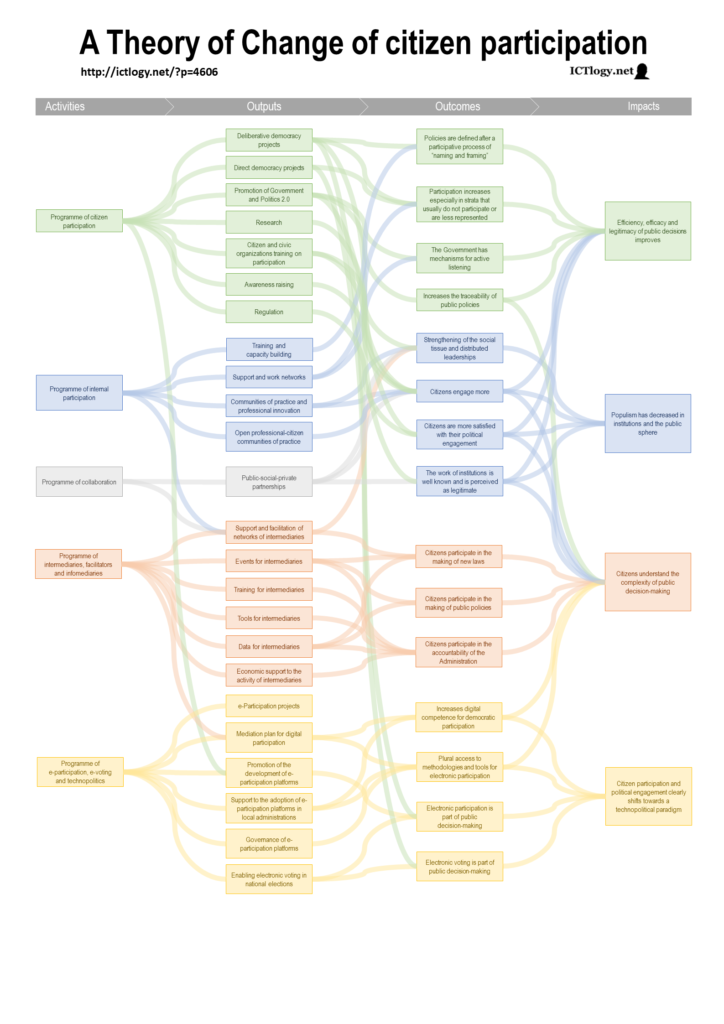

The Theory of Change is a methodology for strategic planning for social change. It is based on a reverse engineering process: once the systemic changes are stated, the process goes backwards to identify what outcomes are related to these systemic changes, what outputs (products, services) lead to these outcomes, and what activities or groups of activities (programmes, resources, etc.) have to be deployed to create these outputs.

What follows is a Theory of Change of citizen participation, in which the engagement of citizens in public decision-making is put at the service of some systemic changes and, reversely, can be fostered through some specific programmes.

The expected impacts, featured on the right side of the scheme above, are:

- Efficiency, efficacy and legitimacy of public decisions improves.

- Populism has decreased in institutions and the public sphere.

- Citizens understand the complexity of public decision-making.

- Citizen participation and political engagement clearly shifts towards a technopolitical paradigm.

The first expected outcome is pretty straightforward and is usually the expected outcome of any citizen participation policy. Second and third are, indeed, the two sides of the same coin, and are related with the quality of democracy in particular and social cohesion in general. The last one, more instrumental, aims at embedding technology not as a mere tool, but as the driver of a deep transformation in how people collaborate with each other and with the Administration: from an institution-centred and hierarchy-articulated collaboration to a people-centred and network articulated collaboration; or, in other words, from centralised to distributed decision-making.

The Theory of Change ends up with —or begins with, depending on how one sees it— five main programmes:

- Programme of citizen participation.

- Programme of internal participation.

- Programme of collaboration.

- Programme of intermediaries, facilitators and infomediaries.

- Programme of e-participation, e-voting and technopolitics.

The first one is the traditional ones: make citizens participate. The second one aims at transforming institutions with the same philosophy: let public servants and politicians participate, work together, open up to the citizens. The third one is putting together the former two: let us see what happens when participation takes place between the two spheres. The fourth one aims at addressing the “industrial sector” of participation, but with a hint: it is not about the firms that facilitate projects, but about the collectives that do, as increasingly it is the organised civil society that engages itself in this kind of facilitation: data and research journalists, activists, hackers, social movements, etc. Last, the fifth one is an explicit support to participation infrastructures, including technology but also the methodologies that are embedded in these technologies.

As this is a draft, a work in progress, comments are more than welcome.

Some references on the Theory of Change

Brest, P. (2000). “

The Power of Theories of Change”. In

Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2000, 47-51. Palo Alto: Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society.

Connell, J.P. & Kubisch, A.C. (1998). “

Applying a Theory of Change Approach to the Evaluation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Progress, Prospects, and Problems”. In Fullbright-Anderson, K., Kubisch, A.C. & Connell, J.P. (Eds.),

New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Theory, measurement, and analysis. Volume 2. Queenstown: Aspen Institute.

Rogers, P. (2014).

La Teoría del Cambio. Síntesis metodológicas. Sinopsis de la evaluación de impacto nº2. Florencia: UNICEF.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 19 June 2018

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: dgpcgencat

2 Comments »

Appointment as Director General of Citizen Participation

Appointment as Director General of Citizen ParticipationOn 19 June 2018 I have been appointed Director General of Citizen Participation at the Government of Catalonia.

Thus, I am now on leave from my position at the School of Law and Political Science at the Open University of Catalonia, to which I shall return when my duties are over at the government.

The Directorate-General of Citizen Participation belongs to the Secretariat of Transparency and Open Government, within the Department of Foreign Affairs, Institutional Relationships and Transparency. I like to explain that the directorate-general I am part of has the responsibility to foster and facilitate the exercise of the “three democracies”, that is:

- Direct democracy: the directorate-general is the responsible for running citizen consultations at the regional level (Catalonia) and helps local administrations to run their own.

- Deliberative democracy: the directorate-general organises deliberative processes related to law-making or policy-making processes, or for better knowing the will of the citizenry in specific issues.

- Representative democracy: the directorate-general is the governmental body behind the organisation of regional elections and collaborates in the organisation of sub-regional elections.

There are four impacts that as a directorate-general in particular, and as a department, we would like to have:

- An improvement in efficiency, efficacy and legitimacy of public decisions improves.

- A decrease of populism in institutions and the public sphere.

- Citizens understand the complexity of public decision-making.

- Citizen participation and political engagement clearly shifts towards a technopolitical paradigm.

During my tenure — expected lasting 4 years —, we are planning to develop six programmes, based on an updated version of this Theory of Change of citizen participation:

- Programme of deliberative participation: to foster and improve projects on deliberative democracy, government 2.0, an appropriate regulatory framework for citizen participation, and awareness raising on the importance of this instrument through training, research and dissemination.

- Programme of electoral participation and direct democracy: to foster and/or improve electoral processes and projects on direct democracy, and awareness raising on the importance of this instrument through research and dissemination.

- Programme of internal participation: to work towards a transformation of how the Administration understands and makes use of collaboration within the government and with the citizens, by means of training and capacity building on participation, networks of support and work, communities of practice of professional innovation, and open communities of practice between public servants and citizens.

- Programme of collaboration: which aims at standardising and normalising public-social-private-partnerships and four-helix type of innovation initiatives.

- Programme of intermediaries, facilitators and infomediaries: to contribute to the growth and consolidation of an expert or professional sector in the field of participation, to achieve the maximum quality in participation practices and projects by bringing onto the sector and engaged citizens knowledge, instruments, technological tools or resources in general.

- Programme of e-participation, electronic voting and technopolitics: to accelerate the adoption of ICTs in the field of participation thus contributing to ease and normalise e-participation, e-voting, e-government and e-democracy in general while, at the same time, transforming the paradigm behind citizen practices based on mostly passive or responsive actors to a technopolitical paradigm based on active, empowered and networked actors.

This is a most ambitious plan. Some of its parts are of course not reachable on a four-year basis. I am quite convinced, though, that one should plan for the long-run, to aim for ideal horizons, and just constraint oneself when it comes to planning the yearly budget. It is evident that intermediate milestones are needed, both to assess the evolution of one’s work as to provide voters with insights about the government’s performance for the due elections without having to wait for, say, 10 years.

But without higher visions there is no transformation possible. And if we want to have an impact, transformation of government in citizen practices is, in my opinion, an absolute need.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 31 May 2018

Main categories: Development, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, ICT4D, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: open_evidence, youth

No Comments »

Study on the Impact of the Internet and Social Media on Youth Participation and Youth work

Study on the Impact of the Internet and Social Media on Youth Participation and Youth workThe Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture of the European Commission has just released the Study on the impact of the internet and social media on youth participation and youth work, that was coauthored by Francisco Lupiáñez-Villanueva, Alexandra Theben, Federica Porcu and myself.

The study analyses 50 good practices and 12 case studies to examine the impact of the internet, social media and new technology on youth participation and look at the role of youth work in supporting young people to develop digital skills and new media literacy

.

In my opinion, the main result of the study confirms what others have already found and that is increasingly becoming the trend in inclusion and development: top-down approaches only do not work, and bottom-up, grassroots initiatives are necessary for projects to work. In other words, weaving the social tissue has to come first for any kind of community intervention one might want to deploy.

The 10 pages of conclusions can more or less be summarised this way:

- Socio-economic status is crucial at the individual level and the knowledge gap has to be addressed immediately before social interventions.

- Enabling the social tissue at the micro level contribute to strengthen the community and thus improve the diagnosis and mobilise social capital.

- As people act in different communities, weaving networks at the meso level makes sinergies emerge and synchronise multilayer spaces. Skills and training are key at this level.

- Once the initiatives have begun to scale up, it is necessary to mainstream and institutionalise them at the macro level, which means fixing them in policies and regulation. Quadruple helix of innovation approaches are most recommended.

- The acquisition of digital skills has to be based on digital empowerment, on a sense of purpose.

- Digital participation and engagement has to aim at being able to “change the system”, to structural changes, to digital governance.

- The now mostly deprecated approach of

build it and they will come

should leave way to an approach in the line of empower them and find them where they gather

. That is, to look for extra-institutional ways that young people participate and engage to design your capacity building and intervention scheme.

Abstract:

The study examines the impact of the internet, social media and new technology on youth participation and looks at the role of youth work in supporting young people to develop digital skills and new media literacy. It is based on an extensive collection of data, summarised in an inventory of 50 good practices and 12 case studies reflecting the diversity of youth work from across the EU. It confirms that youth work has an important role to play, but more has to be done by policy makers at both EU and national level to respond to the challenges and adapt policies in order to foster engagement and active citizenship of young people.

Downloads:

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 08 December 2017

Main categories: ICT4D, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: agroconsumption, cooperativism, nuria_vega, platform_cooperativism, redes.com, ricard_espelt

No Comments »

Consumption groups and cooperatives in Barcelona (article)

Consumption groups and cooperatives in Barcelona (article)Ricard Espelt, Núria Vega and I have just published an article at on consumption cooperatives: Plataformas digitales: grupos y cooperativas de consumo versus La Colmena que dice sí, el caso de Barcelona (Digital platforms: consumption groups and cooperatives vs. The Food Assembly in the case of Barcelona).

The article compares the emergence of agroconsumption groups and cooperatives in Barcelona since the mid 1990s with the most recent appearance of (presumably) platform cooperativism-based initiatives such as The Food Assembly.

The main conclusions are that while agroconsumption groups and cooperatives are deeply rooted in the social and solidarity economy, and most of the times in the sharing economy, some platform-based initiatives not only do not share this principles but, as it is the case of The Food Assembly, they do not even match in what we understand by platform cooperativism.

The article is in Spanish. An abstract in English follows and then the link for downloading the full paper.

Abstract

The cooperative tradition around the consumption of agro-food products has a strong historical background in the city of Barcelona. Even if we refer to the first modern consumer cooperatives, we realize that their task has twenty-five years of permanence (Espelt et al, 2015). More recently —in July 2014— appears in the city another initiative of consumption to facilitate direct sales between local producers and communities of consumers, called food assemblies. Although the origins and differences between models are evident, they both share some common aspects in their approaches —willingness to self-manage, disintermediation of production and building a community—, articulated as part of the so-called “Collaborative Economy”. For their part, both types of initiatives, although with a very different approach, have in technology an important backbone for their activity. In this article, we analyze the points of encounter and discrepancy between the two actors as a model, placing the research framework in the city of Barcelona, where —in March 2017— we located some sixty groups and consumer cooperatives (Espelt et al., 2015) And thirteen food assemblies, six in operation and seven under construction. Emphasizing as differential factors, economic, technical, legal aspects, type of governance, values associated with the model or linked to the relationship between people, producers, final product or space.

Downloads

Ants, courtesy of Fabien Cambi

Ants, courtesy of Fabien Cambi