By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 29 October 2016

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: decidim.barcelona, it_for_change, mavc, technopolitics, voice_or_chatter

No Comments »

This research is part of the Voice or Chatter? Using Structuration Framework Towards a Theory of ICT Mediated Citizen Engagement research project led by IT for Change and carried on under the Making All Voices Count programme.

The research began in May 2016 and is about to end by January 2017.

The project consists in analysing several cases of ICT mediated citizen engagement in the world, led by governments with the aim to increase participation in policy affairs.

This subproject deals with the case of decidim.Barcelona, an ambitious project by the City Council of Barcelona (Spain) to increase engagement in the design, monitoring and assessment of its strategic plan for 2016-2019.

These specific pages focus on the socio-political environment where this subproject takes place, specifically speaking Barcelona, Catalonia and Spain, for the geographical coordinates, and for the temporal coordinates the beginnings of the XXIst century and most especially the aftermath of the May 15, 2011 Spanish Indignados Movement or 15M – with some needed flashbacks to the restauration of Democracy in 1975-1978.

The working paper Technopolitics, ICT-based participation in municipalities and the makings of a network of open cities. Drafting the state of the art and the case of decidim.Barcelona, thus, aims at explaining how and why such an ICT-based participation project like decidim.Barcelona could take place in Barcelona in the first months 2016, although it will, of course, relate to the project itself every now and then.

Dowloads

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 21 August 2016

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, Development

Other tags: mirela_fiori, technopolitics, urbanism

No Comments »

Singing in the rain, courtesy streetwork.com

Singing in the rain, courtesy streetwork.comMy colleague Mirela Fiori is redesigning the Master in City and Urbanism which she is directing. In the updated version that she is planning she wants to include a subject on how technology and civic action have a role in the shaping of the city.

In my opinion this is a most important acknowledgement. Adolfo Estalella and Alberto Corsín have systematically proved how the city can be used both “hardware”, much in the line of Gidden’s Structuration Theory where the “system” is both an instrument and a target for change. Manuel Castells also speaks about cities and their (different) role in the Network Society, a role that oftentimes is emergent in the sense of Steve Johnson. In newest “open source” cities, action turns into activism and activism cannot be without action.

Thus, it does look very relevant to me that there is a little time or space to think about the city not as a mere receptacle of people doing things, but as an actor that is both affected and affecting the uptake of technology and its use for citizen action and, thus, being part of the (new) definition of citizenship.

The goal of the master’s new subject Technopolitics, networks and citizenship is to provide this vision of the city as an institution, a player that requires a renewed strategy and a renewed vision on its role in a complex ecosystem.

My preliminary syllabus (it does not even deserve that name yet) would include the following topics — comments welcome:

Digital revolution and globalization

How dire are the changes we are witnessing in the global economy? How are connected the new trends in the business and financial spheres with the democratic and governance spheres? Are Information and Communication Technologies instruments for improvement or for transformation? Is this a revolution? Why are some things happening? Why would they last — if they do?

Limits of the institutions of the industrial age

Is there a crisis in industrial age institutions (schools & universities, political parties and parliaments, firms and work, media and journalism, etc.)? What is their role in society? Is their role still needed? Can we separate the continent (institutions) from their content (role, tasks)? If yes, who will take up with these roles? How? Why? Why not?

Hacker ethics, commons and gift economy

Is there a new way to design collective initiatives? Is decision-making over as we knew it? Are hierarchies a thing of the past? Is information still power? Can we shift power balances? How different is information from knowledge? How different is controlling information from controlling knowledge? How will the control of knowledge transform our daily practices? And our institutions?

Social innovation, open innovation and open social innovation

What used to be innovation? What is innovation today? What is the relationship between innovation, knowledge and power? Can innovation be distributed? Can innovation be socialized? Can power be socialized? Can innovation lead to better governance? Can better governance lead to innovation? Should we act in either or another way to affect the final result? Can we?

Technopolitics, cooperation platforms and network-organizations

How is technology (ICTs) changing human behaviour? How is technology (ICTs) changing human collective behaviour? What are the main trends? How will they evolve? Why? What new organizations will come enabled (and fostered) by technology? How will this change the map of actors and institutions in society? How will they interact? How will this change the city landscape?

Yes, these are questions and not answers. Because there are not many answers — yet. And the ones being are constantly changing and evolving. But the questions will remain for much longer. These are days for good questions and for flexible answers. Dogmatic answers for feeble questions will rarely help us to map the new territories that need being explored.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 24 May 2016

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: can_kurban, idp2016, maria_haberer, proceedings, technopolitics

No Comments »

What is technopolitics?. There are many definitions (or attempts to define), approaches, contexts. But the truth is that the concept is gaining momentum and catching the attention of scholars. Since the publication of Jon Lebkowsky’s TechnoPolitics and Stephano Rodotà’s Tecnopolitica, both in 1997, the topic has seen an increase of popularity.

Can Kurban, Maria Haberer and I have made an attempt to define an conceptualize the term at What is technopolitics? A conceptual scheme for understanding politics in the digital age which will be presented at the conference IDP2016 – Internet, Law and Politics. Building a European digital space, organized by the School, Open University of Catalonia, and taking place in July 7-8 2016 in Barcelona (Spain).

We here share a pre-print version of our communication, before the last, official, one comes out with the proceedings of the conference.

Abstract

In this article, we seek to revisit what the term ‘technopolitical’ means for democratic politics in our age. We begin with tracing down how the term was used, and then transformed through various and conflicting uses of ICTs in governmental, civil organizations and bottom-up movements. Two main streams can be distinguished: studies about internet-enhanced politics, labeled as e-government and Politics 2.0 that imply facilitating the existing practices such as e-voting, e-campaign, and e-petition. The internet-enabled perspective on the other hand builds up on the idea that ICTs are essential for the organization of (or organizing of) contentious politics, citizen participation and deliberative processes. Under a range of labels studies have often used concepts in an undefined or underspecified manner for describing their scope of investigation. After critically reviewing and categorizing the main literature towards concepts used for describing ICT-based political performances, in this article we construct a conceptual model of technopolitics: A schema consisting of the six dimensions context, scale, direction, purpose, synchronization, and actors systematizing informal and formal ways of political practices. In the following section we explain the dimensions by real-world examples to illustrate the unique characteristics of each technopolitical action field and the power dynamics that influence them. We conclude by arguing how this systematization will help facilitating academic research in the future.

Dowloads

Full paper:

Kurban, C., Peña-López, I. & Haberer, M. (forthcoming). “

What is technopolitics? A conceptual scheme for understanding politics in the digital age”. In Balcells, J. et al. (Coords.),

Internet, Law and Politics. Building a European digital space. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Internet, Law & Politics. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, 7-8 July, 2016. Barcelona: UOC-Huygens Editorial.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 22 May 2016

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: barcelona_en_comu, idp2016, maria_haberer, proceedings, technopolitics

No Comments »

Maria Haberer and I will be presenting our latest communication, Structural Conditions for Citizen Deliberation: A Conceptual Scheme for the Assessment of “New” Parties, also at IDP2016 – Internet, Law and Politics. Building a European digital space, organized by the School, Open University of Catalonia, and taking place in July 7-8 2016 in Barcelona (Spain).

Its content will be quite similar to what we presented at CeDEM2016 in Krems, Austria, though this version has been improved with the comments from the attendants of this conference and, of course, the reviewers of IDP2016.

A pre-print of the paper can be downloaded below. Note that some minor issues can differ from the final version to be published in the proceedings of the conference.

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to elaborate a conceptual scheme for assessing deliberative spaces within political parties that propose the direct input of citizens in policy-making as a possible solution for the crisis that representative democracy is facing. Theory on deliberative democracy has long been concerned with the question on how to assess the structural conditions for deliberation and the advantages deliberation has for the democratic process. Building on existing dimensions, we used a qualitative research design with data from observation, interviews and document analysis to investigate a neighbourhood group of “Barcelona en Comú” (BComú). This recently formed political party experiments with the incorporation of horizontal decision-making practices facilitated through ICTs to establish modes and bodies for citizen deliberation. We discovered relevant themes that allowed us to develop a conceptual scheme when critically assessing deliberative structural conditions. This scheme can serve as a map and a monitoring device for evaluating the actual practice of parties that claim to engage in citizen deliberation. We conclude by indicating the performance of BComú and by asking if the successful implementation of deliberative spaces can lead to a new party model and new trends in political practice including recommendations for further research.

Dowloads

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 21 May 2016

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, News, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism, Writings

Other tags: barcelona_en_comu, cedem2016, maria_haberer, proceedings, technopolitics

No Comments »

Maria Haberer and I have presented a communication, Structural Conditions for Citizen Deliberation: A Conceptual Scheme for the Assessment of “New” Parties, at CeDEM2016 – International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government 2016, organized by the Danube University Krems and that took place in May 18-20 2016 in Krems, Austria.

The research is a first approach to the phenomenon of the “network party” (or net-party) — though we are cautious about the naming and prefer so far a more neutral “new party” — and analyzes the case of Barcelona en Comú, the party now in office in the municipality of Barcelona and whose origin is deeply rooted in the 15M Spanish Indignados movement and other recent social movements with a strong technopolitical profile. The approach takes deliberation as the core around which all the organization spins while transitioning from a social movement to a (traditional?) political party.

Below can be found and downloaded the slides and full text of the communication.

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to elaborate a conceptual scheme for assessing deliberative spaces within political parties that propose the direct input of citizens in policy-making as a possible solution for the crisis that representative democracy is facing. Building on existing dimensions, we used a qualitative research design with data from observation, interviews and document analysis to investigate a neighbourhood group of “Barcelona en Comú”. This recently formed political party experiments with the incorporation of horizontal decision-making practices facilitated through ICTs to establish modes and bodies for citizen deliberation. We discovered relevant themes that allowed us to develop a conceptual scheme when assessing deliberative structural conditions. This scheme can serve as a map and a monitoring device for evaluating the actual practice of parties that claim to engage in citizen deliberation. We conclude by indicating the performance of Barcelona en Comú and by asking if the successful implementation of deliberative spaces can lead to a new party model and new trends in political practice.

Slides

Dowloads

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 15 January 2016

Main categories: e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: network_party, new_politics, technopolitics

1 Comment »

It is difficult to put out a definition of the network party. Maybe — or mainly — because it is much a theoretical construct that does not exist purely in the real world. Any kind of human organization can be characterized, but it will rarely fit the theoretical model: the world is a world of grays.

New politics, technopolitics and political parties

The Spanish 15M Indignados Movement — and everything that came before it — brought new ways of organization which, later on, some of them, entered the political institutions. 2015 saw witnessed three important elections in Spain — municipalities, the Catalan Parliament, and the Spanish Parliament — to which some new and not-so-new parties concurred. A recurrent debate between new and traditional parties was whether these parties, respectively, were doing “new politics” or “old politics”.

One way to define “new politics” was that “new parties” were putting in the political agenda the quality of democracy, sometimes labelled as the “regeneration axis” (in addition to the social or right-left ideological axis). Little to be mentioned here. I personally believe that defending this new axis is a necessary but not sufficient condition or characteristic of new politics.

Another way to define “new politics” was that some political parties were assembly-based. That is, decisions are made at the grassroots level, in the party’s general assembly, and the representatives of the part translate them in the institutions.

In my opinion, this is not only not new politics, but totally misleading to what technopolitics is bringing to the political arena.

First of all, while unheard in most Western democracies, assemblies are anything but new. To say the least, they date from the late XIXth century. This is neither bad nor good: it is just not new.

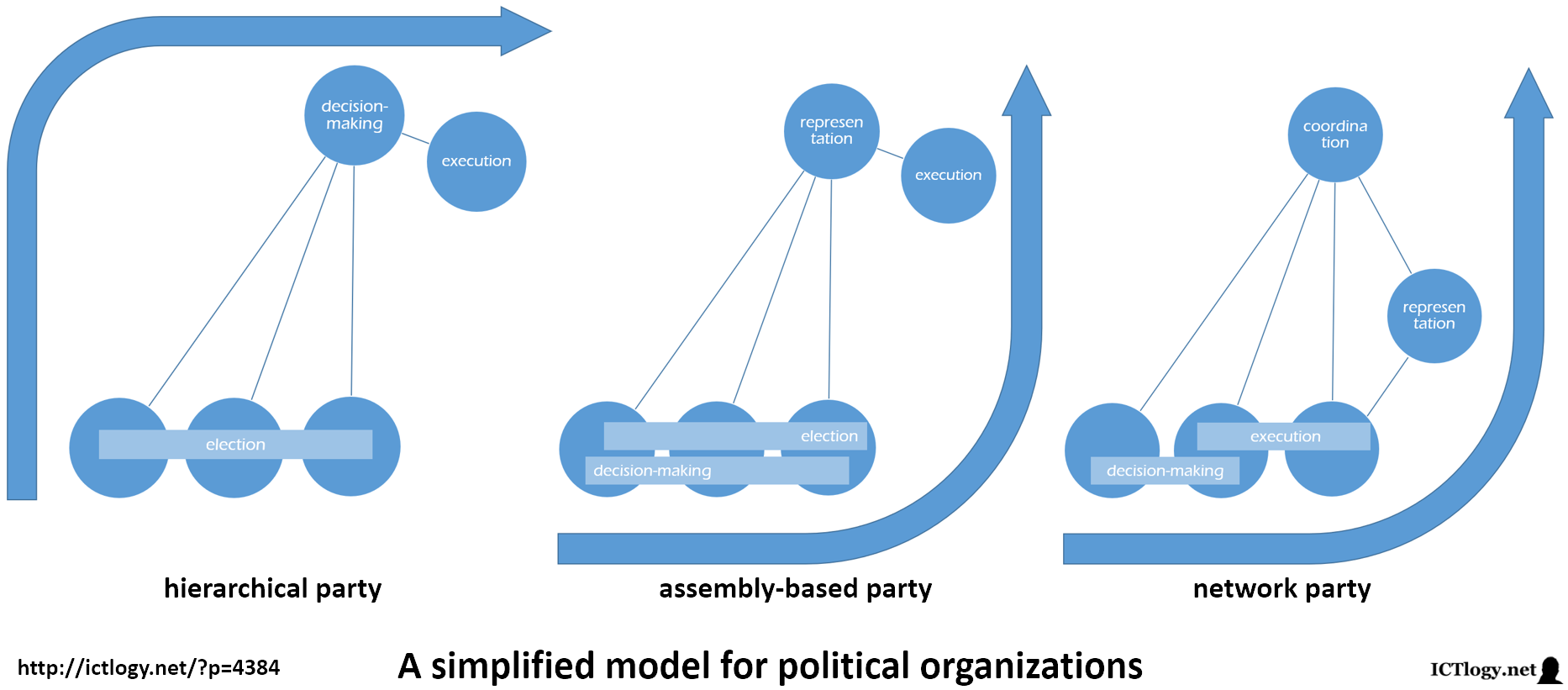

Second, assemblies might by a part of new politics — or, better put, network parties — but the tool does not make the thing. Following, we will try to describe how three different organizations work: hierarchical parties, assembly-based parties and (despite the difficulty to come up with a proper definition) what a theoretical approach to network parties would look like. Please bear in mind what was said above: theoretical models of organizations do not aim at describing how specific organizations should be or work like, but to understand why the are or work the way they do. In a world full of greys.

Hierarchies

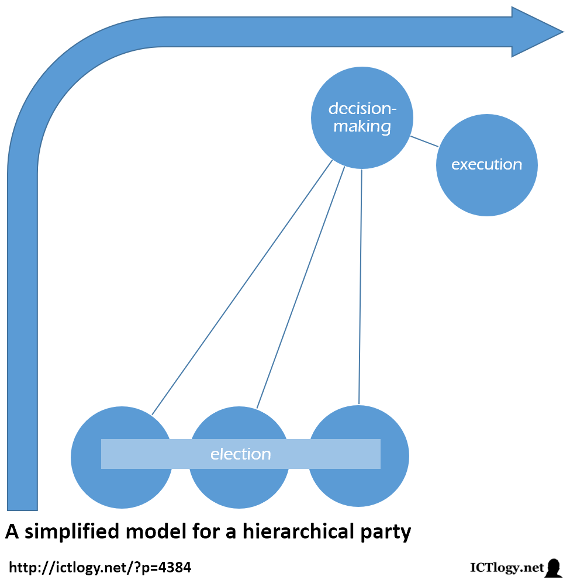

Let us propose a very simplified model where only three things occur: electing representatives, making decisions and executing them.

In a hierarchical party, most things happen in the upper layer of the organization: the lower layer elects their representatives (a secretary general, a secretariat, an executive committee, etc.) and, most of the times, remains outside of the general dynamics of the party.

The elected representatives, though, make all decisions and directly or indirectly execute them. Most of the times too — sad as it may sound — these elected representatives do not even inform the members and sympathisers of the party of the decisions made, and of course very rarely consult them on any issues at all.

At the end of the political cycle, the representatives are accountable for their successes and failures and can be replaced depending on their performance — usually measured in votes or seats, and not in the programme they put out and the actions they took (tough, of course, both of them had an impact that translated in votes, seats, laws passed, etc.).

Assembly-based parties

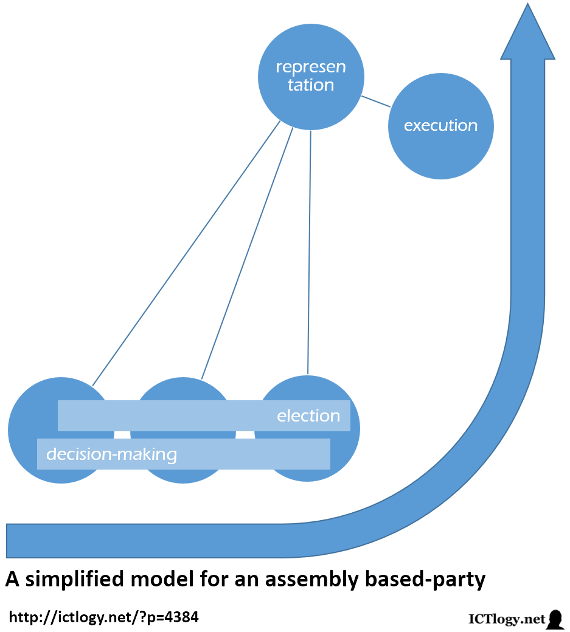

Assembly-based parties work almost opposite than hierarchical parties: the assembly meets, deliberates and makes a decision. Then, once the decision is made, the assembly elects some people that will carry on with the decision and put it into practice.

Oftentimes, these parties have to engage in conversations with other parties, translate the decision into an institution, or simply speak to the media. It is then usual that the same elected representatives emerging from the assembly also play the role of representing the assembly before third parties.

Note how the pair electing-deciding is inverted: if hierarchies elected people to decide what to do it and do it, assemblies decide what to do and elect the ones that will do it.

As we have already said, things in the real world are much more messy and much less clean. But, in simple lines, this is more or less how it theoretically works.

Network parties

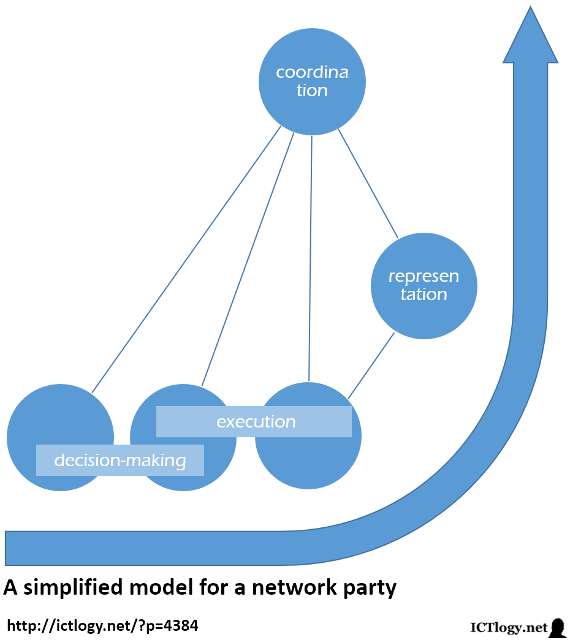

Network parties also invert a pair of steps, but it is not electing of deciding, but executing: in network parties, executing comes first. How is that possible?

Levy, Himanen, Raymond or Benkler, among others, have explained with details the logics of free software and how they can be translated into other knowledge intensive projects. Like, for instance, politics.

In a gift economy, powered by meritocracy and led by do-ocracy people just can set the snowball rolling. If it catches, people will join and the idea, the project, will grow and become important. Otherwise, the idea will be tacitly abandoned and people will move onto other ideas and projects to join and contribute to.

In (pure) technopolitics, network parties emerge from people making decisions first and then executing them. If the projects grow and communities form, then comes the need for some coordination, for some “benevolent dictator” that may coordinate the efforts, make some punctual decisions. These coordinating person or body is elected by the participants on the project, either tactitly — based on her own merit — or explicitly, if there is a need to.

Sometimes the coordinating body will, as it happened with the assembly-based organizations, play the role of representing the collective. But sometimes it will not, as the collective will also have a collective identity and thus will represent itself without the need of intermediation from a specific body.

Following we can see the three (simplified) models for better comparison. It is worth noting how both assembly-based parties and network (or technopolitics-based) parties invert the relationships of power, bringing the decision-making to the bottom — and unlike traditional or hierarchical parties, which have decision-making at the top. But a crucial difference between assembly-based parties and network parties is where execution happens: in network parties, not only decision-making but also execution is distributed and takes place at the bottom. And this is what makes politics new: not only where decision-making takes place, but also where execution does.

As it has been said, these are “elements rarely found as pure substances”, that is, theoretical (and very much simplified) models whose aim is neither saying how things should work, nor how all parties can be distinctively and exhaustively categorized. On the contrary, we may find parties whose inner structure follows a different model depending on the stage, the level at which is is analysed, or even the time or specific task being developed. Thus, it is unlikely to find a party or an organization that perfectly fits the theoretical model, as it is likely to find many parties and organizations that embed in their organizational and operational design several bits of these models. Depending on which one prevails, or leads the culture of the organization, we will be able to generically label them one way or the other.