By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 17 July 2014

Main categories: Education & e-Learning, Knowledge Management

Other tags: ple

4 Comments »

Working in the field of open social innovation, and most especially when one considers institutions as platforms for civic engagement, it is almost unavoidable to think of the personal learning environment (PLE) as a useful tool for conceptualising or even managing a project, especially a knowledge-intensive one.

Let the definition of a PLE be a set of conscious strategies to use technological tools to gain access to the knowledge contained in objects and people and, through that, achieve specific learning goals

. And let us assume that a knowledge-intensive project aims at achieving a higher knowledge threshold. That is, learning.

The common — and traditional — approach to such projects can be, in my opinion, simplified as follows:

- Extraction of information and knowledge from the environment.

- Management and transformation of information and knowledge to add value.

- Dissemination, outreach and knowledge transmission.

These stages usually happen sequentially and on a much independent way one from another. They even usually have different departments behind.

This is perfectly valid in a world where tasks associated to information and communication are costly, and take time and (physical) space. Much of this is not true. Any more. Costs have dropped down, physical space is almost irrelevant and many barriers associated with time have just disappeared. What before was a straight line — extract, manage, disseminate — is now a circle… or a long sequence of iterations around the same circle and variations of it.

I wonder whether it makes sense to treat knowledge-intensive projects as yet another node within a network of actors and objects working in the same field. As a node, the project can both be an object — embedding an information or knowledge you can (re)use — or the reification of the actors whose work or knowledge it is embedding — and, thus, actors you can get in touch trough the project.

A good representation of a project as a node is to think of it in terms of a personal learning environment, hence a project-centered personal learning environment (maybe project knowledge environment would be a better term, but it gets too much apart from the idea of the PLE as most people understands and “sees” it).

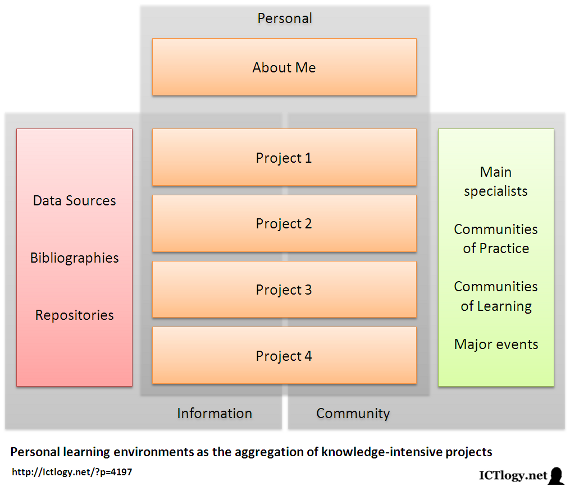

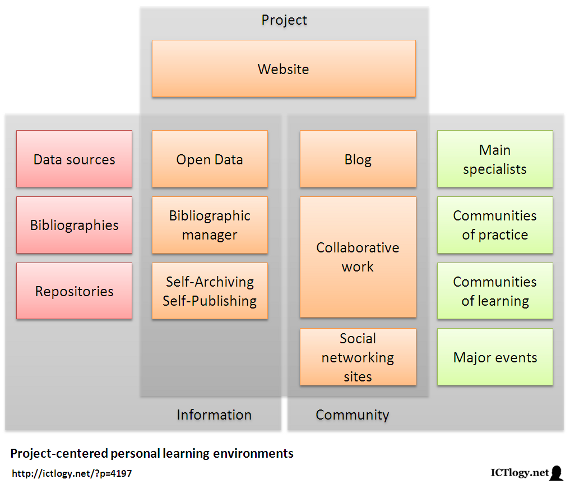

A very rough, simple scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment could look like this:

Scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment

Scheme of a project-centered personal learning environment

[Click to enlarge]In this scheme there are three main areas:

- The institutional side of the project, which includes all the data gathered, the references used, the output (papers, presentations, etc.), a blog with news and updates, collaborative work spaces (e.g. shared documents) and all what happens on social networking sites.

- The inflow of information, that is data sources, collections of references and other works hosted in repositories in general.

- The exchange of communications with the community of interest, be it individual specialists, communities of learning or practice, and major events.

These areas, though, and unlike traditional project management, interact intensively with each other, sharing forth information, providing feedback, sometimes converging. The project itself is redefined by these interactions, as are the adjacent nodes of the network.

I can think at least of three types of knowledge-intensive projects where a project-centered personal learning environment approach makes a lot of sense to me:

- Advocacy.

- Research.

- Open social innovation (includes political participation and civic engagement).

In all these types of project knowledge is central, as is the dialogue between the project and the actors and resources in the environment. Thinking of knowledge-intensives projects not in terms of extract-manage-disseminate but in terms of (personal) learning environments, taking into account the pervasive permeability of knowledge that happens in a tight network is, to me, an advancement. And it helps in better designing the project, the intake of information and the return that will most presumably feed back the project itself.

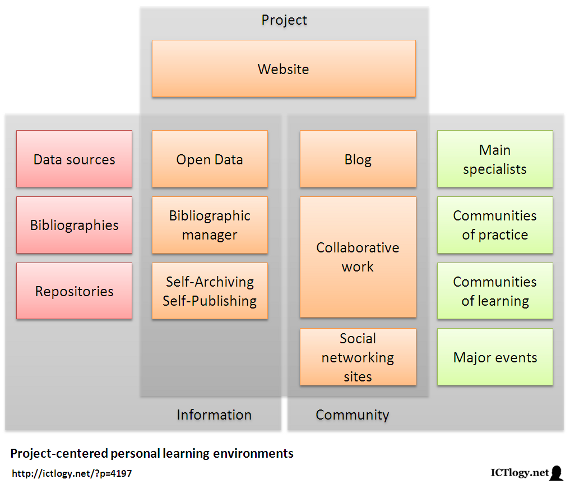

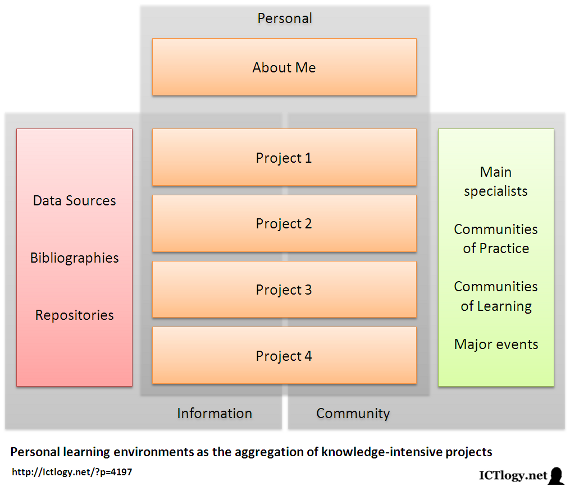

There is a last reflection to be made. It is sometime difficult to draw or even to recognize one’s own personal learning environment: we are too used to work in projects to realize our ecosystem, we are so much project-based that we forget about the environment. Thinking on projects as personal learning environments helps in that exercise: the aggregation of them all should contribute in realizing:

- What is the set of sources of data, bibliographies and repositories we use as a whole as the input of our projects.

- What is the set of specialists, communities of practice and learning, and major events with which we usually interact, most of the times bringing with us the outputs of our projects.

Scheme of a personal learning environments as the aggregation of knowledge-intensive projects

Scheme of a personal learning environments as the aggregation of knowledge-intensive projects

[Click to enlarge]Summing up, conceiving projects as personal learning environments in advocacy, e-research and open innovation can help both in a more comprehensive design of these projects as in a better acknowledgement of our own personal learning environment. And, with this, to help in defining a better learning strategy, better goal-setting, better identification of people and objects (resources) and to improve the toolbox that we will be using in the whole process. And back to the beginning.

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 July 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: francisco_jurado_gilabert, idp, idp2014, javier_peña, rosa_borge

No Comments »

Chairs: Joan Balcells Padullés. Lecturer, School of Law and Political Science (UOC).

Are Social Media changing party politics? Brokers among the members of the Catalan Parliament Twitter Network.

Marc Esteve i del Valle, PhD student on the Knowledge and Information Society Programme at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). Researcher at the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute (IN3); Rosa Borge Bravo; Associate Professor of Political Science at the UOC and researcher at the IN3

When looking at the political usage of Twitter in political parties, it is noticeable that it’s not the leaders but other members of the party the most active on Twitter. Are we before the appearance of ‘brokers’ that bridge different political clusters?

H1: Given the high density of the Catalan parliamentarians’ Twitter network, its high reciprocity, its clustering structure and the particular working milieu that it reflects, we expect the appearance of structural holes and therefore brokers.

H2: The Catalan parliamentarians who are young, highly educated, highly active on the Internet and parliamentarian works and belong to the ruling party, are more likely to be the bridges of the Catalan parliamentarians’ twitter network.

The dependent variable was the degree of centrality in the network, and as independent variables there were many: socio-economic, political, about your personal network, etc.

Results showed that the Parliament is a not very dense network, but also that it is a close one. It’s a closed and affiliated universe. 26 MP where considered as being brokers. They are not leaders of their respective parties and, indeed, they often neither belong to the mainstream ideology of the party.

We can cluster all the MPs in 4 communities, whose composition changes along time (January to March, 2014).

H1 is corroborated. But H2 is not. For being followed is important to have a blog, to speak a lot at the plenary and to hold a MP position, but there is no relationship with socio-demographic characteristics, no official role at the Parliament, no interventions to the commissions, no tweet intensity, no incumbency, no Internet use.

La desrepresentación política. Potencialidad de Internet en el proceso legislativo.

Francisco Jurado Gilabert, Jurista e Investigador en el Laboratorio de Ideas y Prácticas Políticas de la Universidad Pablo de Olavide. Doctorando en Filosofía del Derecho y Política en el IGOP, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.

We have a context where even the voters think that the Congress or the Senate represents the people… despite the fact that the Law says that it is so. On the other hand, there are other institutions of “direct” participation, which are not actually such, as they require some approvals or backing from the representative institutions.

Political representation is forced: one cannot chose not to be represented by the Parliament (e.g. as one can choose a lawyer to represent them in a trial). Elections are not about being represented or not, but only about somewhat influencing who is going to represent the whole citizenry. Why is it so? Why is the citizenry forced to be represented? There do not seem to be solid reasons to be politically supervised and represented. The only reason being the incapability of gathering everyone together, at the same time and at the same place for decision-making.

And it gets worse: the laws that frame representation are increasingly used as barriers against the entrance of competitors. It is difficult to create a new party or to create a new political platform. Pitkin’s dimensions of representation (1967) are systematically violed: there is no authorization or empowerment, no accountability, no suitability, no symbolic dimension (or just a little bit), no substantive representation of interests.

We need an act of de-representation, of demanding representation back. Maybe not the whole time, but on demand, when it is needed.

And there are many ICT tools that come very handy for that purpose.

MiFirma.com [MySignature] is a non-profit organization to collect signatures to promote certain initiatives. The difference with other petitioning sites is that at MiFirma signatures are electronic and thus legally binding. For instance, formally and officially signing political initiatives.

Setting up the platform is easily in technological terms than in legal terms. One needs and administrative authorisation, the platform has to accomplish some (non-justified) requirements and restrictions on the time of e-signature to be used, etc.

10th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 July 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: idp, idp2014, jose_manuel_perez_marzabal, maria_arias_pou, maria_dolores_palacios_gonzalez, ramon_miralles, zofia_bednarz

No Comments »

Chairs: Miquel Peguera. Senior Lecturer, School of Law and Political Science (UOC).

The modification of the Spanish RDL 1/2007 de 16 de noviembre, by the new Law 3/2014 de 27 de marzo with the aim to transpose the Directive 2011/83/UE on electronic contracts with customers has changed many of the conditions in the procedures of a contract such as the right to inform the customer, their right to cancel the contract, and the duties of the seller to deliver.

Though the aim of the Directive is the harmonization of the digital market, it does not seem that there will be an increase in contracting through the Internet, neither at the national nor at the international levels. We believe that this still depends more on sociological or psychological factors rather than on the regulatory framework.

Competitiveness, privacy and customer protection as pillars of the European common digital market.

Ramon Miralles, Coordinador de Auditoria y Seguridad de la Información. Autoridad Catalana de Protección de Datos.

If Europe needed a unique market, it was time to act and to have a roadmap. That was the idea behind the Digital Agenda for Europe.

Privacy and, especially, trust in the system were top priorities.

One of the problems of Europe is that it reacts very slowly.

It seems that the new trends in e-commerce will be determined by privacy and trust. Data protection, consumer protection and competition could be the core policies in e-commerce in Europe.

News in the right to information of the customer in electronic contracts

María Arias Pou. Directora de ARIAS POU Abogados TIC. Coordinadora de la Comisión de Menores de APEP. Profesora de Derecho de las Nuevas Tecnologías de la Universidad Europea de Madrid.

The new Directive on the rights of the customers implies some changes in the right to information of the customer in electronic contracts. Changes that, at their time, change again along the whole process of transposition to the Spanish regulatory framework.

The problem is that the regulation that applies is disperse, with three scenarios: a contract with a customer, at a distance, online. This mess actually challenges the principle of ‘minimum information’, which becomes worse when it has to be accessed through mobile devices during the process of informing the customer.

Electronic commerce plays nowadays a crucially important role in both professional and private activity of European consumers and businesses. The precontractual information duties are one of the factors that distinguish online contract formation between businesses and consumers from other ways of selling goods and services. The rules that apply to the e-commerce in the scope of the European internal market originate in two different legal systems, that is in the European law and in the national law. The aim of this study is to analyse and compare remedies available to consumers in the case of breach of information duties by the trader. The traditional contract law of Spain and England offers various remedies for not providing the other party with the due information. The interest in comparing those legal systems lies in the possible high number of cross-boarder transactions and the different nature of common and continental law. Even though the European legislation imposes numerous information duties, usually the remedies available for breach of those duties are left to the Member States’ internal law, and therefore the analysis of the remedies available in the internal national law results necessary. The remedies that will be analysed and compared in this study are, under English law, misrepresentation, fraudulent, negligent or innocent, mistake, breach of statutory duty and breach of contract, and in what refers to Spanish law, remedies for vices of consent, for culpa in contrahendo, and for breach of contract.

How do we protect customers in the so-called Internet of Things? Is our regulatory framework prepared for the Internet of Things?

The Internet of Things will challenge matters of privacy, or (technological and personal) security. An imbalance in how we solve these challenges may incur in power imbalances. There is a growing risk of firms can take advantage of some procedures to abuse the customer.

The Internet of Things presents three main scenarios of added value: sensors, apps and cloud computing services. Depending on where business happens, regulation will necessarily have to adopt.

We need codes of behaviour and governance for application platforms.

10th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 July 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: idp, idp2014, julian_valero

No Comments »

Chairs: Agustí Cerrillo, Professor, School of Law and Political Science (UOC).

Julián Valero. Professor of Administrative Law at the University of Murcia (Spain).

From digitalization to technological innovation: A juridical assessment of the modernization process of Public Administrations in the last decade

From digitization to technological innovation. The good thing about ICTs is especially the innovation they can bring with them into governments.

Is open government, open data, transparency a hype? Or is it a true believe in how things can be made different (and better)? It seems that the paradigm of accessing a document to be able to begin a procedure is over, that the government is already beyond that stage.

But many times it is not so: the government still creates laws (like the Spanish Law of Transparency) for the past, where the paradigm still is the standard procedure but digitized. With no improvement. We regulate access to documents, when citizens ask for access to data.

The theory is that we’re heading towards a smart government that provides services on demand. But it is a real practice only in very few cases.

The intensive use of technology has implied the appearance of new intermediaries between the administration and the citizen: technological intermediaries. And this appearance of new intermediaries often have an impact with legal issues. E.g. if I cannot access public information due to technological questions, who is liable for not respecting my right to information?

To be able to provide a 24×7 service, the administration now “lives in the cloud”… with all the strings attached to this decision: where are the citizen data, whose are those data, how to enforce the law or the service, etc.

And these problems get even worse when we speak about smart cities and big data.

We need technical norms as a guarantee of the juridical norms. We need technical knowledge to be able to design and enforce the best laws.

If we believe that ICTs can improve efficiency, we need to automate some procedures. Get rid of the human that is only clicking ‘next’ ‘next’ ‘next’ and adding no value

. This is a major challenge for public law, but one that needs being addressed. And being addressed from the start, when we are designing the technological tools. Regulatory frameworks and technological deployments should evolve in parallel.

We have to tell content from container. What matters is not the container, but content; what matters is not the document, but data. And this content has to be accessed with the independence of the container: we need open linked data.

Challenges?

We have to reset our legal guaranties. To assert our rights. To simplify procedures… or just get rid of the concept of “administrative procedure”… or to create ad-hoc and on-time procedures.

Discussion

Nacho Alamillo: the lobbies of the industry are setting up de facto standards (which often become de iure standards) but there are no representatives of the citizenry in the agoras where the lobbies meet. What should we do about that? Julián Valero: this is a very wicked issue. Yes, the citizens should participate in these debates, but we do not how. To regulate the participation in these agoras would not be enforceable or realistic. Maybe focusing on where the norm is applied (e.g. contracting some technologies) would be a better approach.

10th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 July 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: data_protection, idp, idp2014, privacy, yves_poullet

No Comments »

Chairs: Mònica Vilasau, Lecturer, School of Law and Political Science (UOC).

Yves Poullet. Rector of the University of Namur (Belgium). Professor at the Faculty of Law at the University of Namur (UNamur) and Liège (Ulg).

A new Privacy age: towards a citizen’s empowerment: New issues and new challenges

Changes in the technological landscape

Characteristics of the new information systems, between Tera and Nano. More ability to store speech, data, images. Increasing capacity as regards the transmission. Increasing capacity as regards the processing. increasing capacity as regards the storage capacity. On the other end, multiplication of terminal devices which are now ubiquitous (GPS, RFID, mobiles, human implants…).

New applications. New ways to collect data, especially through web 2.0 platforms (social networking sites, online services…) and ambient intelligence (RFID, bodies’ implants…). And new ways of data storage, such as cloud computing.

We have to acknowledge that we increasingly have less control and even ownership of our own data, which “live in the cloud”. And, indeed, neither we know where data is, in what territory, and which laws affect them.

New methods of data processing. Profiling, a method using three steps: data warehouse, data mining, profiling of individuals. Neuroelectronics, which is the possibility to modify the functioning of our brain (through body implants and brain computer interfaces, e.g. to stimulate the memory function or to reduce stress). Affective computing, on how to interpret feelings (e.g. facial movements) and to adapt the environment or to take decisions on the basis of that interpretation.

New actors. Stantardisation of terminals of communication, protocols, led by private organizations (IETF, W3C) and not by public/international ones. New emerging actors, such as the terminals’ producers, which lack regulation upon their behaviour, without “technology control”. New gatekeepers. Blurring of borders and, with them, blurring of states’ sovereignty.

The legal answer: privacy or/and data protection

Initially, privacy was understood as a right to opacity, the right to be left alone. Progressively data protection as a new constitutional right besides privacy, a way of re-establishing a certain equilibrium between the informational powers, a right to self determination, to control the flows of one’s informational image.

Three principles:

- Legitimacy of the processing.

- Right to a transparent processing for the data subject.

- Data protection authority (a new actor) as a balance keeper.

There is a trend of understanding privacy with the negative approach without reference to the large ‘privacy’ concept. We need to reassess the value of data protection today. We need to accurately manage the delicate balance between the need for intermitent retreat from others and the need for interaction and cooperation with others (cf. Arendt), now that there is a pervasive Lacanian “extimacy” due to social networking sites.

New privacy risks:

- Opacity, and the risks of anticipatory conformism.

- Decontextualization, data collected in one context might be used in another context.

- Reductionism, from individual to her data and finally to her profile by using data related to other people.

- Increasing assymmetry, between the informational powers of, from one part, the data subject and, from the other part, the data controller.

- Towards a suveillance society.

- Abolition of some rights.

The human facing ICTs: a man traced and surveyed, a man “without masks”, a reduced man, a man normalized. Where it is question of dignity, of individual self-determination, of social justice and… definitively democracy. Privacy — which is much more than data protection — should be seen as self-development.

New rights of the data subject: right to be forgotten, right to data portability.

10th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2014)

By Ismael Peña-López (@ictlogist), 04 July 2014

Main categories: Cyberlaw, governance, rights, e-Government, e-Administration, Politics, Information Society, Meetings, Participation, Engagement, Use, Activism

Other tags: henrik_kaspersen, idp, idp2014

No Comments »

Chairs: Maria José Pifarré, Lecturer, School of Law and Political Science (UOC).

Henrik Kaspersen, in active life holder of the Computer Law Chair of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Cybercrime: a decade of transformations

A definition of computer cribe by Donn Parker (1974):

- The computer system is the target.

- The computer system is the instrument.

- The computer system is the environment.

- The computer system is legitimation.

Computer crime evolves in parallel, in the level of crime and complexity, with the development of ICTs. And as crime increased and became more complex, so did international definitions, recommendations and adoption of measures to fight computer crime and to prevent it.

There is much cybercrime that actually is not such, as the involvement of communications in crime does not always mean that it is cybercrime properly speaking. So, we need to (re)define well cybercrime, state the different types of cybercrime, avoid duplication of domestic law, avoid specification and focus instead only on main conduct, etc.

Types of cybercrime:

- Technical crimes: threat of ICT-security and integrity (cracking, phishing, etc.).

- Fraud by means of ICT or by manipulation of ICT (forgery, embezzlement, identity theft, etc.)

- Content related offences: crimes that seem to be particularly facilitated by ICT (child abuse images, racist and xenophobe expressions, etc.); crimes that are likely not to be criminalized in most countries.

There has been an increasing co-operation at the international level to prevent and fight cybercrime. EU co-funded projects: Cyber@IPA for the Balkans and Turkey; Cyber@EAP for Eastern Europe; Glacy, with a worldwide approach.

The cybercrime convention of 2001 tries to bring together as much countries as possible to collaborate on the fight against cybercrime, as it is committed anywhere, and you can suffer it also anywhere. Support programmes: legal training, exchange of data, technical knowledge, co-operation with third parties (industry, ISPs).

Challenges of the fight against cybercrime:

- Lack of criminal statistics.

- Analysis by victim-reports.

- Emphasis on modus operandi.

- Technical offences today are only instrument for common crime.

- Specific perpetrator behaviour?

Discussion

Ismael Peña-López: could it be possible to include in these international agreements something on the public sector, on governments and their behaviours against Internet-related freedoms? Kaspersen: that is a very difficult issue. Could be a good idea, but for instance it is very difficult to tell if a country digitally boycotts another country’s firms or infrastructures, whether this is cybercrime, or cyber warfare, and what consequences should arise from that. Cybercrime will most likely remain within the boundaries of criminal law.

10th Internet, Law and Politics Conference (2014)