By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 02 July 2015

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: daniele_quercia, idp, idp2015

No Comments »

Connected New Urbanism. The future of the city is about people

Daniele Quercia, Computer Scientist and Urban Computing Researcher

The debate around smart cities is usually led by technology — and the industry — and not by the citizen.

Smart cities can (or should…) be understood as the study of the dynamics of online networked individuals and use it for the improvement of cities in the future.

Kevin Lynch stated that one’s degree of well-being is highly conditioned by the layout of the city in which one lives, the layout of streets, etc. And it is quite much about visibility: the ease with which each part of a city can be recognized and organized in a coherent pattern.

Stanley Milgram studied what parts of the city were visible and what where not. And he found out, again, that visibility had to do with one’s degree of well-being.

This visibility, or better put, the recognizability was measured through an experiment: Urban Opticon. And we can aggregate peoples visions, how people recognize what places, and put them in the map. That map — actually a cartogram — shows how some places in one city are highly relevant for people’s lives, while other are just “invisible” to most people’s eyes.

What data says is that the more a recognizable a place is, the more correlated its well-being level. There is a high and positive correlation between recognizability and well-being. This is important for policy-making as it may be a good idea to put up initiatives that increase recognizability in order to contribute to the improvement of well-being.

Smells, odours, colours, etc. also help humans in mapping their environment. After analyzing how people tagged colours, or smells on social networking sites, a dictionary of urban smells was created. It was found that there is a high correlation between how some terms were tagged and the reality of the landscape at that given place (pollution, nature, etc.) and, thus, one can draft a map of the city and its assets after what people say in social media.

With social media we can contribute to map the city and, most especially, how people see and live the city.

Discussion

Xavier Campos: can’t these methodologies be used for urban planning? Daniele Quercia: usually not, most architects or urban planners do not use these methodologies. Only after the realization that these methodologies can help in designing projects that will make happier citizens, then maybe architects are more positive about using them.

Clara Marsan: how do you assess the relevance, the significance and representativeness of the data you get from social media? Daniele Quercia: during experiments, some personal data were also asked for, so that biases according to profiles can be corrected. We found out that our data is representative by age, gender and race, but not by professional experience. On the other hand, you can also have filtering techniques to improve the words (the language dictionary) used, to correct biases, etc.

11th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2015)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 31 May 2015

Main categories: Information Society, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: informe_faros

No Comments »

FAROS is the childhood and youth health observatory of the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital, one of the most renowned hospitals specialized in children and youngsters in Spain.

Every year they publish a book — the FAROS report — which deals about a topic of especial relevance for families and carers, helping them to understand it and to address it.

The 2015 edition of the FAROS report its entitled Las nuevas tecnologías en niños y adolescentes. Guía para educar saludablemente en una sociedad digital [New technologies in children and youngsters. Guide for a healthy education in a digital society]. As it can be inferred from the title, the report deals about minors accessing technology, the use of devices, online and videogaming, social networking sites, privacy and security, socialization, etc.

I was kindly invited to write one of the final chapters about the pros and cons of digital life. Unlike the preceding co-authors, my approach is not about one specific point of view or technology, but more panoramic. It tries to bring to the debate that the use of technology is a matter of socialization. And, as such, it does carry embedded the very same advantages and risks of interacting with others. Without fully digital inclusion, one will not be in risk of e-exclusion, but in risk of sheer social exclusion. On the other hand, an inappropriate digital inclusion will be very much like inappropriate socialization, putting us in risk of being abused, be an abuser (or a criminal), lack education opportunities and so on.

My chapter is called El doble filo de la tecnología: una oportunidad de inclusión y un peligro de exclusión [The double edge of technology: an opportunity for inclusion and a risk of exclusion] and can be downloaded as follows.

Lots of gratitude to Olga Herrero for counting me in and making it possible.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 25 March 2015

Main categories: Information Society, News, Writings

Other tags: book_review, journal_of_spanish_cultural_studies, manuel_castells

No Comments »

The Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies has just published a book review that I did on Manuel Castells’ Redes de Indignación y Esperanza (Networks of Outrage and Hope in its English edition).

Unlike most reviews — not my words, but someone else’s — my review is not just a description of what is in the book, but an actual review or, better put, a critique. Not necessarily negative one, mind you, but a reading with at least a critical eye.

In my review — which, by the way, is in Spanish — I begin by telling why the book is relevant and comes at a perfect timing.

Then, I go into debating on of the most important (to me) subjects of Manuel Castells’ trilogy on the Information Society and that the author revisits in his by now latest book: the question of space (or of spaces). Unlike what he did in The Information Age, though, his approach to the concept of space is somewhat changed here, and goes more in the line of what other authors have stated, like John Perry Barlow, William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, Javier Echeverría or Marc Augé.

The paper can be downloaded at the following link, and the bibliography that I used can be accessed after the download section.

Download:

Bibliography:

Alcazan, Monterde, A., Axebra, Quodlibetat, Levi, S., SuNotissima, TakeTheSquare & Toret, J. (2012).

Tecnopolítica, Internet y R-Evoluciones. Sobre la Centralidad de Redes Digitales en el #15M. Barcelona: Icaria.

Stephenson, N. (1992).

Snow Crash. New York City: Bantam Books.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 30 January 2015

Main categories: Information Society, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: manuel_castells, network_party

1 Comment »

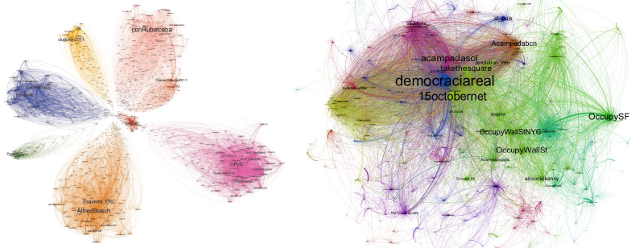

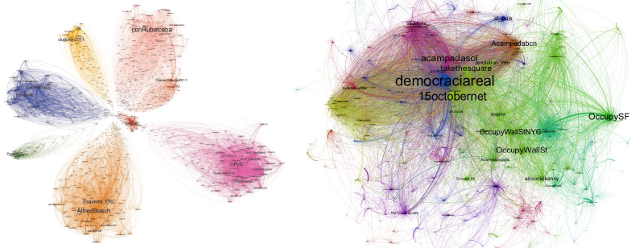

Traditional parties and the 15M movement according to Aragón et al. (2013) and Toret (2013), respectively.

Traditional parties and the 15M movement according to Aragón et al. (2013) and Toret (2013), respectively.Network Society sociologist Manuel Castells has often in his work talked about the concept of the network enterprise. Despite he does not actually provide a formal characterization of what a network enterprise is — or I failed to find one — the concept is very appealing. And is not only appealing when confronting it with aa Taylorist/Fordist model vs. a Kanban/Toyotist model, but because it is an open enough concept (its strength, its weakness) to translate it into other contexts. For instance, politics: is there something like a network party? Are many or some of the new movements that we are witnessing — the Arab Spring, the Spanish indignados, Occupy Wall Street, YoSoy132 — actually more than movements? Are some of the evolutions of these movements — in the case of Spain, Partido X, Podemos, Guanyem — not traditional parties but… network parties?

The network enterprise

Castells, in The Rise of the Network Society, defines the network enterprise as that specific form of enterprise whose system of means is constituted by the intersection of autonomous systems of goals

. This idea of autonomy is essential as, on the one hand, it is one of the consequences of the detachment of the physical constraints once information and communications are digitized and, on the other hand, one of the main causes of the changes in institutions that we will increasingly be witnessing.

This autonomy enables a network made of firms or segments of firms, or from internal segmentation of firms

that now have the project at their core. Projects, not assembly lines, are the operational units around which all actors and resources spin. The project is an independent partnership which can be accountable for its successes and failures, which has its own structure and its own developments.

And yes, projects can interact, leading to corporate strategic alliances and inter-firm networking, but always on the basis of horizontal cooperation. Thus, we leave behind industrialism to embrace informationalism, and we leave behind mass production to embrace flexible production.

Later, in Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society, Castells emphasises that the network enterprise is not about a network of enterprises, but about internal decentralization and partnerships with other firms having as a link, as a connector the project. Through this link, information flows: sharing information is the basis of co-operation. And when the exchange of information is no more needed, the project is dismantled and alliances are over… for that project.

Although not exactly related with the network enterprise, Castells partly depicts the impact of this change in the ways of production in society. In Local and Global: Cities in the Network Societyy, the author speculates on changes to the work-living arrangements which may be coming back to prior-industrial era times, transforming industrial spaces into informational production sites, in ways similar to how craftsmen shared knowledge and expertise.

The network party

So, can we translate these reflections into the political party arena?

I believe most of the aforementioned points can be put side by side in a comparison between traditional parties and (a mostly theoretical approach to) network parties:

| Traditional party |

Network party |

|

Network of (subsidiary) branches.

|

Network of cells, franchises.

|

|

Internal hierarchy.

|

Internal independence.

|

|

Internal centralization.

|

Internal decentralization.

|

|

Information is kept secret, even to insiders.

|

Co-operation based on sharing information, especially with outsiders.

|

|

The unit of production is the programme.

|

The unit of production is the project.

|

|

Hierachic system of procedures.

|

Autonomous system of goals.

|

|

Industrialism.

|

Informationalism.

|

|

Total planning.

|

Open social innovation.

|

|

Fordism:

- Management-worker submission.

- Especialized labor.

- Message control.

- Iincrease control.

|

Toyotism:

- Management-worker cooperation.

- Multifunctional labor.

- Quality control.

- Reduce uncertainty.

|

|

Mass production.

|

Flexible production.

|

|

Inter-firm chain of command.

|

Inter-firm networking.

|

|

Corporate competition.

|

Corporate strategic alliance.

|

|

Vertical cooperation.

|

Horizontal cooperation.

|

|

Party is your life/job.

|

Work-living arrangements, casual participation.

|

How to more thoroughly characterize the network party, and, most important, how to identify what parties and to what degree they share these characteristics is a work that surely needs being done. Especially to test whether any of this is actually true, or if it actually works. But, at least, I believe there is some pattern that strives to match this model.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 11 December 2014

Main categories: Education & e-Learning, Information Society

Other tags: debatseducacio, philipp_schmidt

No Comments »

Social Open Learning: Can Online Social Networks Transform Education?

Philipp Schmidt, Director’s Fellow at the MIT Media Lab

The Internet changed how talent is distributed. And talent is distributed equally, but opportunity is not.

If we take 1088AD as the foundation of the University — the year of the foundation of the University of Bologna —, it is a huge achievement that it has lasted that long, but it also means that there are many tensions piled up along time, as its model has remained mainly unchanged. And engagement seems to be at its lowest levels when we measure lectures, accoding to Roz Picard’s work. When facing the future of education, we should certainly challenge the concept of the lecture.

How do we learn? How do we create an engaging learning experience?

4 Ps of Creative Learning:

- Projects. Does not necessarily mean “building” something, but the idea of setting up a project with goals, processes, tasks, milestones, etc.

- Peers. Sharing, collaboration, support.

- Passion/Purpose. Connection with your personal interests, so you’re engaged by the idea. Attach people to the things they are already interested.

- Play. Taking risks, experimenting, not being afraid to fail.

What about open social learning? We have to acknowledge that most of the “advancements” and “innovations” in education have limited themselves to replicate the actual educational model. Are open social learning communities the future of education?

Open:

- Contribute over consume.

- Peer to per over top down.

- Discover over deliver.

The future of education is not technology. The opportunity of internet is not connecting computers but people. It’s the community what matters.

Success criteria of the MIT Media Lab:

- Uniqueness. If someone is already doing it, we do not do it too.

- Impact. It has to change people’s lives.

- Magic. It puts a smile on your face.

The Learning Creative Learning began as a course and ended up as a community. The course itself enabled community building through individual, decentralized participation. A report on the experience can be accessed at Learning Creative Learning:

How we tinkered with MOOCs, by Philipp Schmidt, Mitchel Resnick, and Natalie Rusk.

Organization of an Edcamp in the line of barcamps or unconferences, but online, using Unhangouts. Unhangouts leverages on Google Hangouts, enabling splitting in several “rooms”.

Most of the times, the online experience ended up in several offline meetings, so it’s good to combine both ways of communicating and organizing. On the other hand, the experience proved to be highly engaging, as people would be much more prone to participate.

It’s all about networks and communities.

Discussion. Chairs: Valtencir Mendes

Q: how can you explain why the US is so advanced in learning and, on the contrary, it performs so poor in PISA tests? Schmidt: we should be careful about taking PISA as the measure for everything. That said, there’s a huge problem of underinvestment in public schools and universities, thus the bad scores.

Ismael Peña-López: when we talk about MOOCs, and most especially cMOOCs, we usually find that participants have to be proficient in technology, have to know how to learn, and have to have some knowledge on the discipline that is being learnt. The intersection of these three conditions usually leaves out most of the people. How do you fight this? Schmidt: there does not seem to be a single solution to scaling cMOOCs, and maybe one of the solutions is to take some compromises while keeping the philosophy of the cMOOC. For instance, use some common technologies even if they are not the best ones or the preferred by the leaders. Stick to few tools, good (somewhat centralized, planned) moderation, etc.

Q: how this specific example influenced schools? Schmidt: Learning Creative Learning courses was a course for teachers. That was a way to infiltrate schools from the backdoor. Same, for instance, with Scratch, which is used widely and carries embedded most of the philosophy of the MIT Media Lab.

Q: people usually neither like nor know how to work in groups or collaboratively. If groups work it usually is because there is a strong leader. How do you do that (leading or setting up a leader). Schmidt: we know some of the reasons why groups do not work. But the solution may not be that there needs to be a leader, but leadership. And this leadership can take different forms. Facilitation, the group fabric, etc. can be ways to approach the point of leadership.

Valtencir Mendes: how can we assess and certify what is being learnt this way? Are open badges a solution? Schmidt: certification is very important, as most of the people that approach these initiatives already have a degree. How do we reach people that are looking for a certification and would never participate in such initiatives unless they issue certificates? Communities are extremely good at figuring out who is good at what, who you go to ask a question, etc. Portfolios, portfolios of the projects they have done and the network of people you’ve been working with. Last, the monopoly of certification may have been a good idea in the past, but it may already not be a good idea any more, and it would be better many more ways to get/issue a certificate.

Q: how do you work with soft skills, how do you introduce open social learning in the corporate world to learn these skills? Schmidt: some things are very difficult to teach, but are easy to learn. Many of these soft skills are easy to learn if you create the appropriate context, even if they would be very difficult to teach. But it still is a very hard to solve problem.

Q: can these initiatives work in crosscultural contexts? Schmidt: this is a very complex question. For instance, authority if very related with culture: how do you manage authority in a crosscultural setting? Or, for instance, addressing elder people is differently regarded depending on the culture. So, there are no systems to support crosscultural learning and thus we have to see it case by case.

Josep Maria Mominó: are we now witnessing the end of the hype of technology in education? did we have too much expectations and we now see the impact is poor? Or what will come in the future? Can we really trust the initiative of teachers? Will that suffice? Schmidt: we usually have to wait a whole generation to see impacts in society, and this generation is just now coming of age. On the other hand, we should be expecting not a technology driven change, but a socially driven one. And this may already be happening.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 November 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: 15m, joan_subirats, simona_levi, technopolitics, tecnopolitica14

No Comments »

Joan Subirats (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

Political evolution from the 15M (2011) to the 25M (2014). A political science approach.

Traditional politics is not prepared for this upcoming change. There is no space for public affairs outside of the State. The approach is that of the homo economicus: politics as a market. Democracy is based on rules, not values: elections based on competitiveness, the winner takes it all, etc. Legitimacy is a mix of ideology and being functional in delivering services and welfare to the citizens.

And political science has a Fordist approach to this phenomenon, mainly based in an economicist approach or point of view.

On democracy: from the 15M to the 25M the frame upon which democracy is based has been broken. As this is the frame put into practice by the main political actors at the international levels, these actors have suffered a legitimacy shock. There is an attack to rules from the field of values.

A second major change is the confluence of new actors in the political arena. Constitutions had set who could participate in politics (i.e. institutions) and now new actors are vindicating taking part in politics. And taking part in politics from outside of institutions, which is, again, a dire change: there used to be no politics outside institutions, and now citizens are claiming public affairs as something which is theirs, and not the institutions’.

Participation is understood as doing, as acting. If institutions cannot deliver, citizens will organize, self-organize, and just do it. People won’t accept intermediation in politics, boosted by a powerful technological aspect.

There is the perception that the powers do not represent people because (1) they are not defending the interests of people, (2) because the political elites do not actually live like the people that they are supposed to represent and (3) because, all in all, the are actually taking no decisions. This is a triple breaking of the contract signed between representatives and citizens.

When institutions, the ones that are present in them, do not represent the ones that are absent, something is wrong. Especially when those who are absent, thanks to technology, could actually be present. The 15M makes it possible that the “nobodies” can take a leading role in politics, that they are relevant actors in the political arena, in the process of decision-making on public affairs. And this participation can take multiple shapes and be reshaped: we can change our identities, our networks, depending on our often changing interests.

From collective action to connective action. The 15M is not a movement, but a process of social connectivism (vs. the social constructivism that used to be). Processes are as important and results (or even more). And this is a new paradigm that separates the ones that do politics with the Internet and the ones that do politics on the Internet. Indeed, accepting the logic of the Internet means denying the logic of the party.

Simona Levi (X.net)

Political evolution of the 15M: the creation of 15MpaRato and the Partido X as examples. XXIst century democracy and myths about digital participation.

The 15M is completely alive and the first effects are already taking place, e.g. the end of bipartidism (the hegemony of the Socialist Party and the Popular Party).

The 15M is both a destitution and a constitution process, due to dis-intermediation of organization, information, etc. One can reach autonomy by practicing it, and this is what the 15M is doing: practicing new ways of political commitment and participation.

The 15M is a good remixing device. The 15MpaRato succeeds in remixing old existing things (e.g. fundrising) but in new ways (e.g. crowdfuding)

The Partido X places itself in the future and tries to bring to the present the view of what could be — and maybe should — and proposes a destituent process where institutions are emptied of content, and be filled with the civil society and their aspirations. It tries to make compatible a horizontal approach to participation and the need for a vertical structure that can challenge the established powers.

The frontal attack to corruption in Spain has become the flagship of the destituent part of Partido X: getting rid of old structures by getting rid of old practices (and old practitioners). While the constituent part is Democracy Period.

The Partido X believes that forking is not dividing strengths, but multiplying the fronts from which to attack a common enemy. Democracy is not agreeing on everything, but being able to live one with the other in disagreement.

This does not mean that we do not need professionals in politics: we do need them, we do want professionals in politics. The issue is not that they are “normal” people (i.e. not professionals, people like you and I) but how to control them, how to make their decisions transparent and accountable.

Transparency is not about telling absolutely everything, but opening up the “code”, the possibility to track decisions, to replicate them, to evaluate each and every step.

Discussion

Q: how these political revolutions relate with the commons? Joan Subirats: there are three different fields (1) environmental sustainability, (2) the collaborative economy and (3) the digital commons. The first one has been deeply analyzed by Elinor Ostrom; the second one is about to be discovered, but there are already very good initiatives about it. Concerning the digital commons, while Jeremy Riffkin’s idea of marginal cost zero can be discussed, it is a good approach. An even better approach is Harvey’s approach to scalability. All in all, the central idea is that we should not surrender everything that is public to what is institutional, the state-centrism.

Pablo Aragón: how to build things economically? is all about crowdfunding? Simona Levi: it is not as much about raising money, but about being responsible of one’s actions, about leading them, about making real feasible proposals.

Javier Toret: taking the power or distributing the power? Joan Subirats: the key is representation by action, entering politics by doing things, by delivering, by actually representing the citizen.

Q: what happened with the Partido X? Simona Levi: the Partido X is in the future and speaks from there

. The Partido X has leapfrogged a phase, the institutional one, which is the one that other new parties like Podemos or Guanyem are now following, channelling new messages to set up the destituent phase.

Network democracy and technopolitics (2014)